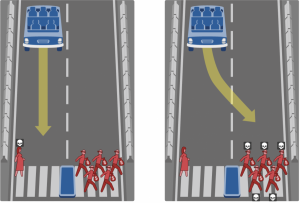

“A double exposure including: a) current day scene From My Lai-Quang Ngai photo by Binh-Dang and b) American ‘Huey’ helicopters during My Lai Massacre on March 16,`968 in My Lai, South Vietnam.”

03/08/2018

For whatever reason reading Jared Afrookteh’s post, “How do we view death in fiction?” reminded me of a class I took a couple years ago called War Crimes and Genocide. I remembered being shocked by all of the atrocious crimes that have occurred throughout history and in the world. I struggled to wrap my head around the events. Massacre in My Lai, genocide in Bosnia, torture in Abu

Ghraib… It is all overwhelming and devastating to learn, as the details behind

each of the aforementioned events, and many more, showcase an unbelievable

amount of abuse and dehumanization that I would have never imagined. And

I also felt a great amount of guilt for having no idea that any of these crimes

had ever been committed.

One of the most appalling war crimes that I learned about was American massacre in My Lai, Vietnam. That may have been the first time I had heard of Americans being the perpetrators committing a crime against humanity. I guess at the time I had always believed that Americans would never commit such atrocious crimes. How could a country representing

peace, freedom, and justice for all completely abandon their moral values and

massacre a community of innocent people? What concerns me the most amidst

growing knowledge of catastrophic death and violence is the fate of the

survivors. How do they reconcile their loss? Often times we see the

establishment of monuments, museums, and other memorabilia to commemorate the event that occurred and the losses people have had so their lives and experiences will never be forgot.

However, does this truly bring closure?

Communities and loved ones may be left without any knowledge of the identity of the offender. Or they may have issues with learning of what happened to the body, as it may be disfigured or missing, which ultimately leaves loved ones without a tangible memory of what they’ve lost. This may also disrupt

traditional burial rituals and require the loved ones of the dead to search for

answers in the hopes of obtaining some form of closure. Or if the perpetrator

is known, it would be ideal to receive a genuine apology or some form of

reparations for their loss, but unfortunately this does not always happen.

For the villagers in My Lai, American Lieutenant William Calley, the man known for leading the massacre in 1968, was convicted for the crime but his sentence was reduced from life in jail to three and a half years, and on top of it all, as

of today, he has failed to make a formal apology or pay reparations to the

survivors. In another case, the Rape of Nanking, government officials of Japan

chose to deny and ignore the fact that their soldiers, killed, raped, and

tortured thousands of Chinese citizens. Even with cries of frustration from

particularly female survivors, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo has been reluctant to

admit any fault and instead focuses on closing the chapter so that it can be

forgotten and future generations of Japan can no longer be connected to that

devastating piece of history.

I think this issue is very interesting but I still have limited knowledge on the specific practices that occur in response to mass death, but I’m looking forward to discussing this in class!

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ghosts-my-lai-180967497/

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/14/shinzo-abe-japan-no-new-apology-second-world-war-anniversary-speech