The Ritual Promise: Safety at Sea

Literary, toponymic, and material evidence affirm that the great fame of the Samothracian rites was linked to the promise to keep travelers safe at sea. Literary evidence ranges from onstage jokes in fifth-century Athens to Hellenistic epigrams; toponymic evidence reflects the use of the island as a point to steer by for ancient sailors. Material evidence includes the monumental and the personal: the cultural pathways for affirming Samothracian protection over the sea were varied and multiple.

A. The Literary Evidence

- Aristophanes, Pax 276-86 (226)

- Scholia to Aristophanes, Pax, 277-78. (226a)

- Cicero, de Natura Deorum 3.37.89 (230)

- Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 6.2.59 (231)

- Theophrastus, Charakteres, 25.2 (227)

- Kallimachos, Anthologia Palatina, 6.301 [Epigrams, 48] (228)

- Automedon, Anthologia Palatina, 2.346.5-8 (228a)

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, 10.421d-e (238)

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 1.915-21 (229)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, 4.43.1-2 (229b)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, 4.48.5-7 (229c)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, 4.49.8 (229d)

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica, 2.431-42 (229e)

- [Orpheus], Argonautica, 467-72 (229f)

- Scholia Laurentiana to Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 1.917-18 (229g)

- Scholia Parisina to Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 1.917-18 (229h)

- Ovid, Tristia 1.10.45-50 (232)

- Anonymous Comoedia nova, fragment, (Greek Literary Papyri, LCL 1.61) (233)

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, 7.282e-283a (236)

- Aelian, de Natura Animalium, 15.23 (235/234)

- Herodotus, Histories, 3.37.2-3

- Lucian, Epigram 15 (Anthologia Palatina 6.164) (237)

B. A mountain to steer by: Toponyms and ancient descriptions

Toponyms are critical aids for maritime navigation in both ancient and contemporary contexts: they invest the landscape with names and narratives which humanize or divinize, offer mnemonic force, warn of dangerous passages and declare the affiliation of the region’s inhabitants (Morton 2001; Marangou and Della Casa 2008). Samothrace’s names reflect these functions: they emphasize visibility (‘moon mountain’ ‘shining one’ ‘white’ ‘high/lofty’ or even ‘saved’). Accounts of the place as a mountain from which visibility was extensive (see Poseidon on the peak, Tozer in his 19th c travels), and to which people threatened by the sea could flee (the flood myth), reinforce these.

Toponymns:

The passages with numbers below are from the scan ‘Samothrace texts origins legends’ – another selection from Lewis. There are a few I still need to chase down – but you can see that the names in question are Phengari, Leucosia/Leucania, Samos, Saos/Saii.

Phengari ‘Mountain of the Moon’

Leucosia, ‘white one’ – in Aristotle, de republ (#37)

Scholia Laurentiana to Apollonius Rhodius Argonautica 1.917a (#37)

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| ἡ δὲ Σαμοθρᾴκη ἐκαλεῖτο πρότερον Λευκοσία, ὡς ἱστορεῖ Ἀριστοτέλης ἐν Σαμοθρᾴκης πολιτείᾳ. ὑστερον δὲ ἀπὸ Σάου τοῦ Ἑρμοῦ καὶ Ῥήνης παιδὸς Σάμος προσωνομάσθη κατὰ παρένθεσιν τοῦ μ. Θρᾳκῶν δὲ οἰκησάντων αὐτὴν ἐκλήθη Σαμοθρᾴκη. | Samothrace was at an earlier period called Leucosia, as Aristotle recounts in his Constitution of Samothrace. Later, after Saos, son of Hermes and Rhene, it was further names Samos through the insertion of an m. Then, when Thracians settled in it, it was called Samothrace. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

Leucania, ‘white one’, anonymous geographer, #38

Anon, Geographica, (Madrid fragment quoted in FHG, II, 218 n.) (#38)

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| Λευκανία ἡ νῦν Σαμοθρᾴκη. | Leucania [used to be the same name of the island] now called Samothrace. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

Heraclides, Respublicae 21, (= FGrHist, 548 F 5b)

