I am five weeks into a semester in London. The pavements and Tube transfers are becoming more familiar, the cultural codes and shortcuts clearer, even as I sense I’m still an outsider when my accent marks me the moment I say “thank you” at a café, or when I need to ask someone to repeat a phrase (spoken in my native tongue, still uncanny in its difference). The light falls differently here. But there’s something honest in these distances, in the way it keeps you attentive.

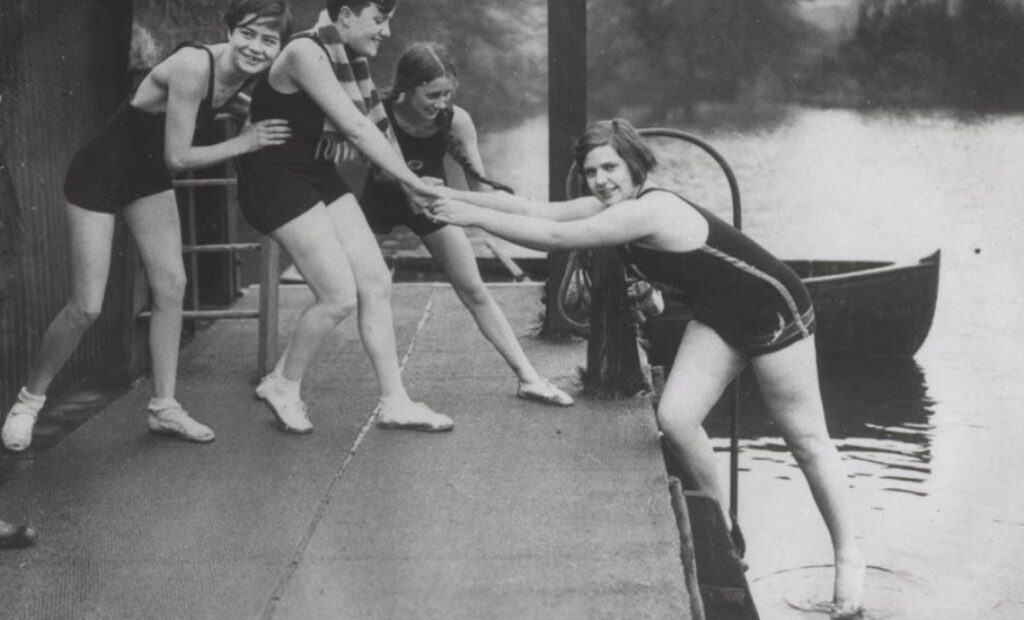

Three mornings a week, I cross Hampstead Heath’s ancient wooded trails to Kenwood Ladies’ Pond for “wild bathing,” where the temperature has dropped to 12°C (frigid compared to the 27°C of an average swimming pool). The British women don’t wince when they enter the water, so I try not to, either. We slip into water fed by the headwaters of the River Fleet, that ancient underground river that once surfaced in the heart of London, and we swim past moorhens and mallards, coots and tufted ducks, even the occasional mandarin duck. One mile through cold water while London wakes up around us.

I’ve also joined the Fleet Singers, a community choir in Hampstead where I’m learning madrigals with neighbors whose lives I’m just beginning to know. It’s strange how this city works—how you can spend your mornings in water fed by a river that’s been underground for half a millennium, your evenings singing Renaissance songs with strangers becoming friends, and your days riding another underground system entirely, the Tube carrying you from neighborhood to classroom and back again.

On Saturday mornings when we aren’t traveling with the students, I walk to the farmer’s markets, fill my backpack with fresh vegetables, then come home to cook for the week. Yesterday, I bought potatoes from a farmer who raises 26 different varieties—I caught about a third of what he said, even though he was speaking English, but his potatoes made delicious soup.

This inaugural year of Oxford College’s London Launch has meant teaching at Gray’s Inn in Central London as guests of IES Abroad, in a Georgian building within one of the ancient Inns of Court where barristers have trained for centuries. Our forty-three students are discovering Shakespeare and metaphor, food history and music, architecture, human rights, British culture, and psychology while learning to navigate a city that is itself a palimpsest—layers of history visible everywhere you look.

Along with the students and my colleague Pablo Palomino, we have traveled to Stratford-upon-Avon where we saw James Ijames’s Fat Ham at the Royal Shakespeare Company, the students discovering how adaptation can honor and transform simultaneously. We’ve been to the West End for Evita, all of us in theater seats watching a different kind of revolution unfold. We’ve travelled by train to Edinburgh and into the Scottish Highlands, where we stayed in a hostel, and I watched students navigate new landscapes with increasing confidence. We traveled to Oxford University, saw Trinity College, and punted on the river.

We’ve learned the practical magic of this city, too: how to grocery shop for only what you can carry home without a car, how the labyrinth of the Underground eventually makes sense (kind of), how walking becomes your primary way of knowing a place.

