Equality.

A term flaunted in many public circles, political campaigns, and social justice movements. In these instances, “equality” refers to fairness and justice in life; the act of viewing all people without bias or discrimination. Our society is obsessed with rallying behind crusades that foster impartiality in every aspect of life…but what about death? Is there equality in dying?

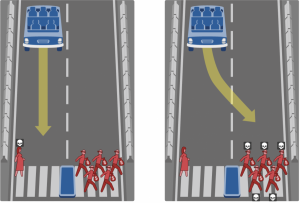

With current advancements in artificial intelligence, it is no surprise that self driving cars are on the horizon. In an effort to gather information about how humans make decisions, researchers at MIT created the “Moral Machine.” This database contains a variety of what-would-you-do scenarios involving car crashes and vehicular manslaughter in attempt to create an algorithm for decision making based on how humans act in life-and-death situations. For example:

This scenario incites intense debate over what the car should or should not do. If the car continues in a straight path, one woman and her unborn child will die. However, if the car is programmed to swerve, five people will die. If only provided with the number of deaths, many people would choose to have the car continue straight, saving the most lives. But what happens when we place value on those lives? When the victims are women and children, versus criminals, how do we decide which lives to value more and which deaths to value less? That is the heart of what the Moral Machine aims to uncover. By categorizing people into different groups based on their social value, we assign significance to individual deaths. After perceiving the criminals’ role in society, many people may change their minds and program the car to swerve, taking a greater number of lives but saving (arguably) more important or worthy ones.

The dilemma in the various circumstances boils down to the modern perception of death and the processes to follow. Our society has cultivated an environment that fights against death. People do not want to die “before their time” and thus are bred to accept death only when they feel that their life is complete or that they have nothing more to give. These personal sentiments are subconsciously broadcast into situations like the self-driving car, where knowing the demographics of a person ranks them on a scale ranging between “worth-saving-at-any-cost” to “not-a-huge-loss.” It sounds gruesome but it’s true.

Additionally, our determination of what the car should do originates in the process after a death. We can justify the decision to kill the five criminals if we consider that the pregnant woman and baby would be heavily mourned and grieved whereas the convicts probably would not.

Inadvertently, we place values on life and death based on our culture’s view of death and the proceedings to follow. Death and life seem to have an linear relationship; the more we value someone’s life the more we value their death. Is this a true embodiment of equality though? Can equality be extended to the grave? And lastly, what would you do?

To see other related scenarios, click here.

References

I found this article “When Doctors Grieve” that was published in the New York Times last May very interesting because it is a topic that isn’t discussed often and because I am an aspiring doctor. A study was done on twenty oncologists concerning grief practices when one of their patients died. Over half of them reported feelings of “self doubt, sadness, and powerlessness”. Many added that they felt guilty and would often cry and lose sleep. However, most of these oncologists fought to hide their emotions because it is seen as a sign of weakness as a medical professional. Surprisingly, the death of a patient oftentimes effects the behavior of the doctor and the treatment practices they perform on the patient. One doctor stated “I see an inability sometimes to stop treatment when treatment should be stopped.” This results in more aggressive chemotherapy treatments. Another aspect of this article which was of most interest to me was the idea that as a patient gets closer to dying, the doctor tends to distance themselves from the patient and their families resulting in an overall less effort toward the patient. I think this is because the doctor does not want to become too attached with the patient and develop a relationship with them because when they die, the doctor becomes affected by this both emotionally and professionally. The author of the article believes that doctors should be trained to handle their own grief and I agree. A great doctor is one that can compose themselves and carry on with their life while coping with the loss of their patient.

I found this article “When Doctors Grieve” that was published in the New York Times last May very interesting because it is a topic that isn’t discussed often and because I am an aspiring doctor. A study was done on twenty oncologists concerning grief practices when one of their patients died. Over half of them reported feelings of “self doubt, sadness, and powerlessness”. Many added that they felt guilty and would often cry and lose sleep. However, most of these oncologists fought to hide their emotions because it is seen as a sign of weakness as a medical professional. Surprisingly, the death of a patient oftentimes effects the behavior of the doctor and the treatment practices they perform on the patient. One doctor stated “I see an inability sometimes to stop treatment when treatment should be stopped.” This results in more aggressive chemotherapy treatments. Another aspect of this article which was of most interest to me was the idea that as a patient gets closer to dying, the doctor tends to distance themselves from the patient and their families resulting in an overall less effort toward the patient. I think this is because the doctor does not want to become too attached with the patient and develop a relationship with them because when they die, the doctor becomes affected by this both emotionally and professionally. The author of the article believes that doctors should be trained to handle their own grief and I agree. A great doctor is one that can compose themselves and carry on with their life while coping with the loss of their patient.