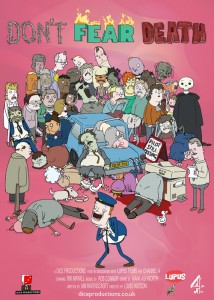

“Carpe Mortem”…. reads the title of this post. It is certainly not a popular or well-received saying for that matter. The phrase definitely has its share of negative connotations, and this past week I stumbled upon an interesting comedy clip, Don’t Fear Death, that defies the typical responses to mortality and instead glorifies the concept of death!

Courtesy of Dice Productions, this twisted humor features a male narrator who boasts of the benefits of dying. The narrator claims that with death comes freedom and the lack of responsibility. His obsession with death essentially implies that the fear of death is irrational. Although he aims to present his views in a positive light, the video clip is riddled with dark imagery, which does not necessarily seem like a strategic way of convincing audiences that death is as glorious and advantageous as the narrator perceives it to be. Every scene displays human corpses, bodily fluids, and there are also multiple appearances from Grim Reaper. However, this is an animated clip, so this imagery somewhat adds to the underlying humor of the overall story. It also decreases the affect that the concept of death and this perceived glorification may have truly had on general audiences if, say instead, real humans had been cast to portray the narrative.

At one point during the clip, the narrator questions our innate fear of death, and then proceeds to answer. Humans are “wary of that bright light and scared of the unknown.” Yes. This is certainly true considering the fact that generally as a culture, death is inevitably stigmatized and talk of it can be unsettling. That being said, humans are instinctively apprehensive of what awaits them: the nature of the death process, what it does to our bodies, how it affects the survivors, as we talked about in class, and how we, as a society, perceive death from that moment forward. Humans do not have control over such a phenomenon, which, in turn, can be frightening.

The end of the clip is comical and features an unexpected twist. The viewers discover that the male voice is that of a flight attendant on a plane, full of passengers, and that the plane has actually caught on fire. When the flight attendant concludes his unusual and for all intensive purposes, disturbing banter about the wonders of death, he is met with a silent and disapproving reaction from the passengers, who are also distraught about their life-threatening situation. Frustrated, the flight attendant takes the last available parachute, and he himself escapes death and lands safely, leaving the poor passengers destitute.

I am completely certain that the flight attendant is in denial of death. It is amusing that the he had never experienced death, but interestingly enough felt it necessary to speak so highly of the concept of death. Perhaps a logical explanation for his behavior was that he was unsure of how to confront the issue of death that soon awaited him. Maybe he wanted to convince himself to accept his fate, something he probably still feared even though he claimed otherwise. The fact that he selfishly left the passengers and escaped contradicts his entire argument that death is not the curse it once was. I believe that the writer chose to end the clip this way to reinforce this idea of mocking the public’s fear of and reactions to death. In all, the social implications of death, as illustrated by the flight passengers and ironically the actions of the attendant himself, demonstrate that culturally, there is much discomfort when dealing with and engaging in discourse concerning death.

View the clip here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wZHR5RqKw-0