Dear Dad,

As I reflect on your remarkable life, I’m struck by how you are someone who has refused the fiction that people come in single editions. In a world that often insists we must choose between being intellectual or practical, nurturing or competitive, spiritual or scientific, you have simply lived as if those were artificial limitations. You never argued with the boundaries others accepted for themselves; you just quietly demonstrated that a person could inhabit all of these identities fully and authentically.

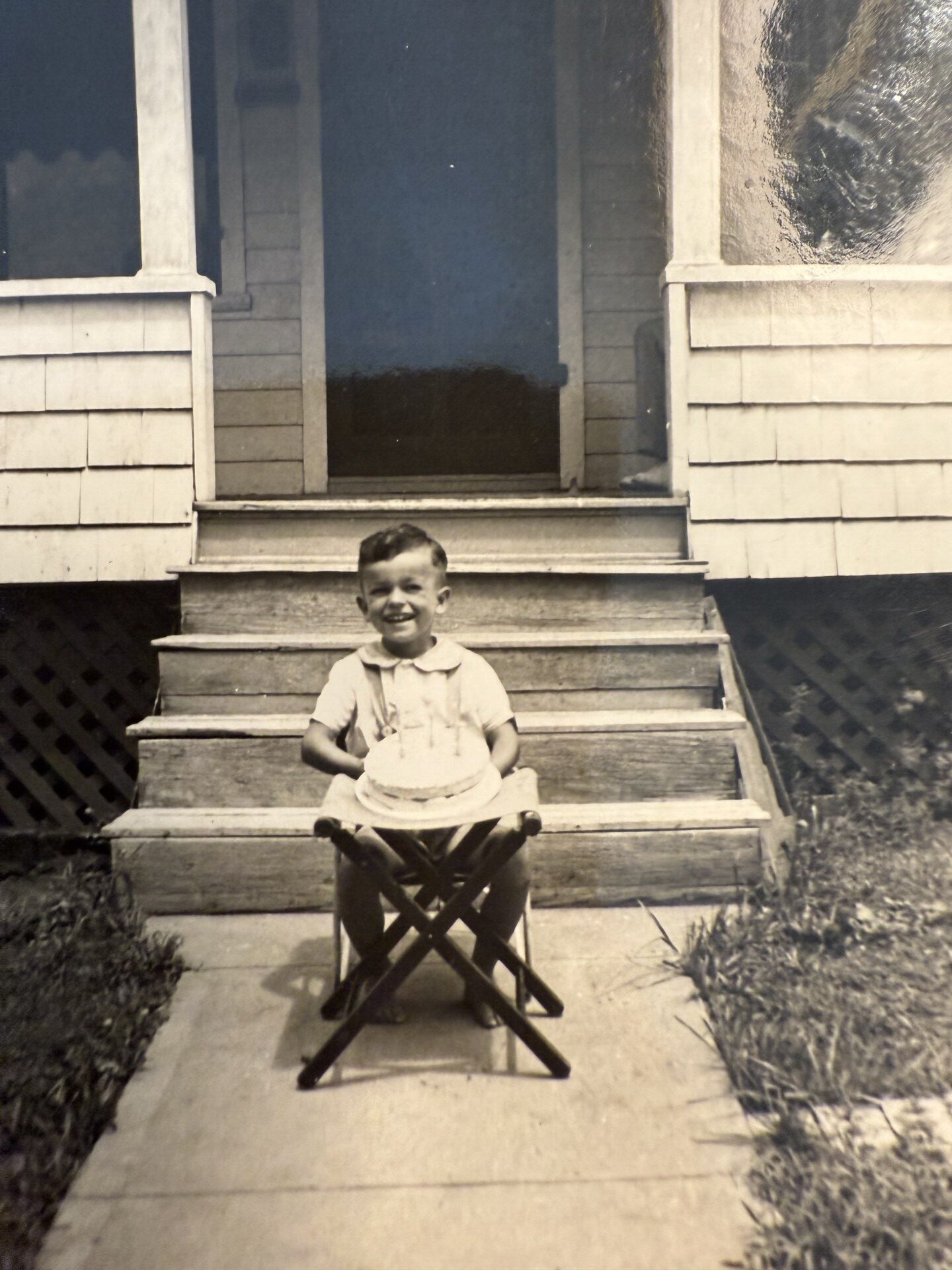

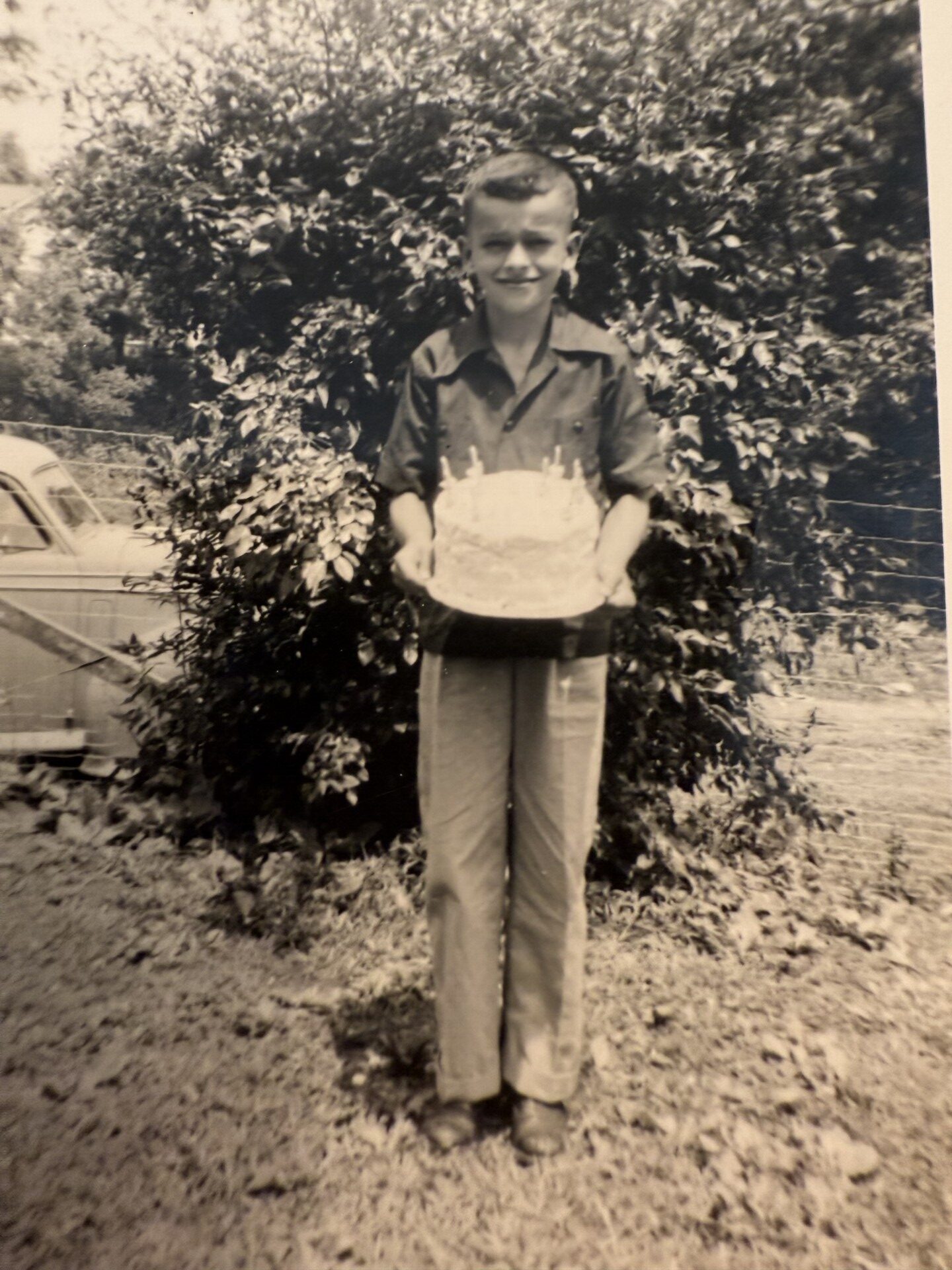

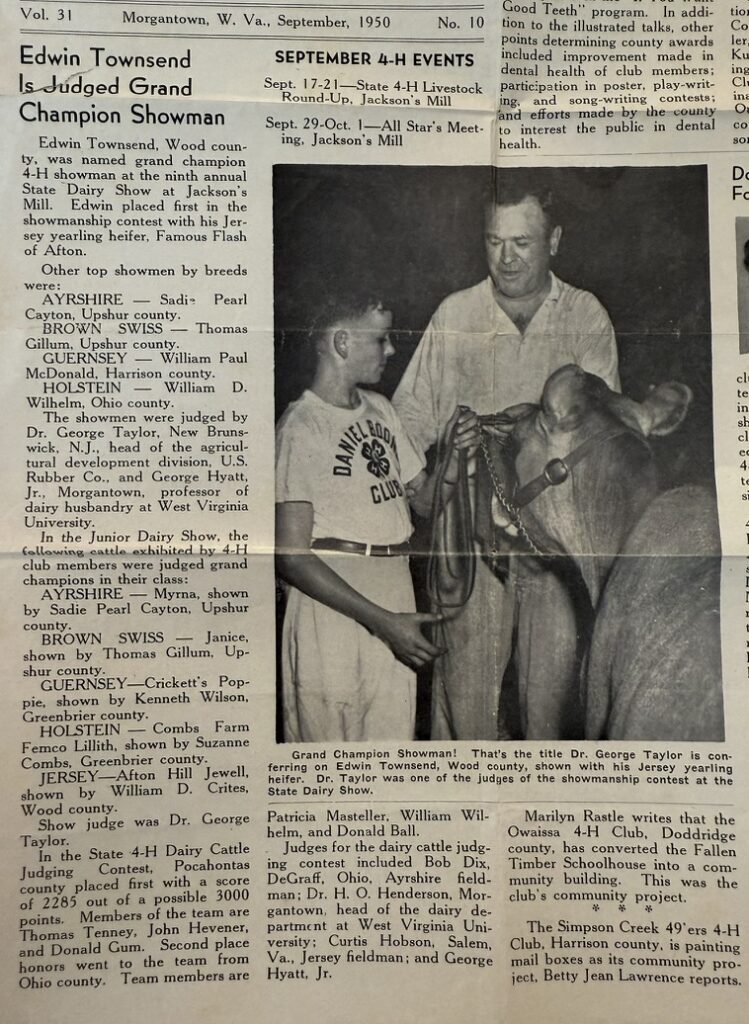

Maybe your early years raising and showing cattle taught you skills that would serve you throughout life: the patience to work with living creatures on their terms, the discipline of daily care regardless of weather or mood, the ability to read subtle cues and respond accordingly. Those 4-H and Future Farmers of America awards represented something deeper than agricultural achievement—they were recognition of someone who understood that excellence came from the integration of mind, heart, and hands.

I picture you at 18, working at the West Virginia University Dairy Farm, sharing quarters with five other guys, earning forty cents an hour with food costs and the cook’s salary deducted from your modest pay. That’s how you put yourself through college. You’d climb into the windowless dairy truck early in the morning after doing chores, riding to freshman classes at WVU—the same institution where you would later return as an Ivy League-educated professor, completing a circle that speaks to your understanding that true education transforms both the learner and eventually, the institution itself.

1957: there you were on the third floor of the WVU administration building, working second shift on an IBM 610 that weighed 800 pounds. (Eight hundred pounds! And now your iPhone weighs 6 ounces.) While the Registrar used the computer during the day for university data, you were there in the quiet hours, processing information for agricultural sciences. You were computing the future: bridging the ancient world of agriculture with the emerging digital age.

Before the 610, you’d mastered the IBM data processing machines, then moved on to the IBM 650 on the main campus. Eventually you would became West Virginia University’s first full-time computer employee. The first. You weren’t just witnessing the computer age; you were helping to build it.

