This summer, I learned to weave on a traditional loom in Santa Fe. I was celebrating the completion of tenure, and the irony was not lost on me: tenure is that academic marathon that demands maximum efficiency in research, teaching, and service productivity, and here I was choosing to learn a slow and inefficient craft. Each pass of the loom’s shuttle added just one line to the whole, building something substantial through countless small, patient actions. There could be no rushing, no shortcuts. Only the meditative attention to tension, color, and pattern, the gradual transformation of individual threads into something whole.

In a culture filled with optimization and measurable outcomes, I found joy in this slow creation—paralleling what Michael Suarez calls “slow knowing”—in a process that refuses acceleration, in work that honors human attention rather than the mechanical demands of productivity.

This same summer, I have been engaged in a different kind of weaving with Noe Martinez. Not with wool and cotton, but with words and memory, voice and silence, creating the fabric of a book through our own circuitous, sacred process.

Picture this: Noe on the phone while navigating a drive-thru during his lunch break, his voice alternating between ordering a sandwich and articulating the distinction between prison abolition and reform. I pace miles across the college quad, pausing mid-stride to take notes on what Noe is saying, trying to capture the precision of his thought before it dissolves into the afternoon air. We text paragraphs back and forth. These are fragments of ideas that refuse to wait for formal composition. We talk while both of us drive, voices weaving through traffic and across the distance between Chicago and Atlanta. He makes notes on a legal pad late at night, photographing them and texting them to me, I transcribe the notes into a Word document and copy them in a text them back to him. The next day, we test the words by reading aloud. “Not above,” Noe edits, “outside.” If I read a paragraph and he pauses before saying, “solid,” I know we landed it. If he pauses for several beats before asking a question, I know we have more editing to do.

Noe’s decade in prison and ongoing lack of digital resources made traditional academic collaboration impossible. So we developed our own methodology: alternately reading draft paragraphs aloud during two-hour phone conversations, editing each word as we speak, exchanging insights via text message during his work breaks, trusting our memories to hold complex ideas until they can be refined through dialogue. These limitations forced us into a more immediate, conversational form of co-authorship, where ideas had to be articulated clearly enough to survive transmission through voice and text, creating a different kind of intellectual communion than screen-based collaboration might allow.

Without access to productivity hacks, we may have stumbled into the most gloriously inefficient writing process imaginable, a methodology as deliberately slow and intentional as any traditional loom, as committed to honoring the organic rhythm of intellectual creation as my Santa Fe weaving teacher was to respecting the ancient wisdom of fiber and tension.

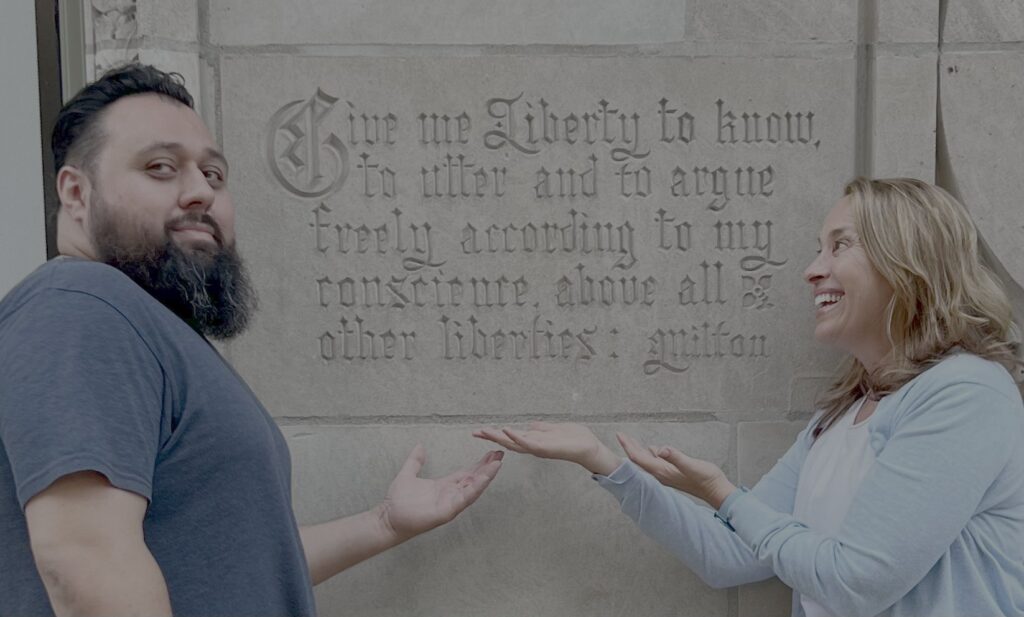

This is how Noe and I are writing a book for Routledge Press on critical prison theory and literature. Not buried in laptops, not tethered to productivity software, not dependent on tracked changes or shared Google Docs. We are speaking the book into existence, one conversation at a time, creating knowledge through the ancient and sacred technology of human voice meeting human voice across distance and constraints.

Noe and I first met in a college classroom inside prison eleven years ago. Our collaboration draws on that foundational experience: his lived understanding of how narratives and writing function within prisons, and my eighteen years of teaching literature and writing both inside and outside prison walls. Our writing process mirrors the essential conditions of prison, where memory lives in breath and body. Where surveillance prohibits documentation and bureaucracy transforms notebooks into contraband, human consciousness becomes the library. Memory sharpens into a recording device more precise than any digital storage because survival demands it. When a man finishes reading Infinite Jest and sets the book down on his bunk, there exists no social media documentation, no highlighted passage preserved in the cloud. There is only the way his shoulders change, the particular silence that follows David Foster Wallace’s final pages, the look he gives his bunkmate that says, You need to read this. Another prison scholar weeping at the loss of innocence in Paradise Lost, unashamed of tears over Milton’s fragile, fallen human beings. The energetic argument that erupted in the prison classroom over MC Escher’s tessellations, whether mathematics could capture infinity. A man pausing mid-sentence while reading Kafka’s The Trial aloud, the weight of recognition stopping his voice entirely. All these moments live only in our memories until, one day, we try to capture them in writing.

Like the weaver who understands that each thread must be placed with intention, Noe’s and my collaborative writing returns to scholarship’s most ancient and sacred technology: human memory, human voice, and the irreplaceable practice of attention and care. In prison, as in our writing partnership, nothing can be casually preserved. Everything must earn its place in memory through the force of its necessity, its beauty, its capacity to survive the narrow bandwidth of constraint and emerge transformed.

What survives this process is what deserves to survive.

“Tend to your own bobbin winding!” Jonathan’s pointed way of telling me to stop filming and pay attention to my own work. Here I was, trying to capture and document the process instead of being fully present to learning it—exactly the productivity trap I’d been trying to escape.