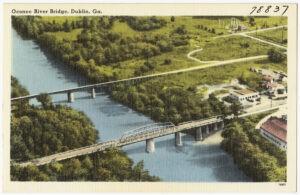

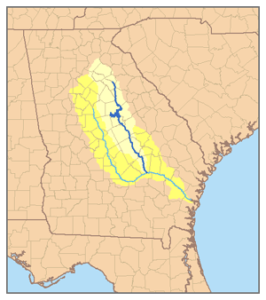

The Oconee river is a 220-mile-long river that originates in Hall County, Georgia, in Oconee National Forest, and ends where it joins the Ocmulgee River to form the Altamaha River. The Oconee flows through two man-made lakes: Lake Oconee and Lake Sinclair. The Oconee river basin drains 5,330 square miles.

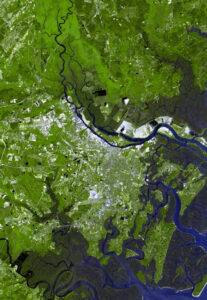

The Oconee river originates in the piedmont region of Georgia, where the rocks are largely metamorphic and resistant to erosion. Here, the Oconee’s channel largely consists of the two man-made lakes. In Milledgeville, Georgia’s former capital, the Oconee crosses the fall line, the boundary between Georgia’s piedmont and coastal plain physiographic regions. The coastal plain consists of younger sedimentary rocks that weather more easily. As a result, when the river enters the coastal plain, it becomes meandering and sinuous. This section of the river features many point bars, cut banks, meander loops, and oxbow lakes. Point bars occur on the inside of bends, where slower moving currents deposit small sediments. On the outside of these bends, faster currents erode the cut bank. As a result, meander loops expand over time until they are cut off, forming oxbow lakes.

Water from the Oconee is used for agricultural purposes and drinking water. The Oconee river basin provides water for more than 250,000 people in Georgia, and irrigates nearly 20,000 acres of farmland. The city of Athens is the largest municipal user of the Oconee’s drinking water. The Oconee is also used for a variety of recreational purposes, like fishing, birdwatching, and paddling. Another example is the Oconee River Greenway in Milledgeville, which includes walking and cycling trails, a dog park, boat ramps, and a farmer’s market.

Post written by Penelope Helm.

Sources/Further Reading:

Georgia River Network. (2018). Oconee River. https://garivers.org/oconee-river/

Oconee River Greenway. Geology of the Greenway and Geomorphic Processes of a Fluvial Environment [Brochure]. http://www.oconeerivergreenway.org/uploads/6/5/3/8/6538602/orgf_brochure.pdf

Oconee River Greenway. Oconee River Greenway. http://www.oconeerivergreenway.org/