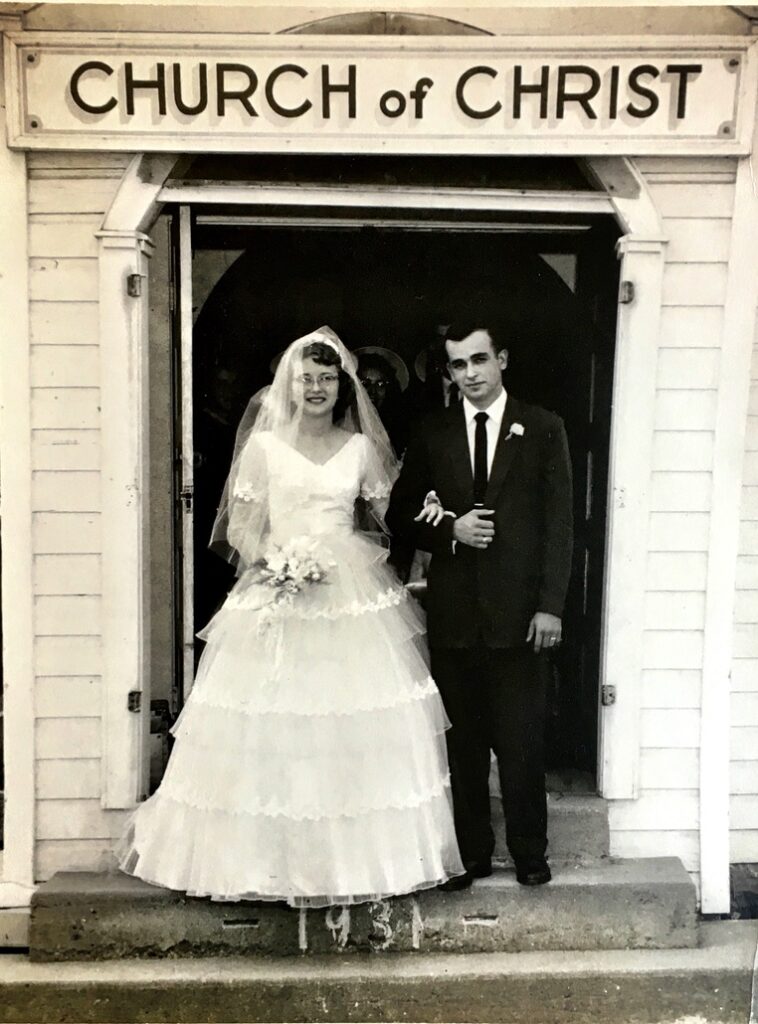

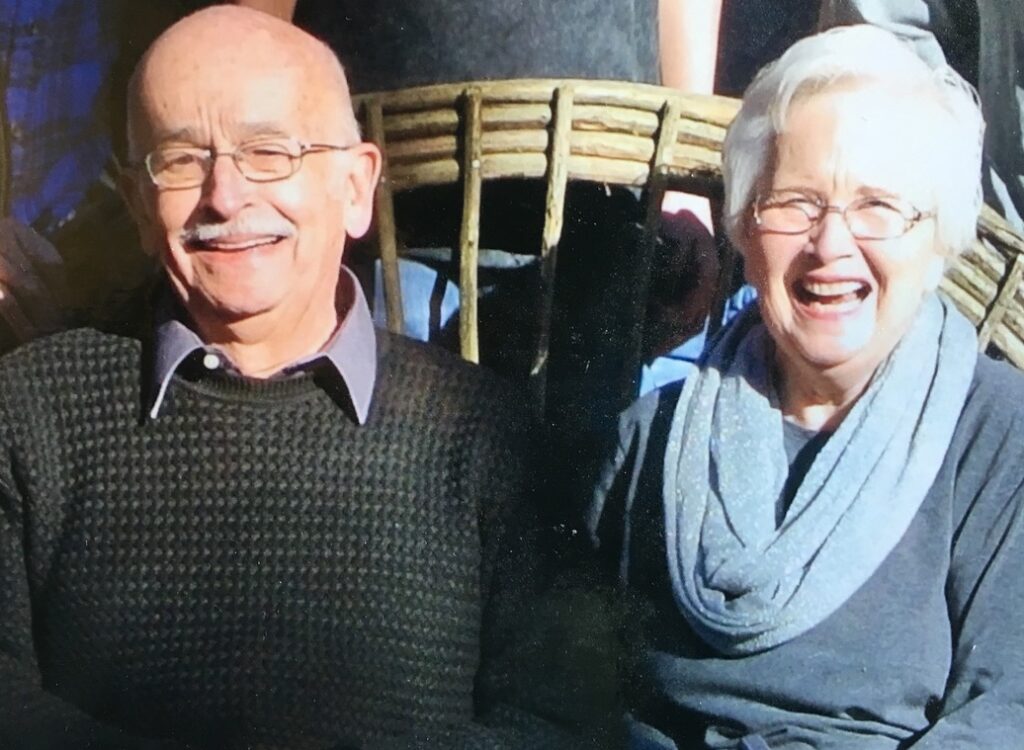

Your marriage to mom—Carol Cochran—became a partnership that would span 64 years and demonstrate your gift for building relationships that last. At Cornell, where you earned your PhD in biostatistics, you and Mom didn’t just pursue degrees and careers; you forged friendships that became our extended family. The Cavenders, the Prices, the Smiths, the Baileys, the Breuers—what laughter and adventures we all had growing up with them and their families. Yearly reunions that created a tapestry of shared memories across decades. All because you and Mom understood that the richest life is one lived in community with others who share your spiritual commitments and who love to have fun.

Mom finished her BA at West Virginia University while you worked, then she taught school while you earned your PhD at Cornell, then you, in turn, supported her while she earned her MA at night—a perfect example of how you approached everything as a team, each person’s growth strengthening the whole.

