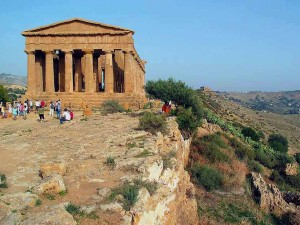

This summer I studied abroad in Italy, and in six weeks, I traveled to over 40 cities. We didn’t have a traditional classroom setting for the streets of Rome, the museums of Pisa, the temple of Agrigento (in Sicily), and even the seats of our bus, winding through the Tuscan hills, served as our classroom.

One of the two courses we took was called Medicine and Compassion, and our professors were from the CDC and Emory Medical School. I thought our professor must be “science people” and we would just talk about medicine because what could you teach about compassion other than to have it?

Looking back, I laugh at my former self for my naivety. In this class, we read a few books, several short stories, and many articles that highlight compassion, empathy, communication, and ethical dilemmas. We were constantly asked, “what is compassion?” I began in Rome thinking compassion was feeling bad and being nice to a person who was dealing with a difficult thing and trying to put myself in their shoes. Wait isn’t that empathy thought? I was very confused and continued to be. My definition changed weekly with new insight gained and old preconceived notions lost. By the end of the program, my definition of compassion included the ability to connect at a personal level despite not having been in their situation and being able to communicate with them so that they could understand me and I could understand them.

You may think, “What does compassion have to do with informed consent?” Don’t worry; I’m getting there! Informed consent relies on physicians educating their patients and explaining what is wrong with them, the risk of a procedure, or their prognosis. In the article “Should informed consent be based on rational beliefs?” the author states “physicians duties as educators are more extensive … physicians must be prepared to do more than provided patients with information relevant to making evaluative choices. They must attend to how that information is received, understood, and used”.

I used to, and I am sure many physician still today, believe that you just need to tell the patients the facts. What could be so hard to understand? It is very easy for people to forget that not everyone knows or comprehends their field, and this is particularly true in medicine. Furthermore, physicians and other professionals alike are at the top tier of the education spectrum and there are many patients who did not go to college or even graduate high school. Those patients ability to understand medical terminology and the implications of treatments is much more limited. Thus, it requires the physician to have compassion and educate the patients to obtain true and complete informed consent.

Below is a link to an article in the New York Times called “Can Doctors Be Taught How to Talk to Patients?” I think this article, like my study abroad program, demonstrates the medical communities recognition and refocusing on the doctor-patient relationship and what exactly that should entail. According to the NY Times article “after all, [doctors] admission to medical school was not based on a validated assessment of their ability to relate to other human beings.”

References:

Savulescu, Julian. and Momeyer, Richard. “Should informed consent be based on rational beliefs?” Arguing About Bioethics. Ed. Stephen Holland. London: Routledge, 2012. 332. Print.

I really like some of your points and do not believe true compassion can be taught. True compassion is an innate characteristic; some people have it and others do not. As stated, many physicians are incredibly intelligent academically but have minimal communication skills, since that is not a requirement for medical school. Even if one is not naturally compassionate a form of compassion can be taught, however it might be feel forced or not genuine. Being able to sympathize with a patient and communicate at their level is all compassion (real or forced) consists of and all physicians should be able to do this in order to provide their patient with a caring and helpful environment. This leads into the idea that informed consent cannot be provided without compassion, and I completely agree. If a physician is unable to communicate at the patient’s level, then who knows what the patient is truly comprehending? If a patient is agreeing to something vague or unclear to them due to the physician’s lack of clarification on their level, then informed consent was never attained. Overall I believe that physician’s need to either use their innate compassion skills (if they have them) or learn to work compassionately even if forced, in order to provide the patient with both understandable information and a caring environment.

I agree that many doctors are not adequately connecting with the patients and ensuring that they understand what is being done to them. Unfortunately, patients will never fully understand due to the educational gap between patients and physicians. However, patients can be made to comprehend the gist of the treatment. You are right in the fact that matriculation into medical school may not require interpersonal skills; however, I sense that this will gradually change. In fact, after this year the MCAT is going to include testing of social sciences, and medical school interviews are now evaluating how candidates interact with others in team interviews as well as the interviewers themselves. As the medical field is rapidly changing, many people are realizing the importance of interpersonal skills in a doctor. During a medical program I attended over the summer, many of our activities centered around building rapport with patients and developing interpersonal skills. Moreover, patients are starting to realize that they would rather have a personable doctor; hence, an impersonable doctor will begin to lose patients and money. This should help motivate doctors to work on their relationship with the patient. Otherwise, they won’t have a job!

Your thoughts on the necessity of relaying information to patients in a way that they can understand are interesting. I agree with you, I think there is a sometimes an overwhelming disconnect in what a doctor is saying and how the patient is interpreting it. I think that in some cases, doctors overestimate a patient’s medical literacy, and as a result they do not express things clearly enough. We talked a little bit in class a few weeks ago about the fact that doctors need to assess their patients on a case by case basis in order to determine the manor in which to speak to them, balancing their intent not to insult their patient’s intelligence but also making sure that the patient is well informed.

While doing research for my paper I came across studies about the complaints patients had with regards to the events of medical errors. They did not think that doctors communicated (disclosed) information in a sufficient way. Often, patients were left to “connect-the-dots”. I think this is applicable across the field and is definitely something to be improved upon in the health care system.

I think what you said really points out one of the main issues that still remain in informed consent. I believe that doctors, but more importantly, those who control what doctors do can actually need to make the changes required to help improve physician-patient communication. I believe that it is rather difficult to make the changes required and necessary to increase the amount of patient-physician contact. If physicians are forced to see a myriad of patients in a short time span, they are not able to describe details and such to patients. Informed consent could work so much better if the doctor had time to explain treatments and procedures to patients, allow the patient to take some time to think and find any questions they have, and then time to also go over the procedure again. However, it is difficult for physicians to do this.