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| ἡ Σαμοθρᾴκη τὸ μὲν ἐξ ἀρξῆς ἐκαλεῖτο Λευκανία, διὰ τὸ λευκὴ εἶναι· ὓστερον δέ, Θρᾳκῶν κατασχόντων, Θρᾳκία. τούτων δὲ ἐκλιπόντων, ὓστερον ἔτεσιν ἑπτακοσίοις Σάμιοι κατῴκισαν αὐτὴν ἐκπεσόντες τῆς οἰκείας, καὶ Σαμοθρᾴκην ἐκάλεσαν. | Samothrace was originially called Leucania because of its being white (leuke), later Thracia, when Thracians occupied it. Seven hundred years after the latter had left it, Samians banished from their homeland settled in it, and called it Samothrace. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

‘Samos’ was the word for ‘high’ in local, non-Greek languages (Strabo 10.2.17, #42; Scholia Townleiana to Iliad 24.78, #45; Eustathius ‘Commentarii in Dionysii ‘Periegesin’ 533, GGM II 322, #39;

Strabo 10.2.17 (457c) (=FgrHist, 244 F 178 [Apollodorus], 545 F 5b, 548 F 5g) #42

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| καλεῖ δʹ ὁ ποιητὴς Σάμον καὶ τὴν Θρᾳκίαν, ἥ νῦν Σαμοθρᾴκην καλοῦμεν. τὴν δʹ Ἰωνικὴν οῖδε μέν, ὡς εἰκός· καὶ γὰρ τὴν Ἰωνικὴν ἀποικίαν εἰδέναι φαίνεται· οὐκ <ἂν> ἀντιδιέστειλε δὲ τὴν ὁμωνυμίαν, περὶ τῆς Σαμοθρᾴκης λέγων τότε μὲν τῴ ἐπιθέτῳ <<ὑφοῦ ἐπʹ ἀκροτάτης κορυφῆς Σάμου ὑληέσσης, Θρηικίης,>> τότε δὲ τῇ συζυγίᾳ τῶν πλησίον νήσων <<ἐς Σάμον ἔς τʹ Ἴμβρον καὶ Λῆμνον ἀμιχθαλοέσσαν,>> καὶ πάλιν <<μεσσηγύς τε Σάμοιο καὶ Ἴμβρου παιπαλοέσσης.>> ᾒδει μὲν οὖν, οὐκ ὠνόμακε δʹ αὐτήν… ἐπεὶ οὖν κατὰ τὰ Τρωικὰ Σάμος μὲν καὶ ἡ Κεφαλληνία ἐκαλεῖτο καὶ ἡ Σαμοθρᾴκη (οὐ γὰρ ἂν Ἑκάβη εἰσήγετο λέγουσα ὅτι τοὺς παῖδας αὐτῆς <<πέρνασχʹ, ὅν κε λάβοι, ἐς Σάμον ἔς τʹ Ἴμβρον>>), Ἰωνικὴ <δʹ> οὐκ ἀπῴκιστό πω, δῆλον ὅτι ἀπὸ τῶν προτέρων τινὸς τὴν ὁμωνυμίαν ἔσχεν· ἐξ ὧν χἁκεῖνο δῆλον, ὅτι παρὰ τὴν ἀρχαίαν ἱστορίαν ὃ λέγουσιν οἱ φήσαντες, μετὰ τὴν Ἰωνικὴν ἀποικίαν καὶ τὴν Τεμβροίωνος παρουσίαν ἀποίκους ἐλθεῖν ἐκ Σάμου καὶ ὀνομάσαι Σάμον τὴν Σαμοθρᾴκην, ὡς οἱ Σάμιοι τοῦτʹ ἐπλάσαντο δόξης χάριν. πιθανώτεροι δʹ εἰσὶν οἱ ἀπὸ τοῦ σάμους καλεῖσθαι τὰ ὕφη φήσαντες εὑρῆστἁι τοῦτο τοὔνομα τὴν νῆσον ἐντεῦθεν γὰρ <<ἐφαίνετο πᾶσα μὲν Ἴδη, φαίνετο δὲ Πριάμοιο πόλις καὶ νῆες Ἀχαιῶν.>> τινὲς δὲ Σάμον καλεῖσθαί πἁσιν ἀπὸ Σαίων, τῶν οἰκούντων Θρᾳκῶν πρότερον, οἳ καὶ τὴν ἤπειρον ἔσχον τὴν προσεχῆ. | The poet [Homer] also calls “Samos” the Thracian island which we call Samothrace. And he apparently knows the Ionian Samos, for he seems to know the Ionian migration, and he would not, otherwise, have bothered to distinguish the identity of name, designiating Samothrace now by an epithet, as in “high on the topmost summit of wooded Samos, the Thracian,” again by association with the neighboring islands, as in “to Samos and Imbros and inhospitable Lemnos,” or “betwixt Samos and craggy Imbros.” He knew the Ionian island, therefore, but did not name it… Since, then, both Cephallenia and Samothrace were called “Samos” at the time of the Trojan War (for otherwise Hecuba would not be introduced declaring that those of her children “whom he might capture [Achilles] would sell off in Samos and Imbros”) and since Ionian Samos had not yet been colonized, it is clear that the latter received the same name as one of the islands that had it earlier. Whence this too is clear, that what those writers say, who declare that after the Ionian migration and the arrival of Tembrion settlers came from Samos and names Samothrace Samos, is contrary to the history of antiquity, since the Samians made up this story to gain glory. More credible are those writers who say that the island received its name from the fact that heights were called “samoi,” for from them “all Ida was visible, and the city of Priam and the ships of the Achaeans.” But some say that it was called Samos after the Saii, the Thracians who dwelt in it previously and who held also the adjacent [part of the] mainland. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

