In Holm’s article “Obesity Interventions and Ethics” he discusses whether or not it is appropriate to have public health policies that intervene to promote a person’s health. In this essay, Holm’s focuses on obesity interventions as the public health issue. Holm states that there are two main problems with this are when and if it is actually justifiable to have such policies that intervene in order to promote someone’s health and if it justifiable to have policies that can negatively affect people but benefits the common good.

Public health policies always have a paternalistic side to them, it’s just a matter of how much paternalism a policy wants to utilize. Holm’s defines three different forms of paternalism including hard paternalism, soft paternalism and maternalism (392). All three forms use different methods, to achieve a certain end. Soft paternalism, which includes “providing unwanted information or foreclosing some options for action”, should be utilized in public health policy (Holm, 392). In this way a specific decision is not forced onto a person, however they are given the information to make better (and maybe easier) decisions about maintaining their health. Some of these policies include changing food labels and changing advertising methods.

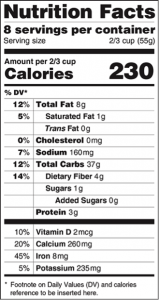

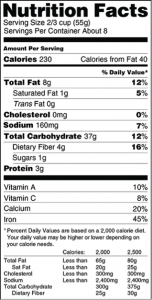

Recently the FDA has suggested new changes to food labels in order “to bring attention to calories and serving sizes” which are important in addressing problems related to obesity. Changes include writing calories in a larger font, adjusting amount per serving, and updating the necessary daily values for various nutrients and vitamins (United States). Here is a picture of the differences between our current food labels (right) and the suggested future one (left).

The main goal of these changes is to “make people aware of what they are eating and give them the tools to make healthy dietary choices throughout the day” (United States). Changing food labels will just help people become more aware of what they are eating. Even though the label may be providing “unwanted information” people can still choose to disregard the information therefore it would benefit the common good without negatively affecting people (392).

Chile has also recently changed their food labels to be more representative of the foods contents. The Law of Food Labeling and Advertising was passed in July 2012 and focuses on regulating and labeling critical nutrients, adding warning messages to foods and reducing the amount of food marketing toward children (Corvalán, Reyes, Garmendia, Uauy, 2013). Chile is still surveying their new changes and augmenting them, however the ideas that they suggested fall under soft paternalism. If the policies prove successful, they could be utilized in United States obesity prevention efforts.

Children are group that is often referenced in paternalism debates. The same is true in regards to obesity prevention. Children are bombarded with food advertisements while watching television, which can increase their consumption of such foods. Andreyeva found that “Exposure to 100 incremental TV ads for sugar-sweetened carbonated soft drinks during 2002–2004 was associated with a 9.4% rise in children’s consumption of soft drinks in 2004. The same increase in exposure to fast food advertising was associated with a 1.1% rise in children’s consumption of fast food” (2011). The increased associated risk may seem small, but you have to think about the number of children that it is affecting and the long-term effects of this exposure. A 2008 study found that the amount of fat on a child directly increased with fast food advertising exposure (Andreyeva, Kelly, Harris, 2011). The same study suggests that reducing the amount of exposure could reduce adiposity by 18% (Andreyeva, Kelly, Harris, 2011The evidence provided suggests that merely reducing the amount of fast food commercials directed at kids could help maintain their current and future health.

All of the solutions that I have suggested have scientific evidence behind it, and have been implemented. The policies also maintain their paternalistic roots allowing no negative consequences to be forced on anyone but simultaneously is improving the health of the general public.

Sources:

Andreyeva, T., Kelly, I.R., Harris, & J.L. (2011). Exposure to food advertising on television: Associations with children’s fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Elsevier, 9(30): 221-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2011.02.004

Coravalán, C., Reyes, M., Garmendia, M.L., & Uauy, R. (2013). Structural responses to the obesity and non-communicable diseases epidemic: the Law of Food Labeling and Advertising. Obesity Reviews, 14(2): 79-87. Doi: 10.1111/obr.12099.

Holm,S. Arguing about Bioethics. Ed. Stephen Holland. Routledge: New York, NY, 2012. Print.

United States. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Nutrition Facts Label: Proposed Changes Aim to Better Inform Food Choices. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm387114.htm#different.