by Martha Albertson Fineman

forth young

gender

Registration is live for both our upcoming workshops:

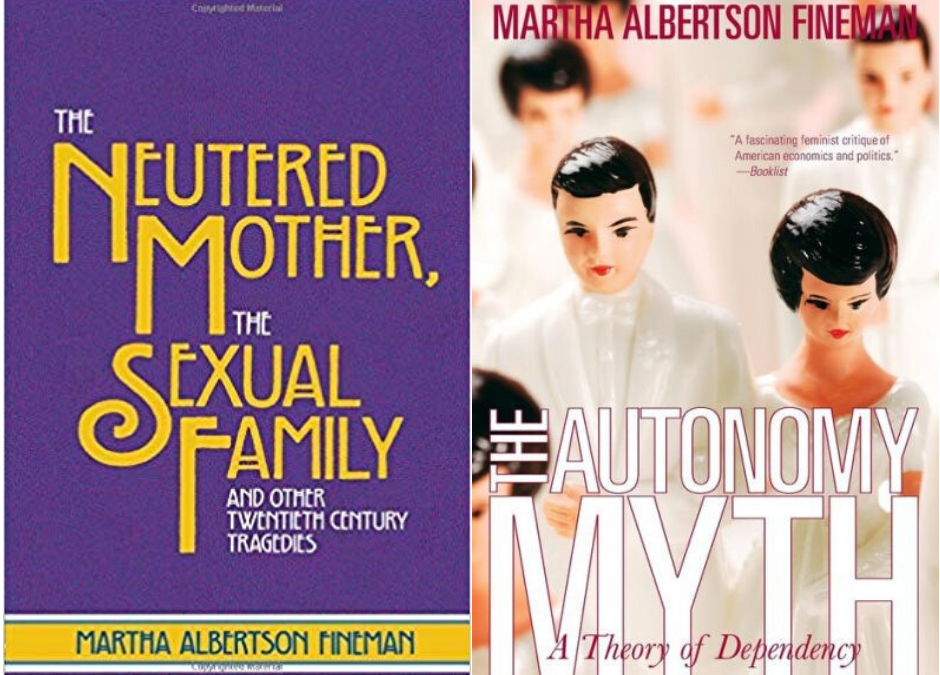

Commemorating Scholarly Milestones: The Neutered Mother at Twenty-Five Years

Vulnerability theory has long been critical of the liberal legal subject and an ideology that privileges consent and contract, manipulating concepts such as choice and autonomy to justify a restrained state. This workshop seeks to explore questions around the legal subject as manifested in its corporate form. The corporation is a legal construct, originally designed to meet social goals. However, throughout the years, and particularly since the rise of neoliberalism in the last decades, it has transformed into an institutional structure that often thwarts human well-being. The recent shift from liberalism to neoliberalism not only re-positioned markets and capital, it also reformulated the idealized legal subject at the center of law and politics. Neoliberal legal subjects—both people and the corporations they form—are reconfigured as “units” of capital that, as such, demand constant investment and management to maximize value. Such units of capital then serve as the mediating institutions through which, according to neoliberalism, social goods are justly allocated and social goals are ideally achieved.

How has this profound shift been accomplished? What role has the perception of the corporation, as a legal construct, played in facilitating such transformation? To what extent have laws and policies been designed to respond to corporate vulnerability or to the need to support corporations by enhancing their resilience? A central tenet of vulnerability theory is that vulnerability is universal – for both natural persons and for legal persons (institutional subjects) created by law and policy. Despite this universality, individual and corporate vulnerability are fundamentally different – individual vulnerability is primary and corporate vulnerability is socially derived. A question can be asked about the ways in which the state chooses to address these universal vulnerabilities – directly, by focusing on individuals’ resilience, or indirectly, but focusing on corporate resilience.

Continue reading A Workshop on Vulnerability and Corporate Subjectivity – Call for Papers

“Introduction

This chapter considers the limited ways in which “injury” or harm is understood in American political and legal culture. In particular, I am concerned with the inability of contemporary constitutional or political theory to interpret the failure of collective or state action as constituting harm worthy of recognition and compelling remedial action. Here, I am not focused on laws redressing harm to private individuals and entities caused by other private individuals and entities. These legal harms are defined in areas of private law, such as tort and contract. Nor am I focused on those legal harms addressed by areas of regulatory law, such as criminal or administrative law. Rather, I am interested in the norms and values that inform the principles governing the exercise of action and restraint on the part of the state when it acts as sovereign and in relationship to individuals as political or legal subjects. As reflected in these foundational documents and constitutional jurisprudence of the United States, these principles express a theory or philosophy of what constitutes legitimate state authority.