Scholia Townleiana to Iliad 24.78 (=FGrHist, 548 F 5e)a #45

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| Σάμοιο τῆς νῦν Σαμοθρᾴκης. σάμους δὲ τοὺς λόφους ἔλεγον. ἐκαλεῖτο δὲ Λευκωνία· εἶτα ὑπὸ Σαμίων οἰκισθεῖσα, ὧν τὰ σκάφη αἰχμάλωτοι Θρῇσσαι (θρῆκαι cod.) κατέκαυσαν, Σαμοθρᾴκη ὠνόμασται. | Of Samos: present-day Samothrace. The hills were called “samoi.” The island was [originally] called Leuconia; then, settled by Samians whose boats were burned by captive Thracian women, it received the name of Samothrace. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

Eustathius Commentarii in Dionysii “Periegesin” 533 (GGM, II, 322) #39

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| ἰστέον δὲ ὅτι Ἰωνικὴν τὴν ῥηθεῖσαν Σάμον φαμέν, ὡς ἂν ἀντιδιαστέλλοιτο τῇ τε Ὁμηρικῇ Κεφαλληνικῇ Σάμῳ, τῇ προειρημένῃ δὲ Θρακίᾳ Σάμῳ, τῇ οὕτω κληθείσῃ διὰ τὸ ὕψος· σάμοι γάρ φασι τὰ ὕψη· ὅτι δὲ εἰς πολὺ ἐξήρετο ὕψος, δῆλον ἐκ τοῦ καὶ τὸν ποιητὴν εἰπεῖν ἐξ αὐτῆς τήν τε Ἴδην φαίνεσθαι πᾶσαν καὶ τὰ κατὰ τὴν Τροίαν. οἰ δέ φασιν ὅτι Σάμος λέγεται ἡ Θρᾳκία οἱονεὶ Σάος τις, καὶ κατὰ πλεονασμὸν τοῦ μ Σάμος, ἀπὸ Σαίων, ἔθνους παλαιοῦ οἰκήσαντος αὐτήν. | It should be understood that we call there here-mentioned Samos “Ionian” in order to distinguish it from the Cephallenian Samos of Homer and from the aforementioned Thracian Samos, so called from its height. For heights are called “samoi”; and that the island rose to a considerable height is clear from the poet’s [Homer’s] statement that from it could be seen all Ida and everything around Troy. But some say that the Thracian isle is called Samos as if for Saos with a pleonastic m, after the Saii, an ancient people which inhabited it. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