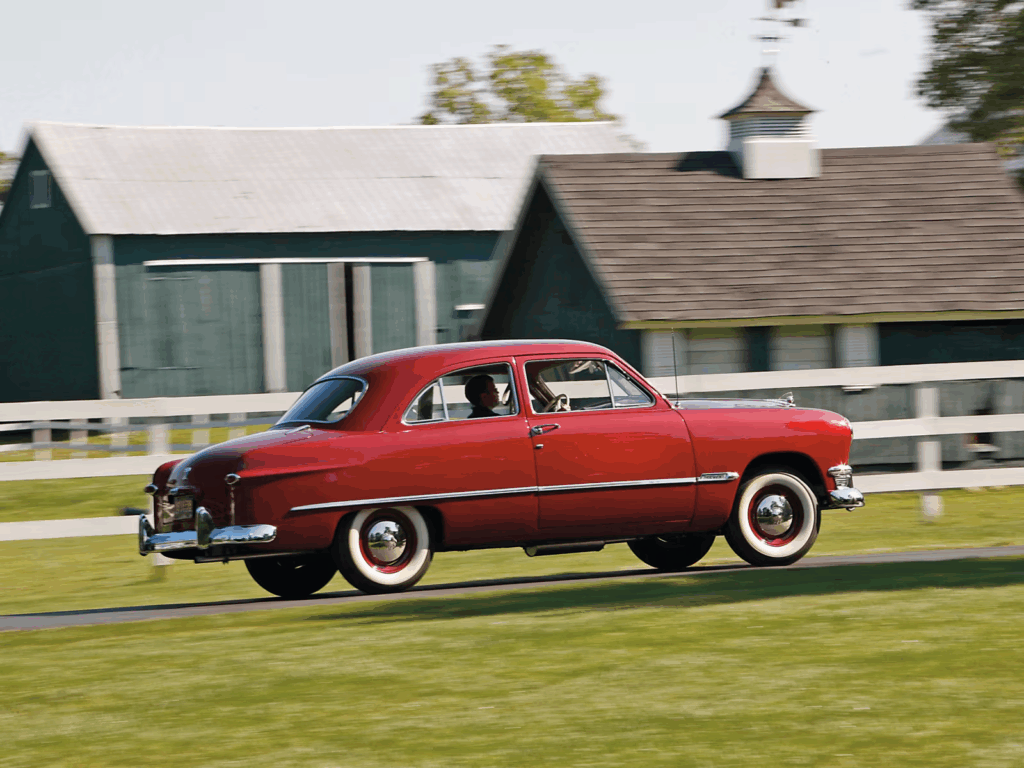

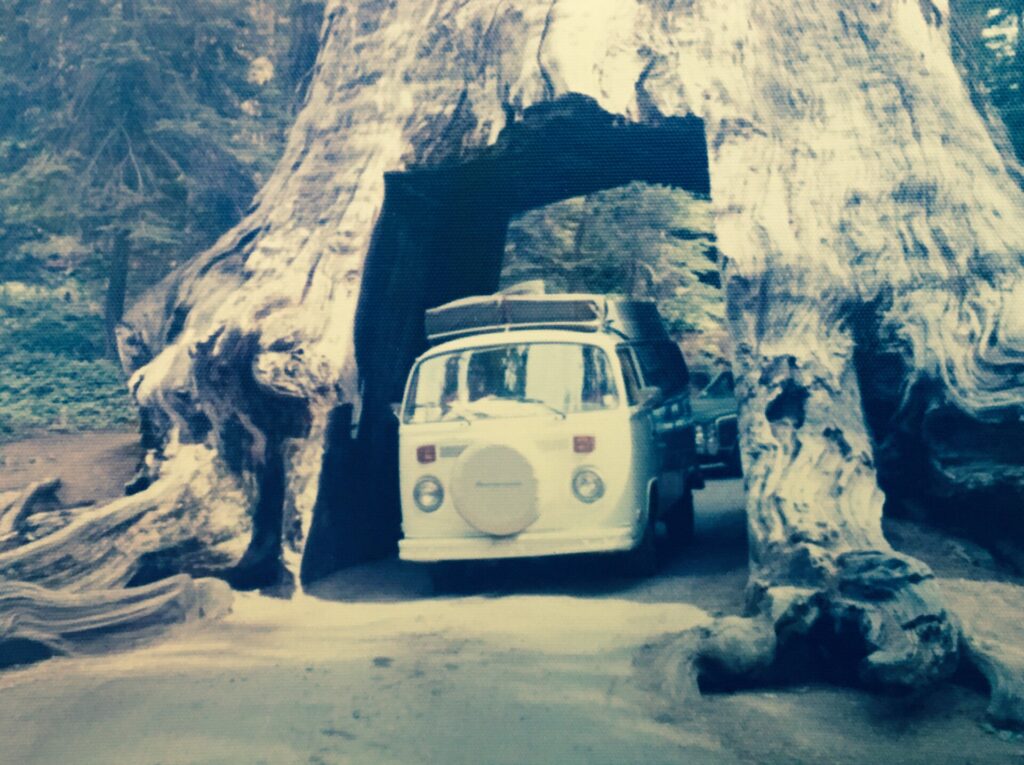

I love envisioning you driving around in that 1949, metallic red Ford Tudor, even with its re-grooved tires painted black. And later, our family’s VW van that would carry us on six-week cross-country camping adventures through the National Parks.

When you loaded us into that VW van and headed for California—with a custom-built box, covered in green shag carpet so one of the kids could sit next to you up front—you weren’t just taking us on vacations. You were modeling that curiosity about the world was as natural as breathing.

When you drove to Florida to ensure we bonded with both sets of grandparents, you demonstrated that relationships require intentional cultivation across generations and geographic distances. When you travelled devotedly to care for your parents after Grandpa had a stroke, you showed us that love manifests in presence, especially during life’s most vulnerable moments. We saw that again when you wouldn’t leave mom’s side throughout three years of cancer treatments.