The deadline for proposal submissions has been extended to Monday, January 20, 2020.

We are pleased to announce a workshop commemorating the publication of one of Professor Martha Albertson Fineman’s most influential books –The Neutered Mother, the Sexual Family and Other Twentieth Century Tragedies (1995). Twenty-five years after its publication, The Neutered Mother continues to exert a powerful influence on critical and feminist legal studies, as well as the social sciences and humanities at large. We warmly invite a range of scholarly, pedagogical, critical, and creative responses to this important book, as well as reflections upon how it has shaped work on the family, as well as individual autonomy, dependency, vulnerability and the vulnerable subject.

Chapter from Feminist and Queer Legal Theory: Intimate Encounters, Uncomfortable Conversations

“I. STRUCTURING INTIMACY

Core assumptions inherent in our current social and cultural narratives about the family as an institution have tremendous significance in the political and legal definition of the family and, hence, for the fate of mothers. The legal story is that the family has a “natural” form based on the sexual affiliation of a man and woman. The assumption that there is a sexual-natural family is complexly and intricately implicated in discourses other than law, of course. The natural family populates professional and religious texts and defines what is to be considered both ideal and sacred. The pervasiveness of the sexual-family-as-natural imagery qualifies it as a “metanarrative”—a narrative transcending disciplines and crossing social divisions to define and direct discourses. The shared assumption is that the appropriate family is founded on the heterosexual couple—a reproductive, biological pairing that is designated as divinely ordained in religion, crucial in social policy, and a normative imperative in ideology. Continue reading from “The Sexual Family” by Martha Albertson Fineman

“The vulnerability of our embodied beings and the messy dependency that often comes in the wake of physical or psychological needs cannot be ignored throughout any individual life and must be central to theories about what constitutes a just and responsive state. The concept of vulnerability reflects the fact that we all are born, live, and die within a fragile materiality that renders all of us constantly susceptible to destructive external forces and internal disintegration.

Vulnerability should not be equated with harm any more than age inevitably means loss of capacity. Properly understood, vulnerability is generative and presents opportunities for innovation and growth, as well as creativity and fulfillment. Human beings are vulnerable because as embodied and vulnerable beings, we experience feelings such as love, respect, curiosity, amusement, and desire that make us reach out to others, form relationships, and build institutions. Both the negative and the positive possibilities inherent in vulnerability recognize the inescapable interrelationship and interdependence that mark human existence.

The state and the societal institutions vulnerability brings into existence through law collectively play an important role in creating opportunities and options for addressing human vulnerability. Together and independently institutional systems, such as those of education, finance, and health, provide resources or assets that give individuals resilience in the face of our shared vulnerability. A responsive state must ensure that its institutions provide meaningful access and opportunity to accumulate resources across the life-course and be vigilant that some individuals or groups of individuals are not unduly privileged or disadvantaged. Continue reading ‘Elderly’ as Vulnerable: Rethinking the Nature of Individual and Societal Responsibility

“I. INTRODUCTION

Feminist legal theorists can legitimately complain that most mainstream work fails to take into account institutions of intimacy, such as the family. Discussions that focus on the market, for example, typically treat the family as separate, governed by an independent set of expectations and rules. The family may be viewed as a unit of consumption, even as a unit of production, but it is analytically detachable from the essential structure and functioning of the market.

Similarly, when theoretical focus is turned to the nature and actions of the state, the family (if it is considered at all) is cast as a separate autonomous institution. Of course, the state may explicitly address the family as a site of regulation or policy, but in non-family contexts, the extent of societal reliance on the family is un- or undertheorized.

There is little recognition that policy discussions about economic and social issues implicitly incorporate a certain image of the family, assuming its structure and functioning. Continue reading Cracking the Foundational Myths: Independence, Autonomy, and Self-Sufficiency

“I. The Separate Sphere

Society has devised special laws to apply to the family. The unique nature of these rules has been justified by reference to the family’s relational aspects and intimate nature. In fact, “family law” can be thought of as a system of exemptions from the everyday rules that would apply to interactions among people in a non-family context, complemented by the imposition of a set of special family obligations. Family law defines the responsibilities of members toward one another and the claims or rights they have as family members. Family law literature typically focuses on how to use law to redefine, reform, or regulate intra-family dynamics.

But family law does more than confer rights, duties, and obligations

within the family. It also assumes and reflects a certain type of relationship between family and state. During the nineteenth century this relationship was typically cast as one of “separate spheres.”‘ Family (the private sphere) and State (the public sphere) were perceived as largely independent of one another. The metaphor of separation captured an ethic or ideology of family privacy in which state intervention was the exception. Continue reading What Place for Family Privacy?