The claim that ‘Samos’ could become ‘Saos’

Scholia (Tzetzes) to Lycophron Alexandra 78a

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| <ΣΆΟΝ> Σάμον κατὰ συστολὴν τοῦ μ· Σάον ὄρος Σαμοθρᾴκης οὗ μέμνηται Νίκανδρος ἐν τοῖς Θηριακοῖς.b | Saon: Samos, through syncopation of the m. Saon is a mountain of Samothrace; Nicander mentions it in his Theriaca.b |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

Saos is also the son of Hermes for whom the island was named (#37); for the argument that the name ‘Saii’ could also articulate maritime safety, and that Greeks would hear in it the word ‘saved’, see Larson 2001: 178.

Visibility:

Poseidon (Iliad 13.10) Homer’s description of Poseidon sitting on the peak to watch the battle on the plains of Troy emphasizes the mountain’s potential for lookout as well as navigation (Iliad 24.77-84, 13.33, 13.10-14);

Homer, Illiad 13.10-18

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| οὐδ’ ἀλαοσκοπιὴν εἶχε κρείων ἐνοσίχθων· καὶ γὰρ ὁ θαυμάζων ἧστο πτόλεμόν τε μάχην τε ὑψοῦ ἐπ’ ἀκροτάτης κορυφῆς Σάμου ὑληέσσης Θρηικίης· ἒθεν γὰρ ἐφαίνετο πᾶασα μὲυ Ἴδη, φαίνετο δὲ Πριάμοιο πόλις καὶ νῆες Ἀχαιῶν· ἔνθ’ ἄρʹ ὅ γ’ ἐξ ἁλὸς ἕζετ’ ἰών, ἐλέαιρε δ’ Ἀχαιοὺς Τρωσὶν δαμναμένους, Διὶ δὲ κρατερῶς ἐνεμέσσα. αὐτίκα δ’ ἐξ ὄρεος κατεβήσετο παιπαλόεντος κραιπνὰ ποσὶ βιβάς. | But the lord, the shaker of the earth, kept no careless watch. Marveling at the warfare and the battle, he sat high on the topmost peak of wooded Thracian Samos, for thence all Ida was plainly seen, and plainly seen were the city of Priam and the ships of the Achaeans. Forth from the sea he came and there he sat, and he pitied the Achaeans, who were being overpowered by the Trojans, and he was sternly indignant at Zeus. Then down from the rugged mountain he went with swift strides. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

Tozer, traveling in 1890, saw from the mountain to Olympus in the east and Ida in the west (H.F. Tozer, The Islands of the Aegean (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1890)

Here, you get saved:

Diodorus Siculus 5.47: the mountain’s slopes provided refuge from those drowning in the sea when a great flood burst from the Bosporus

Diodorus Siculus 5.47.1-48.3 (=FGrHist, 548 F 1)