And it is not that they are not compassionate, they just don’t have the time. Thus as Savulescu and Momeyer state, they do not have the relevant information necessary to rationally deliberate what options are best for their health.

I think there is definitely a gap between doctors and patients where the two have a difficult time connecting with each other. However, I don’t think it’s the physician’s fault for the lack of compassionate. Physicians and patients are not the only people involved in the medical system. The system is very complicated and sometimes physicians do not have a say in what they do. There can be compassionate physicians but it’s just that the system doesn’t allow them to take the time to get to know their patients. Also, it’s not just how the hospital system is set up but also how medical schools are set up. Right now, we have a system in which physicians are forced to be on a certain level with their patient. These physicians serve as role models for medical school students and residents. They learn from the physicians and thus, the practice gets passed down. This cycle continues because the way of practice gets passed down from physician to physcian and the hospital system doesn’t make it any better. Students go into medical school because they want to help people but they end up getting sucked into the system. Perhaps we should think about how the system can be improved to encourage good physician-patient relationships.

I really enjoyed reading your post because I think the idea of compassion is very personal. Compassion isn’t something that you can really teach. I think it’s something that someone learns through his or her own experiences.

Unfortunately, the medical system is designed so that it’s very unlikely that the doctor and patient build a personal relationship. Therefore, it becomes very difficult for the physician to have compassion for his or her patient because they probably don’t understand each other. The physician would be able to feel compassion for his or her patient if this personal relationship was built and there was clear communication between the two of them. Without knowing any personal information about the other, or not being able to connect personally at all, compassion won’t be possible.

Again, compassion is something that you feel when you can connect with someone on more than just a doctor-patient relationship level. Therefore, the doctor and patient need their relationship to be more personal in order for the physician to be compassionate for the patient.

To go off of how the system can be improved, I really think it’s about the physician keeping the right mindset and perspective throughout his or her career. The best way to change the system is from the inside out, through patient-physician relationships built on trust and compassion. It takes a special type of person to acknowledge the obstacles in the way of a healthy relationship (less time to physically see a patient or cognitive gaps between the two), to assess potential ways to go about things, and to ACT upon these decisions in a professional and thorough manner. Just because physicians don’t have as much time as they would like does not mean that they aren’t compassionate. The same goes for physicians who are meeting a patient for the first time. If the physician is good at his or her job and is a compassionate individual they will take the time to get to know you and do their best in providing treatment options. Some of my favorite doctors have been the ones that make me feel like I have had a relationship with them for a long time, despite only recently meeting them. They had the ability to connect with me on a personal level and put indifferences aside. I think that is compassion in its truest form. Doctors like that improve the system.

The complexity of the human body should never be underestimated. Doctors may know a lot, after so many years of immersive studying, but even they do not know everything. How is everyone else expected to be able to understand the information they are getting in a way that will actually be beneficial to their health? This is why I like the definition of compassion you ended up with at the end of your trip,” the ability to connect at a personal level despite not having been in their situation and being able to communicate with them so that they could understand me and I could understand them.” This highlights most importantly the essential factor of communication in the relationship, which is driven by compassion via informed consent as a tool!

I really appreciated how you showed the development of your definition of compassion as time progressed and you became more knowledgeable about the subject. The idea of compassion playing a key role seems to be very elementary and basic, but rather is something that has recently been gaining more attention rapidly. With the entering of 2015, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) will be releasing a new version of the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT). This new version will also focus on “the importance of socio-cultural and behavioral determinants” in addition to original natural sciences content. This, I believe, functions to cause aspiring medical students, the future doctors, to be more aware of qualities that a doctor should have in addition to the medical knowledge they possess, like basic bed side manner and the ability to communicate and articulate based off of the background of the patient.

https://www.aamc.org/students/applying/mcat/mcat2015/

It is interesting that you brought up “compassion.” It is true that patients and doctors might have gap when communicating about the medical facts due to the levels of education. In order to bring the gap closer, compassion plays an important role. Today, not a lot of doctors show compassion; this might due to the education and health care system. Doctors of course know a lot of knowledge, but do they necessary know how to communicate with patients by understanding them and making the patients understand the doctors? The problem here is how can doctors have compassion. There was a research from the University of Wisconsin that compassion can be trained. Personally, in order to have better quality doctors, I believe that in medical school, there should be a course that teach the students about compassion and how to deal with patients. Without doctors having compassion, patients might not be able to fully understand the whole situation.

I think it’s very important for doctor’s to have the skills to interact compassionately with people. For some people, this is a natural thing that does not need to be taught, but for others it’s very difficult and needs to be objectively be taught to them. I don’t know much about med school curriculums, but I would hope students would have these sorts of classes.

I find this similar to teachers and the ability to teach. There’s a big difference between possessing the knowledge that needs to be relayed and being able to effectively relay it. I know we’ve all had those teachers where we know they’re very smart, but they just suck at teaching. They don’t know how to work with people, say things in a way that is easy to understand or have the patience to assist those who don’t automatically get things.

Just because you have the desire to do something (be a doctor, teacher, etc.) does not mean you have the ability to do so effectively, and the skills need to be taught. I agree that having compassion and exercising it are important skills for a doctor to possess and although we might like to think that everyone inherently knows how to be compassionate, they don’t.

This is a good tip especially to those fresh

to the blogosphere. Simple but very accurate info?

Many thanks for sharing this one. A must read article!

Regards for this post, I am a big fan of this website would like to go along updated.