by Kelly Erby, Assistant Professor of History, Washburn University; PhD, Emory University

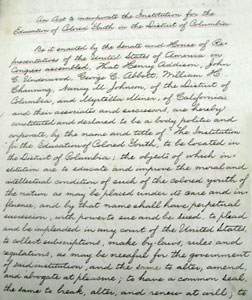

Recently, MARBL acquired the minute book of the Institution for the Education of Colored Youths in the District of Columbia. Located in our African American Miscellany collection, this extraordinary piece of history begins with a hand-written copy of the congressional charter that incorporated the school in 1863 with the purpose “to educate and improve the moral and intellectual condition of such of the colored youths of the nation, as may be placed under its care and influence.” At 197 pages and bound in contemporary marbleboard, this addition to MARBL’s collections promises significance for scholars from a variety of fields, including education and African American and women’s history.

The Institution for the Education of Colored Youths was the legacy of Myrtilla Miner (1815-1864), a New York-born teacher hired in 1846 to teach in Mississippi. Miner was appalled at the condition of the enslaved people she met there and sought to teach slave children. Told in no uncertain terms to go north if that was her goal, she did just that. With the assistance of Harriet Beecher Stowe and others, Miner raised sufficient funds to open the school in Washington, D.C., in 1851 to train free black women to become teachers. In spite of scorn from a significant portion of the D.C. white community (slavery was, after all, widely practiced in the District at mid-century), the school prospered through the 1850s.

In 1861, the school was forced to close temporarily out of concern for the safety of its students. Miner’s health was then in decline and she moved to California in an effort to regain her strength. In her absence, a Republican Congress incorporated the school as the Institution for the Education of Colored Youths, ensuring the school would far outlive Miner, who died in 1864.

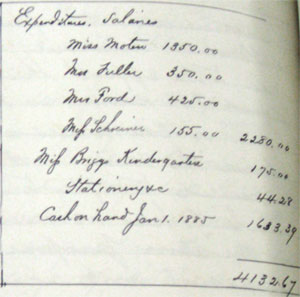

Detail of Expenditures in the Minute Book of

the Institution for the Education of Colored Youths

in the District of Columbia

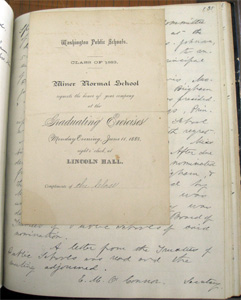

From 1871-1876 the Institute was associated with Howard University. It was then reorganized as the Miner Normal School and became part of the D.C. public school system in 1879. In 1929, it became the Miner Teachers College before merging with Wilson Teachers College in 1955 to form the District of Columbia Teachers College. The school trained African American youth and future teachers for well over a century.

Entries in the minute book faithfully record the minutes of the Institute’s board of trustees meetings during the period from 1863-87. The minutes are written in several different hands, but most of the entries seem to have been penned by Ellen O’Connor, who long served as the board’s secretary (and wrote a memoir of Myrtilla Miner in 1885). During the period covered by the minute book, the board also boasted membership of luminaries both black and white, including Blanche K. Bruce, the Reverend William Channing, and Frederick Douglass.

The book contains reports on the school’s expenses for most years between 1863-87, including teachers’ salaries and building maintenance. In the notations regarding contributions to the school is an intricate web of relationships between the nation’s reform-minded black and white communities throughout the Reconstruction Era. Also, pasted in among the minute entries are various ephemeral items from the school, including newspaper clippings and graduation programs. These programs do not appear to exist elsewhere.

The minute book ends rather abruptly in 1887 with reference to discussion items on the agenda for the next meeting. Nevertheless, the book provides a window into this unique school and the momentous period in which it was undertaken, and is a welcome addition to MARBL.