by Deborah Dinner

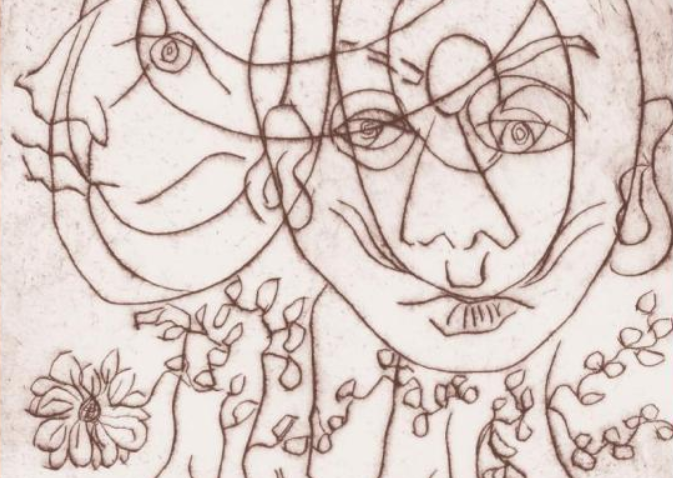

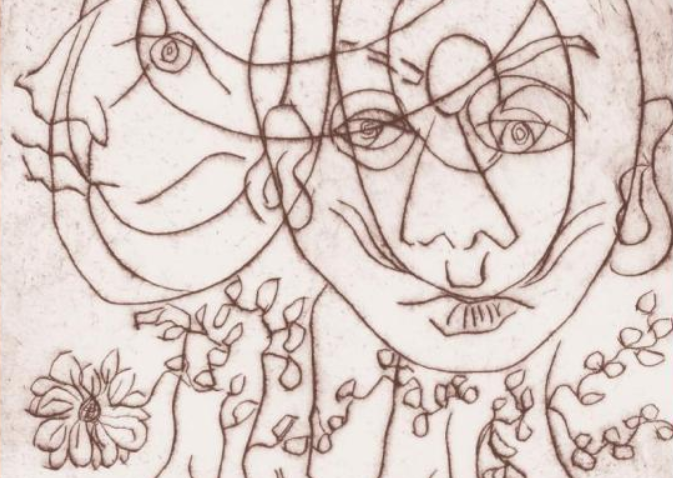

Illustration by Martha A. Fineman

“Take a closer look at a physical copy of Martha Albertson Fineman’s recent book series and you will notice that the cover art is a print of one of Martha’s own etchings. The print shows two faces, one staring intently at the viewer and the other looking to the side. The faces are not isolated; rather, they are connected by intersecting and overlapping spherical lines. Trees and leaves encircle and, perhaps, protect the faces. For me, the emotions evoked by the etchings include curiosity, warmth, forthrightness, creativity, and an awareness of relationship to other people and to the environment. Martha possesses these qualities, as a scholar and colleague. As an artistic medium, furthermore, etchings draw viewers’ attention to negative spaces as well as positive lines. This is the quality of Martha’s scholarship that is, for me, most inspiring and generative. Martha has a knack for rendering visible the negative spaces—the dimensions of law and social life that others are missing.

Over the last decade, Professor Fineman has turned her attention to one such negative space: vulnerability in the human condition. In 2008, she published The Vulnerable Subject: Anchoring Equality in the Human Condition. This essay, since cited by more than 150 law-review articles and countless book chapters, presented Fineman’s critique of the limits of antidiscrimination law and argued that recognition of universal human vulnerability should serve as the ethical foundation for a more responsive state. In the last decade, vulnerability theory has evolved considerably, but I will start my remarks with a brief overview of this landmark essay.

Fineman’s piece starts with a familiar critique: that the formal conception of equality in U.S. antidiscrimination law—same treatment for similarly situated individuals—has proved wholly inadequate either to challenge structures of subordination or to remedy socioeconomic inequality. She draws attention to the way in which the rhetorical prominence of antidiscrimination, as our legal culture’s dominant frame for justice and injustice, reinforces the perceived legitimacy of a restrained state. Putting a twist on our understanding of the public–private divide, she argues that the contemporary state has not withered. Rather, the state refrains from using its formidable coercive authority to guarantee substantive equality.

The essay then proceeds to chart wholly new territory in legal scholarship: universal and constant human vulnerability. Of crucial importance, Fineman departs from the popular conception of vulnerability as signaling the “victimhood, deprivation, dependency, or pathology” of particular groups. Rather, the essay advances the radical notion that vulnerability is a universal and constant aspect of the condition. Vulnerability, she explains, “should be understood as arising from our embodiment,” which carries with it the capacity for “harm, injury, and misfortune… whether accidental, intentional, or otherwise.” Vulnerability also stems from individuals’ differential location in social, economic, and political institutions. For this reason, while vulnerability is universal, Fineman reasons, its manifestations in specific individuals’ experiences are particular and varying.