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| περὶ δὲ τῶν κατὰ τὴν Ἑλλάδα καὶ τὸ Αἰγαῖον μέλαγος κειμένων νῦν διέξιμεν, τὴν ἀρχὴν ἀπὸ τῆς Σαμοθρᾴκης ποιησάμενοι. ταύτην γὰρ τὴν νῆσον ἔνιοι μέν φασι τὸ παλαιὸν Σάμον ὀνομασθῆναι, τῆς δὲ νῦν Σάμου κτισθείσης διὰ τὴν ὁμωνυμ’αν ἀπὸ τῆς παρακειμένης τῇ παλαιᾷ Σάμῳ Θρᾴκης Σαμοθρᾴκην ὀνομασθῆναι. ᾢκησαν δʹ αὐτὴν αὐτόχθονες ἄνθρωποι· διὸ καὶ περὶ τῶν πρώτων γενομένων παρʹ αὐτοῖς ἀνθρώπων καὶ ἡγεμόνων οηηυδεὶς παραδέδοται λόγος. ἔνιοι δέ φασι τὸ παλαιὸν Σαόννησον καλουμένην διὰ τοὺς ἀποκτισθέντας ἔκ τε Σάμου καὶ Θρᾴκης Σαμοθρᾴκην ὀνομασθῆναι. ἐσχήκασι δὲ παλαιὰν ἰδίαν διάλεκτον οἱ αὐτόχθονες, ἧς πολλὰ ἐν ταῖς θυσίαις μέχρι τοῦ νῦν τηρεῖται. οἱ δὲ Σαμόθρᾳκες ἱστοροῦσι πρὸ τῶν παρὰ τοῖς ἄλλοις γενομένων κατακλυσμῶν ἕτερον ἐκεῖ μέγαν γενέσθαι, τὸ μὲν πρῶτον τοῦ περὶ τὰς Κυανέας στόματος ῥαγέντος, μετὰ δὲ ταῦτα τοῦ Ἑλλησπόντου, τὸ γὰρ ἐν τῷ Πόντῳ πέλαγος λίμνης ἔχον τάξιν μέχρι τοσούτου πεπληρῶσθαι διὰ τῶν εἰσρεόντων ποτάμων, μέχρι ὅτου διὰ τὸ πλῆθος παρεκχυθὲν τὸ ῥεῦμα λάβρως ἐξέπεσεν εἰς τὸν Ἑλλήσποντον καὶ πολλὴν μὲν τῆς Ἀσίας τῆς παρὰ Θάλατταν ἐπέκλυσεν, οὐκ ὀλίγην δὲ καὶ τῆς ἐπιπέδου γῆς ἐν τῇ Σαμοθρᾴκῃ θάλατταν ἐποίησε· καὶ διὰ τοῦτʹ ἐν τοῖς μεταγενεστέροις καιροῖς ἐνίους τῶν ἁλιέων ἀνεσπακέναι τοῖς δικτύοις λίτἱνα κιονόκραυα, ὡς καὶ πόλεων κατακεκλυσμένων. τοὺς ὑψηλοτέρους τῆς νήσου τόπους· τῆς δὲ θαλάττης ἀναβαινούσης ἀεὶ μᾶλλον, εὔξασθαι τοῖς θεοῖς τοῖς ἐγχωρίοις, καὶ διασωθέντας κύκλῳ περὶ ὅλην τὴν νῆσον ὅρους θέσθαι τῆς σκτηρίας, καὶ βωμούς ἱδρύσασθαι, ἐφʹ ὧν μέχρι τοῦ νῦν θύειν· ὥστʹ εἶναι φανεὸν ὅτι πρὸ τοῦ κατακλυσμοῦ κατῴκουν τὴν Σαμοθρᾴκην. μετὰ δὲ ταῦτα τῶν κατὰ τὴν νῆσον Σάωνα γενόμενον, ὡς μέν τινές φασιν, ἐκ Διὸς καὶ νύμφης, ὡς δέ τινες, ἐξ Ἕρμου καὶ Ῥήνης, συναγαγεῖν τοὺς λαοὺς σποράδην οἰκοῦντας, καὶ υόμους θέμενον αὐτὸν μὲν ἀπὸ τῆς νήσου Σάωνα κληθῆναι, τὸ δὲ πλῆθος εἰς πέντε φυλὰς διανείμαντα τῶν ἰδίων υἱῶν ἐπκνύμους αὐτὰς ποιῆσαι. οὕτω δʹ αὐτῶν πολιτευομένων λέγουσι παρʹ αὐτοῖς τοὺς ἐκ Διὸς καὶ μίας τῶν Ἀτλαντίδων Ἠλέκτρας γενέσθαι Δάρδανόν τε καὶ Ἰασίωνα και Ἁρμονίαν. ὧν τὸν μὲν Δάρδανον μεγαλεπὶβολον γενὸμενον, καὶ πρῶτον εἰς τὴν Ἀσίαν ἐπὶ σχεδίας διαπεραιωθέντα, τὸ μὲν πρῶτον κτίσαι Δάρδανον πόλιν. | We shall now give an account of the islands which lie in the neighborhood of Greece and in the Aegean Sea, beginning with Samothrace. This island, according to some, was called Samos in ancient times, but when the island now known as Samos came to be settled, because the names were the same, the ancient Samos came to be called Samothrace from the land of Thrace which lies opposite it. It was inhabited by men who were sprung from the soil itself; consequently no tradition has been handed down regarding who were the first men and leaders on the island. But some say that in ancient days it was called Saonnesus and that it received the name of Samothrace because of the settlers who emigrated to it from both Samos and Thrace. The autochthonous inhabitants used an ancient languages which was peculiar to them and of which many words are preserved to this day in the ritual of their sacrifices. And the Samothracians have a story that, before the floods which befell other peoples, a great one took place near them, in the course of which the outlet at the Cyanean Rocks was first rent asunder and then the Hellespont. For the Pontus, which had at the time the form of a lake, was so swollen by the rivers which flow into it, that, because of the great flood which had poured into it, its waters burst forth violently into the Hellespont and flooded a large part of the coast of Asia and made no small amount of the level part of the land of Samothrace into a sea; and this is the reason, we are told, why in later times fishermen have now and then brought up in their nets the stone capitals of columns, since even cities were covered by the inundation. The inhabitants who had been caught by the flood, the account continues, ran up to the higher regions of the island; and when the sea kept rising higher and higher, they prayed to the native gods; and since their lives were spared, to commemorate their rescue they set up boundary stones about the entire circuit of the island and established altars upon which they offer sacrifices even to the present day. For these reasons it is patent that they inhabited Samothrace before the flood.After the events we have described one of the inhabitants of the island, a certain Saon, who was a son, some say, of Zeus and a nymph, but, according to others, of Hermes and Rhene, gathered into one body the peoples who were dwelling in scattered habitations and established laws for them; and he was given the name Saon after the island, but the multitude of the people he distributed among five tribes which he named after his sons. And while the Samothracians were living under a government of this kind, they say that there were born in that land to Zeus and Electra, who was one of the Atlantids, Dardanus and Iasion and Harmonia. Of these children Dardanus, who was a man who entertained great designs and was the first to make his way across to Asia on a raft, founded at the outset a city called Dardanus. |

