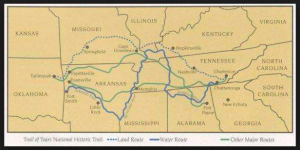

The cultural landscape of Northeast Georgia has a rich history with deep ties to its’ physical environment. Originally inhabited by Native Americans, much of Northeast Georgia was home to the Cherokees before an estimated twelve thousand of them were forcibly removed on May 23, 1838. Forced to relocate by foot to Oklahoma, the journey was long and many casualties ensued. This removal has left a huge scar on our country’s identity that is still visible today. The journey was called “The Trail Where They Cried,” the infamous Trail of Tears (Amerson, 2006). While, this was certainly not the first noteworthy event in Northeast Georgia, it is arguably the most culturally influential and often overlooked.

It is worth noting, positive interactions between Europeans and Natives in this area have also been recorded. However, many of these accounts are anecdotal and reported by Europeans with a clear motive to present things as such. As may be the case for Benjamin Parks, who moved to Hall County (directly below Lumpkin and White Counties) with his family in 1818, on land ceded by the Cherokees. Parks claims that things were friendly and that he even had a romantic liaison with the daughter of a Cherokee Chief. One day in 1828, Parks went deer hunting east of the Chestatee River when he found a bright yellow rock. Suspicious he may have found gold, Parks went to the owner of the property, his local pastor at Yellow Creek Baptist Church, Robert O’Barr. The two men worked out a lease (September 12, 1829) that allowed Parks to mine the land, so long as O’Barr would get one fourth of the gold recovered. When O’Barr realized how much gold there was on his land he wanted more than his agreed upon fourth. Unsuccessful in his attempts to revoke Parks’ lease, O’Barr decided to sell his land to Judge Underwood, who in turn sold it to former U.S. vice president and then Senator of South Carolina, John C. Calhoun in June of 1833.

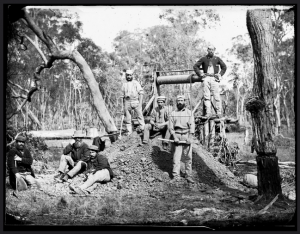

On August 1, 1829 an article appeared in a Milledgeville newspaper about another discovery of gold in Habersham County. This initiated the first american gold rush, and men from all walks of life came to the north Georgia mountains hoping to strike it big. Reportedly, some four thousand miners were mining the sands of the Yahoola Creek by June of 1830. Parks recalls: “all the way from where Dahlonega now stands to Nicholasville, there were men panning out of the branches, and mak ing holes in the hillside” (Amerson, 2006). While early gold mining techniques focused on pan extraction from streams, eventually miners realized that the gold had eroded down the hillsides eventually finding its way into the water. Consequently, tunneling into slopes soon became another common method for miners. And by 1886, electricity was first introduced to mining practices in Lumpkin County. In the same year in Lumpkin, one of the earliest U.S. hydroelectric power plants opened (the first one opened on the Fox River near Appleton, Wisconsin in 1882). By 1906 the gold mining boom was over. From this brief overview of gold mining we gather important insight on how the gold rush affected human cultural attitudes towards natural resources in Northern Georgia.

ing holes in the hillside” (Amerson, 2006). While early gold mining techniques focused on pan extraction from streams, eventually miners realized that the gold had eroded down the hillsides eventually finding its way into the water. Consequently, tunneling into slopes soon became another common method for miners. And by 1886, electricity was first introduced to mining practices in Lumpkin County. In the same year in Lumpkin, one of the earliest U.S. hydroelectric power plants opened (the first one opened on the Fox River near Appleton, Wisconsin in 1882). By 1906 the gold mining boom was over. From this brief overview of gold mining we gather important insight on how the gold rush affected human cultural attitudes towards natural resources in Northern Georgia.

In Dahlonega, on the Public Square, Lumpkin County Courthouse was built in 1836 and is the oldest surviving courthouse in Georgia. Since 1967, when it was converted to the Dahlonega’s Gold Museum, it has been the second most visited historic site in the state. Just northeast of Dahlonega, in White County is Helen, Georgia. Helen is a mountain town known for its vineyards and Bavarian-style village. The once logging town fell into decline around the mid-twentieth century, and the decision was made to transform Helen into a replica of a Bavarian alpine town to draw tourist in. A Bavarian alpine town in the Appalachian mountains that is, instead of the Swiss Alps. The design was mandated through zoning first implemented in 1969. Consequently tourism is the main cultural draw in Helen, serving as a popular weekend destination for the greater metropolitan Atlanta area. Beautiful roads have made Helen a popular draw for Motorcyclists year round. However, the height of cultural activity and tourism in Helen is in late October.

Just northeast of Dahlonega, in White County is Helen, Georgia. Helen is a mountain town known for its vineyards and Bavarian-style village. The once logging town fell into decline around the mid-twentieth century, and the decision was made to transform Helen into a replica of a Bavarian alpine town to draw tourist in. A Bavarian alpine town in the Appalachian mountains that is, instead of the Swiss Alps. The design was mandated through zoning first implemented in 1969. Consequently tourism is the main cultural draw in Helen, serving as a popular weekend destination for the greater metropolitan Atlanta area. Beautiful roads have made Helen a popular draw for Motorcyclists year round. However, the height of cultural activity and tourism in Helen is in late October. Oktoberfest is held annually during the months of September, October, and November. The town is also the host of a stateside Volkswagen and Audi event drawing roughly 20,000 people annually. During the first weekend in June the town hosts the annual hot-air balloon race. Unicoi State Park and Lodge (1,000+ acres) is located northeast of Helen. The park draws environmental tourism to the Chattahoochee National Forest.

Oktoberfest is held annually during the months of September, October, and November. The town is also the host of a stateside Volkswagen and Audi event drawing roughly 20,000 people annually. During the first weekend in June the town hosts the annual hot-air balloon race. Unicoi State Park and Lodge (1,000+ acres) is located northeast of Helen. The park draws environmental tourism to the Chattahoochee National Forest.

Just North from Helen is Brasstown Bald. Located in both Union and Towns Counties, Brasstown Bald is the highest point in the state of Georgia. Cherokee legend tells of a great flood over the lands around the mountain, and a subsequent great spirit who killed all the trees on the top of the mountain so that the natives would have a place to farm. Even farther North of Brasstown, in Towns County is Bell Mountain Park. On a clear day the mountain offers a vista of Hiawassee and Lake Chatuge. In 1963 three men from Murphy, North Carolina attempted to mine the top of the mountain for minerals. This attempt was unsuccessful and resulted in a large opening on the top of the knob. The west bound slope has been the subject of extensive erosion channeling into Lake Chatuge, subsequently affecting water quality. Following the mining disaster the mountain fell into private hands, before it was gifted to Towns County. The county graded out a road and added a viewing platform to make it accessible to the public. As a result, Bell Mountain has become one of the most heavily vandalized places in Georgia. The site is an example of the economic problem, the tragedy of the commons, through the cultural practice of vandalistic (or artistic) graffiti. (Need picture of graffiti in field)

Authored By: Graham Stopa

Works Cited:

Amerson, A. D. (2006). Dahlonega: A brief history. Charleston, SC: History Press.

Harshaw, L. (1976). The gold of Dahlonega: The first major gold rush in North America. Asheville, NC: Hexagon.