Cloudland Canyon Field Guide

Cloudland Canyon State Park, one of the largest and most scenic parks in Georgia, highlights many of the state’s natural vistas. Georgia’s rich geology provides resources such as marble, granite, and kaolin that amount to a large proportion of Georgia’s wealth, and its exterior geologic marvels are a major tourist attraction for thousands each year. The outcroppings along Cloudland Canyon and the surrounding  valley region offers the opportunity to witness the folded and faulted sedimentary layers, and all of the fossilized treasures contained inside them.

valley region offers the opportunity to witness the folded and faulted sedimentary layers, and all of the fossilized treasures contained inside them.

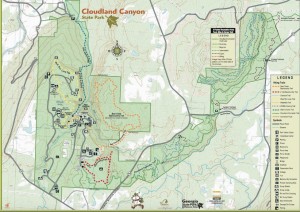

During fieldwork, our team noticed the extensive “passive” recreational development that has interwoven with the natural landscape. Modern developments include natural, cemented, and wooden trails and bridges; acute to severe human impact to the natural landscape due to foot traffic; and the construction of roads, parking lots, and facilities to aid in participation and recreation. Our team drove through the park to the parking lot nearest the main waterfalls. We then explored the trails around the canyon and down to the waterfalls.

It was larger historical context that allows today’s successful park to thrive. The nearby preserved Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site serves as a physical illustration of a chapter within the Georgia Ridge and Valley Region’s cultural geography. An approximate 85.7 miles from the Cloudland Canyon State Park, the Etowah Mounds are emblematic of the kinds of manipulation communities were creating within their landscapes since 1000 AD and possibly prior. The site remained highly trafficked through the Civil War. Later, the park was purchased in stages in 1938 as a component of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression.

Georgia’s rich geology provides resources such as marble, granite, and kaolin that amount to a large proportion of Georgia’s wealth, and its exterior geologic marvels are a major tourist attraction for thousands each year. The state is divided into a patchwork of about four distinct regions: the Piedmont, Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge, Appalachian Plateau, and the Coastal Plain. Since our sites for discussion are located in the Valley and Ridge region, we will focus our geologic discussion on this area.

According to the Georgia Encyclopedia, the upper Piedmont region is separated from the Valley and Ridge because of a great tear in the crust called the Cartersville Fault. The rocks west of the fault line in the Valley and Ridge region are just as old as those in found in the Appalachian Plateau, but due to the nature of the plate collision, they were not subjected to as intense a degree of metamorphism as the Piedmont and therefore contain much of their original sedimentary textures, structures, and fossils. The outcroppings along Cloudland Canyon and the surrounding valley region offers the opportunity to witness the folded and faulted sedimentary layers, and all of the fossilized treasures contained inside them.

This rich geologic history has been altered slightly overtime due to human modifications, leading to current and potential environmental concerns. The park’s 3,488 acres hosts 72 campsites, 10 yurts, 16 cottages, 1 group lodge, 5 picnic shelters, 1 group shelter, 4 pioneer camps, and 13 backcountry campsites. Click here to learn more about the park’s accommodations. The associated anthropogenic traffic into the landscape leads to inevitable wildlife management issues such as barriers to natural animal migration patterns and introduction of non-native species. There is also the potential for crumbling history, as Lookout Mountain’s rich lifeline of animal and human evolution has halted within its current “imaginary” definitions as a park.

Adjacent and preceding development also leads to distinctive impact. Industry causes one of the most identifiable, and long-term, footprints within a landscape, and Cloudland Canyon, Georgia is no exception. Since Dade County’s establishment in the early 1800s, settlers have extracted its resources. According to the Dade County Industrial Development Authority, Dade County’s city of Trenton was first established in a search for coal and iron. Although these resources did not determine Trenton’s wealth, its extraction processes still define the region’s geography. Colloquially, a section of the county on the north end of Sand Mountain is still called Coal City because of the mining that was one done in that area. The area is approximately 11.1 miles from Cloudland Canyon State Park. According to the Industrial Development Authority, Dade County now hosts a population of 16,000. Although mining has ceased, the industry leaves residual impact. Coal and iron ore extraction cause adverse impacts to air quality; it causes an increased risk of solid waste spills; it leads to the increased potential for unknown contaminated soils and sites; and leads to potential water toxicity.

Last but not least, climate change is a present and future concern for all of the country’s state and national parks. The penultimate human modification, climate change can alter fire seasons, plant growth and seasonality, and other long-term landscape shifts. This can also lead to long-term water issues and shortages through the gorge. Planners within the Cloudland Canyon region will need to analyze the region’s source-to-sink patterns, as well as its ecological health, animal migration patterns, and invasive species before approaching any further development. Since the landscape is currently protected as a state park, the region does not need to be concerned with further development beyond passive recreation. However, increased population furthers the potential for adjacent development that can cause just as much damage to wildlife corridors and ecological toxicity as development within the boundaries.

Works Cited

Top Ten Issues Facing the National Parks — National Geographic. (n.d.). Retrieved April 12, 2016, from http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/travel/top-10/national-parks-issues/

“Geologic Regions of Georgia: An Overview.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/science-medicine/geologic-regions-georgia-overview