Source: Lewis, N. Ancient Literary Sources. Samothrace 1. New York: Pantheon, 1959.

C. Material and monumental evidence

The Neorion: A view of this building would have greeted visitors entering the sanctuary on Samothrace; it held an entire ship offered as a votive to the gods (Wescoat 2005)

Nike: The winged victory who loomed over the Samothracian site is perched on the prow of a ship (Knell 1997; Palagia 2010)

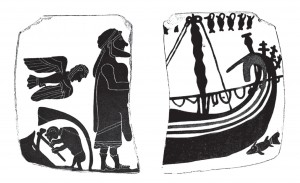

The Pinakes: Cicero de Natura Deorum 3.37.89 asked Diogoras of Melos if he had seen ‘tot tabulis pictis’ set up by men saved from disaster at sea; he responded, ‘It a fit, illi enim nusquam picti sunt, qui naufragia fecerunt in marique perierunt’ – cf. Diogenes Laertius 6.2.59, who reports Diogenes of Sinope’s reflection on the same question. For such pinakes, see Palmieri 2009. We do not have any of these preserved from Samothrace.

Pinax e. Palmieri, M.G. 2009. “Navi mitiche, artigiani e commerce sui pinakes corinzi da Penteskouphia: alcune riflessioni”, pp. 85-99 in F. Camia and S. Privitera, eds., Obeloi: contatti, scambi e valori nel Mediterraneo antico: studi offerti a Nicola Parise (Paestum). Figure 1.

Pinax b. Palmieri, M.G. 2009. “Navi mitiche, artigiani e commerce sui pinakes corinzi da Penteskouphia: alcune riflessioni”, pp. 85-99 in F. Camia and S. Privitera, eds., Obeloi: contatti, scambi e valori nel Mediterraneo antico: studi offerti a Nicola Parise (Paestum). Figure 2.