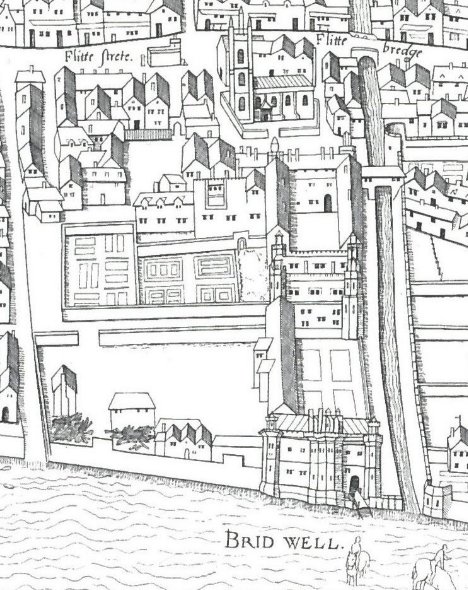

So I’m learning a new kind of familiarity with London, one that comes from living inside it rather than studying it from a distance. But even as I embed myself in the city’s present (the pond, the choir, the Saturday markets, traveling with Pablo and students) I am also researching its past for two different projects. I’m writing about sixteenth-century Bridewell Prison and its system of discretionary sentencing, how social connections, neighborhood vouching, and collective sureties determined outcomes more than the nature of offenses. The prison privileged those with social capital, revealing how even mercy can entrench hierarchy. I’m also tracing the medieval and Renaissance custom of “wearing papers,” the public shame practice for those who violated moral codes, the community enforcing its boundaries through humiliation.

What strikes me is how both then and now, questions of justice come down to questions of community: who belongs, who decides, whose context matters. Walking from the pond to Gray’s Inn to my flat in Hampstead, I’m tracing not just geography but systems of inclusion and exclusion that have shaped this city for centuries. The research isn’t separate from the living. It’s another way of reading the same text.

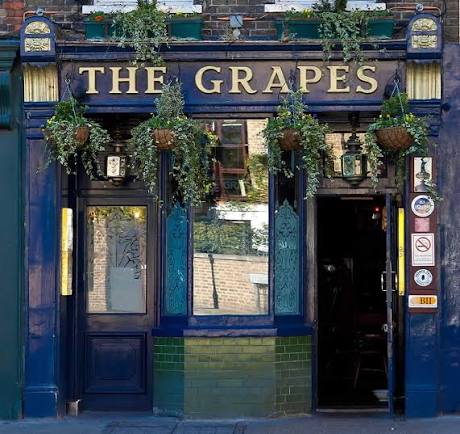

Teaching and traveling alongside Pablo Palomino has been a complete gift. There’s a grace to how Pablo moves through the world, a zen quality that pairs scholarly rigor with genuine enjoyment of life. Whether we’re eating glass noodles at Kiln, haggis in Edinburgh, mussels at the Grapes (Ian McKellen’s pub, five centuries old), or drinking coffee in Stratford-upon-Avon—often with our students and Natalie—Pablo brings the same presence: curious, generous, perceptive, kind. We support each other in ways that make this experiment feel less like work and more like discovering what’s possible when colleagues become friends. Watching him bring his deep knowledge of music and food history to our students, seeing how he creates space for discovery in every market we visit, every walk we take—it’s been a highlight of this inaugural year.

My colleagues Daphne Orr and Natalie Raymond have also brought their extensive preparation, hearts, and minds to this experiment. Together, we’re learning what it means to build community in a new city while shepherding students through their own transformations.

And I love working alongside our British colleagues, whether strategizing travel plans or Pablo and I spending hours on a Friday afternoon with British history professor (and now friend) Ian Stone, discussing the history of London, archives, music, and teaching.

Friends and colleagues have found their way to us: Eva Rothenberg, one of my first students when I began teaching at Oxford and now alumna and friend, came from Cambridge to teach in my metaphor class, bringing her gifts to our students. John Lysaker, fellow prison professor and Director of Emory’s Center for Ethics, visited one evening, and we talked about the work that connects us across institutions and distances. Sheila Cavanagh and I went to a speakeasy then to the brilliant Born with Teeth in the West End.

Five weeks in, I’m watching Oxford students discover what it means to be wholly present in a place, to read a city as text, to find themselves reflected and refracted in unfamiliar streets, to build friendships with peers and professors that will anchor them through their Emory years. They’re thriving in ways that make this experiment feel less like a program and more like proof of what happens when you trust undergraduates to rise to challenges they didn’t know they were ready for.

And I’m learning, too: how cold water can sharpen your thinking, how madrigals sound in a choir loft in Hampstead, how teaching abroad with colleagues who’ve become friends changes the very nature of the work. How a city with roots stretching back two millennia can feel, after just five weeks, like it’s making space for you. It’s been both challenging and exhilarating—the kind of exhaustion that comes from living fully, from saying yes to cold water and road trips and long conversations, from being awake to everything a city and its students have to teach you.

The demands here are relentless in the best way, and I’ve found it hard to stretch between two places, to hold both London and home in my hands at once. So my returned texts, calls, and emails have been slow to family, friends, and colleagues at home. But your community supports me even across the distance.