Dynamited for Gold: The Decline of Northeast Georgia Settlement Patterns and the Demise of the Cherokee Indians

Abstract

Certain towns like Dahlonega in Northeast Georgia boom today due to the successful rebranding of former mining towns as top tourism destinations in the Southeast, while others fade into history. However, the ‘heritage’ boasted by towns such as Dahlonega and Blairsville as mining towns span back only so far to the mid-1800s, and the old German charm of Helen spans back even more recently to the 1970’s. What ties most Northeast Georgian towns together is that they were initially establishments along prominent Cherokee and Creek Indian trails. What were the earliest settlement patterns in Northeast Georgia, and what are the narratives of these often-overlooked communities? How specifically did America’s first major gold rush disrupt the Cherokee and Creek nations and transform future settlement patterns? This paper will seek to give dignity to the heritage of the first Native American settlements in Northeast Georgia, and will analyze how gold, tourism, and other commercial activities have given rise to the Northeast Georgia we know today.

Dynamited for Gold

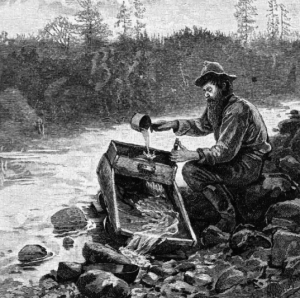

The world may know American gold by conjuring an image of the 49ers, the term used to describe gold miners who rushed to the Sacramento Valley in 1849. However, it is not well known that the first and second major gold rushes occurred in the Southeastern Appalachian Mountains a whole twenty, fifty years prior. The second major gold rush occurred in the Northeast Georgia mountains, and overshadowed the predecessor Carolina Gold Rush in terms of intensity and magnitude of gold seekers. Similarly to the 49ers, the gold prospectors who rushed to Northeast Georgia to take advantage of gold discovery were known as 29ers, as the peak of their rush occurred in 1829.

Miners poured into the Northeast Georgia mountains by the thousands, with estimates ranging from 6,000 miners to 10,000. The 29ers hailed from a hodgepodge of backgrounds, with most coming from out of the state and even from Europe, and a few groups of still-enslaved individuals, freemen, and Native Americans from the surrounding region. Many temporary settlements popped up as a result of mass migration, and these settlements were described as largely unruly and unsanitary, with no formal governance established during such rapid development. Some of these settlements developed into more formalized towns, with varying degrees of success. For instance, the town of Auraria sprung up around a cabin in Lumpkin county and served as the temporary county seat, attracting up to 1,000 settlers in its heyday during the Gold Rush. However, the town only subsisted on gold mine contracts, and once it lost a major lottery for building a major 40-acre mine, it fell into steep decline as its local businesses and offices located to the winning site. The well-known Dahlonega eventually took over the official county seat. Once the gold rush heyday was over and the movement was largely in California, Auraria became a ghost town.

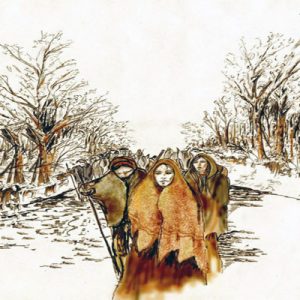

However, before the decline of settlements such as Auraria, there was already a forced decline of Native Americans in the region, pressured by the Georgia Gold Rush. In what became known as the “Great Intrusion”, mining processing facilities popped up on lands that were supposed to be under the control of the Cherokees. Tensions had already existed between Native Americans and white settlers since the Creek Nation had been driven out of the area years prior. Therefore, this existing tension was only further aggravated as mines were spreading like wildfire in most of the Northeast Georgia counties, including even the most northeastern county, Rabun. Just a year after the gold discoveries, then-President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830. In response to this law, the State of Georgia divided up Native American lands and held a lottery to auction the lands off to bidders. Even though the Cherokees objected to this act and took the decision to the courts, the Supreme Court upheld President Jackson’s law and ruled their very existence in the state illegal. Indeed, the Cherokees participated in the tragic 1838 Trail of Tears winter march to designated reservations in Oklahoma.

Soon after the forced relocation of the Cherokees outside of the state, gold reserves started to dry up in 1840, with many sources unable to be mined due to a lack of suitable technology. Furthermore, around the time of the onset of the California Gold Rush in 1949, miners moved en masse out of the state. To further exacerbate the decline of the region, while a federal congressional branch mint that was commissioned to be built in Dahlonega, the mint was plagued by political wrangling and lack of trained personnel to run the mint. Even though hydraulic mining technology was discovered to extract more gold from veins found deep in the hills, the onset of the Civil War disrupted full usage of the technology to bring back a full gold mining industry to the region, and caused the then-Confederate government to close the branch mint in Dahlonega. Indeed, it took extensive revitalization efforts in tourism to revive the area to its reputation today, and even then population growth has only mainly been realized in Dahlonega.

Other Northeast towns and county seats like Blairsville, Tallulah Falls, and Clayton have experienced oscillating population changes and very slight modern-day populations. For instance, despite being the county seat of Towns County, the town of Hiawassee boasts a population of just 916 individuals in 2016, despite having realized consistent population growth since the 80’s. Only time will tell for the fate of these towns as they mainly have no main economy to boast of, and are mainly made up of an aging population. Will they only maintain their existence for the sole purposes of serving as county seats, or if they will adopt similar revitalization efforts and realize the success of Dahlonega? And to what end will efforts to further recognize and reconcile the injustices made against some of the earliest settlers in the region—the Creeks and Cherokees? While the story of the Georgia Gold Rush may bring some excitement and color to one’s imagination of the Northeast Georgia mountains, there exists a dark history of strong prejudice and injustice, and a lingering notion that the settlement patterns created by the gold rush is artificial and unsustainable.

References

“Census of Population and Housing”. Census.gov. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

Chestatee Regional Library System, Digital Library of Georgia, & GALILEO Databases Collection. (2004). “Thar’s Gold in Them Thar Hills” Gold and Gold Mining in Georgia, 1830s-1940s.

Swanson, Drew (2016). “From Georgia to California and Back: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of Southern Gold Mining”. Georgia Historical Quarterly. 100 (2): 160.

Williams, David, 1993, The Georgia Gold Rush: Twenty-Niners, Cherokees, and Gold Fever, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 1570030529