Linguistic Landscape

Dublin Ireland is comprised of a multitude of cultures and backgrounds which is most inescapable if any time is spent in the city. Various languages are easily observed when walking through the streets, ranging from Portuguese to Romanian. Yet, one thing continuously holds true on the same streets of Dublin; you will always find signs with both the English and the Irish languages posted, everytime.

It becomes interesting that even though we are in Ireland for the summer, there is seemingly little to no purpose of the Irish language being so apparent. Very few Irish citizens admit to being able to understand the language, and even less are actually able to speak it fluently. As mentioned, it’s clear there is a very multicultural and multilingual presence around the city, but I’ve heard no such dialogue being spoken in the Irish language or anything even relatively close to Gaelic, with the exclusion of popular phrases. In truth, only Irish I’ve been able to find actually being useful is the term “Sláinte,” which is equivalent to “Cheers!” in the English language.

The pictures posted are able to highlight the need for cultural presence, if nothing else. Every street sign has its Irish equivalent posted, yet it is obvious that nobody will tell you they live on Faiche Cheapaí.

The Irish language truly only seems to play into the discussed article’s ideas; as it has become a way to more so and evermore commodify both the city and the country. As argued, that despite consumption not being the “totality of social and cultural life” it still plays into the atmosphere of commercialization, and the presence of such a linguistic landscape only furthermore pushes this dialogue along. (Leeman & Modan, pg.2) In such a multicultural city and large tourist destination, it becomes apparent that the Irish language may have once been used indefinitely, but now more so holds the purpose of enlarging this ‘atmosphere of commercialization.’ Dublin has been able to grow, modernize, and therefore commercialize almost everything due to the possibility and reality of such a linguistic landscape and furthermore has been able to influence the public sphere through such means. This idea has been brought to light by the constant, yet mostly unnecessary usage of the Irish language on every street sign, pub, or restaurant. On every corner, one is easily able to spot just another Irish Gift Shop filled with people from all over the world, seeking to include a bit of the Irish culture and language in their everyday lives, if only for the means of falling victim to the commercialized society.

The Leeman and Modan article later makes the point that signs in a specific language can serve a symbolic function that is more so connected to the commodification of ethnically defined places, and only goes to show the “adventurous spirit and openness to other places and cultures as indicative of the current trend in themed environments. (Leeman & Modan, pg.19) In such a themed environment as Ireland, and specifically Dublin, the adventurous spirit mentioned seeks that which is assumed to be Irish culture; anything in green, Gaelic use, Guinness, or whatever aspect of the heritage it may be. And so, again, Dublin, as many cities do, have been able to commodify themselves and their industries to such a degree that the literal use of the Irish language is almost no use, more so a vehicle to push the commercialization of the city, and hold onto whatever piece of history available in the meantime.

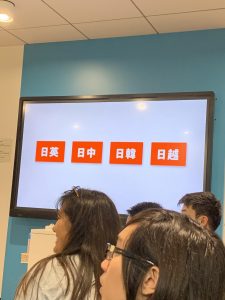

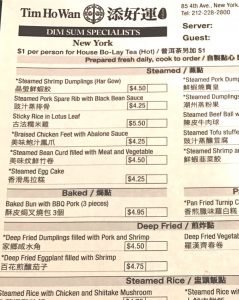

The consumers in these restaurants are unsurprisingly English speakers, so it is very apparent that these restaurants have the same English-speaking customer base. Therefore, the usage of languages other than English is mainly symbolic rather than ideational; these restaurants in essence serve English-speaking consumers.

The consumers in these restaurants are unsurprisingly English speakers, so it is very apparent that these restaurants have the same English-speaking customer base. Therefore, the usage of languages other than English is mainly symbolic rather than ideational; these restaurants in essence serve English-speaking consumers.

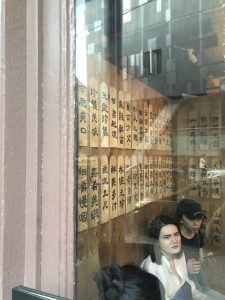

“囍” is pronounced as “Xi”, meaning two good things happening together, often used as an auspicious sign at marriage. In this case, it is very hard to address whether it is ideational or symbolic because none of them makes sense. Ideational? I do not see the connection between marria ge and ramen; symbolic? A red bowl, with a typical Chinese character on it, is too obvious to not to be a Chinese culture representation. I therefore bring my own idea to try to explain this phenomenon in LL. I think as the population from a certain background dominates a small area, anything overall is under the custom from that certain cultural background. Therefore, it can have no meaning but simply a good representation of an extremely strong cultural vitality and presence. Although a bowl quintessentially is different from public sign because it is too trivial to be considered public, it reflects the dominance of a kind of culture. The purveyor of this restaurants can possibly only buy Chinese bowls around this area although he or she did not intend to do so. This area was so small but concentrated that it is an enclave encompassed by financial behemoths, and the very local Chinese presence significantly influenced the local LL.

“囍” is pronounced as “Xi”, meaning two good things happening together, often used as an auspicious sign at marriage. In this case, it is very hard to address whether it is ideational or symbolic because none of them makes sense. Ideational? I do not see the connection between marria ge and ramen; symbolic? A red bowl, with a typical Chinese character on it, is too obvious to not to be a Chinese culture representation. I therefore bring my own idea to try to explain this phenomenon in LL. I think as the population from a certain background dominates a small area, anything overall is under the custom from that certain cultural background. Therefore, it can have no meaning but simply a good representation of an extremely strong cultural vitality and presence. Although a bowl quintessentially is different from public sign because it is too trivial to be considered public, it reflects the dominance of a kind of culture. The purveyor of this restaurants can possibly only buy Chinese bowls around this area although he or she did not intend to do so. This area was so small but concentrated that it is an enclave encompassed by financial behemoths, and the very local Chinese presence significantly influenced the local LL.