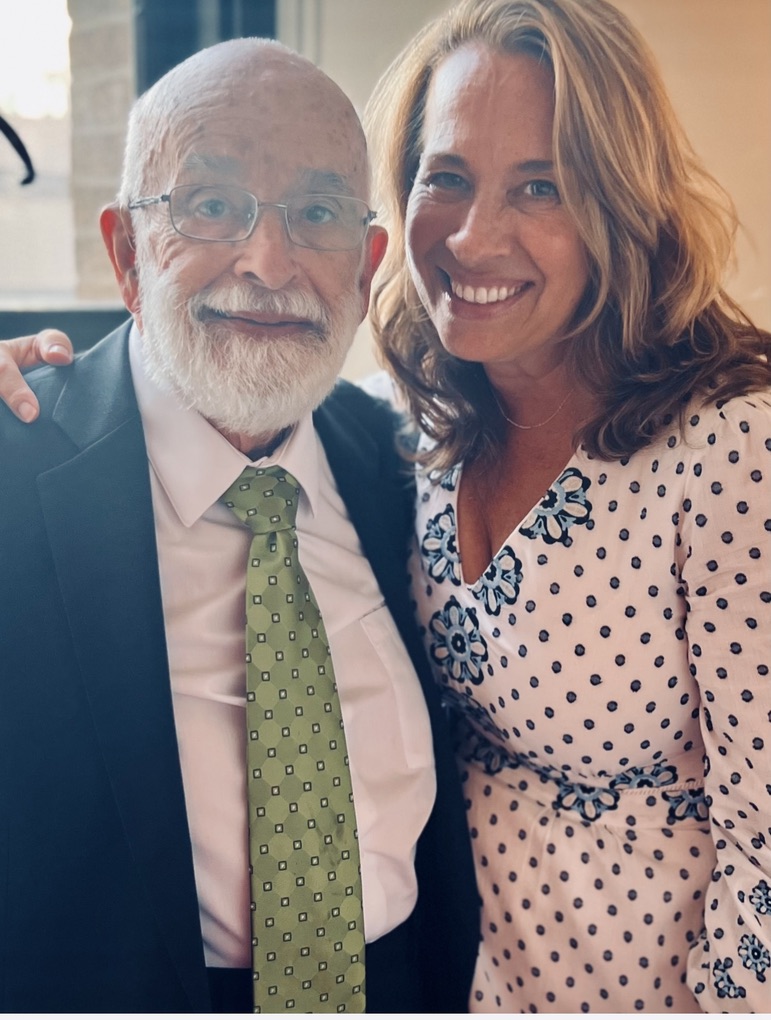

This is why people who “don’t fit in” gravitate toward you, why college students kept coming to those tailgate gatherings you and mom hosted, why grandchildren and great-grandchildren seek your lap for stories. Why our home in Morgantown was filled with friends and family. In your presence, someone could be a serious academic who also loves comics, a competitive athlete who also bakes bread, a spiritual person who also embraces science.

Your children want to please you not because you demand it, but because your genuine interest in whatever captures our attention makes us feel seen and valued. You raised us to be nonjudgmental, generous, and intellectually curious not by giving us lectures, but by living so expansively that we absorbed these qualities like sunlight.

You seem to understand that every moment is a teaching moment—not because you preach, but because you live with such integrated authenticity. When you served as Associate Dean while also helping on the family farm, when you counseled church members with the same care you brought to advising doctoral students’ statistical models, when you listened to your children’s music with genuine interest while also discussing theology—you were teaching us all that a life well-lived refuses to be diminished by artificial boundaries.

Perhaps most profoundly, you taught us that the only time Jesus was angry with people was when they were self-righteous or materialistic—a lesson that shaped our understanding of authentic spirituality as the opposite of moral superiority. To me, this insight is the foundation of your approach to everything: scholarship without arrogance, authority without authoritarianism, faith without judgment.

Your life is a standing invitation to anyone who has ever felt too complex, too varied, or too uncontainable for the roles they are supposed to play. You don’t challenge people’s narrow definitions through criticism or persuasion, but through pure example. Your very existence is a gentle refutation of the idea that you have to pick a lane and stay in it. Because of you, I feel comfortable moving from the prison classroom to my Emory classroom to teaching children at church on Sunday mornings.

From a farm boy working for forty cents an hour to a statistics professor, from that metallic red Ford to the adventure-seeking VW van—Dad, your life spans not just an era of American progress, but an entire philosophy of human possibility. You didn’t just adapt to change; you helped create it while never losing sight of what truly matters: authentic connection, intellectual curiosity, and the radical act of loving people exactly as they are while inspiring them to become everything they might be.

Happy birthday, Dad. Thank you for showing us that the most revolutionary act is simply being completely, authentically yourself.