In my own view, Fineman’s thoughts about the simultaneous universality and particularity of vulnerability offer fruitful terrain for further scholarship. Scholars may explore the points of overlap and departure between Fineman’s theory and critical-race and feminist theories. The latter view vulnerability as institutionally produced and, generally, challenge universalist theories as insufficiently attentive to the construction and deployment of power. It seems that these two approaches to vulnerability may be compatible—a view that should not be surprising given the long and profound role Fineman has played in the development of critical theory within the legal academy. Existential vulnerability, if understood as particular in its manifestation, may support theoretical insights into the institutional production of vulnerability. Fineman and critical theorists of vulnerability similarly highlight the ways in which both state and civic society institutions construct privilege and disadvantage. Indeed, Fineman herself argues that it is not identity traits, themselves, that produce inequality. Rather, “systems of power and privilege . . . interact to produce webs of advantages and disadvantages.”

Fineman’s project, however, is ultimately constructive rather than critical. In keeping with her laudable pragmatism, Fineman’s theory calls for a responsive state that promotes both human and institutional resilience. Vulnerability theory argues that the state has a responsibility to promote resilience by facilitating the just distribution of physical assets such as material resources, human assets such as education and health care, and social assets such as strong, functional families and communities. For the purposes of this Essay, however, I will focus on the concept of human vulnerability rather than its cognate—resilience.

Even at this early stage, the reader might wonder: why does the author, whose primary intellectual identity lies within the field of legal history, find this particular piece of legal theory so compelling? Here is the answer: Fineman’s theory is of considerable interest to legal historians because it is fundamentally concerned with how we should re-theorize law given the inevitability of change over time. I take the occasion of this tribute issue honoring Martha Albertson Fineman’s oeuvre to outline some ideas about the significance of vulnerability theory as a category of analysis in legal history. To begin, vulnerability theory makes historical analysis critical to law by placing historicalchange (and not just originalist inquiry) at the core of legal analysis. Vulnerability theory draws our attention to the fact that human beings are constantly susceptible to change, both positive and negative, in our bodily, social, and environmental circumstances. Vulnerability theory, therefore, reconceives the universal political–legal subject as dynamic rather than static, materially fragile, and socially interdependent. Vulnerability theory is thus well-suited to legal history because it foregrounds temporality as a means to understand social experience as well as institutional arrangements under law. The theory demonstrates that any theory of social justice must account for change over time.

Even as it demonstrates the relevance of temporality for legal theory, vulnerability theory demands that historians pay greater attention to the persistence of enduring and constant human needs across time. Over the last three decades, critical-race and feminist theory has informed historical scholarship by showing how ideas about identity and difference have structured social–legal institutions. Vulnerability theory, I would argue, challenges historians to examine how history is shaped, too, by what Fineman terms inevitable, biological dependency across the life course as well as the derivative dependency of caregivers. These existential characteristics have provoked varied and shifting institutional and legal responses over time. The question for legal historians is how and why law has constructed and reconstructed the institutional arrangements of dependency. Accordingly, recognition of vulnerability can offer new ways to organize historical periodization and theories of causation.

This Essay uses an illustrative example from my own scholarship to demonstrate the capacity for vulnerability theory to enrich legal history. It analyzes the legal construction and obfuscation of vulnerability in the U.S. “welfare regime”: the public as well as private arrangements that order social provisioning. As a short Essay meant to provoke rather than to answer questions, the piece is necessarily cursory in its treatment of historical causation, controversies, and patterns. First, I outline the relationship between gender and vulnerability in the liberal welfare regime, premised on concepts of feminine vulnerability and masculine independence. Second, I discuss the ways in which the neoliberal welfare regime assumes invulnerability: it valorizes sex neutrality, while reinforcing private responsibility for dependency. Third, I use vulnerability theory to help illuminate a historical path not taken: the transformation of the welfare regime according to the model of the universal, interdependent caregiver rather than the universal, autonomous breadwinner. Throughout this brief exposition, I endeavor to explain how Fineman’s theoretical insights inform my own methodology and analysis as a legal historian.”

See more here:

Deborah Dinner, Vulnerability as a Category of Historical Analysis: Initial Thoughts in Tribute to Martha Albertson Fineman, 67 Emory L. J. 1149 (2018).

Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol67/iss6/3