1. Introduction, Historiography, and Methodology

Is the Manchu language source merely the copy of Chinese source? Does the Manchu language source matter for studying Qing history? The question has been debated for over one century. In this article, I propose to argue that the Manchu language source not only matters but also is at least equally important as Chinese sources.

The oral Manchu language was used by Northeastern China, as known as Manchuria. In 1587, Nurgaci established a regime, and became khan of this area in 1589. In 1616, Nurgaci created a national title, Jin. During this period, because the government requested a more systematic writing so as to enhance the political efficiency, Erdeni and G’agai created the Manchu language based on the Mongolian linguistic system. This Manchu language writing system had limitation to spell non-Manchu language names or places, and, the most importantly, this writing system could not distinguish the sound k, g, and h. Comparing to the later revised Manchu language, this writing system was called the Old Manchu language.

In 1632, Hong Taiji, Nurgaci’s son, asked Dahai to modify the Old Manchu language. The new writing system included ten new words in order to spell names and places, clarified the difference between k, g, and h, and standardized the writing system. Therefore, for about 30 years, the Manchu language was mature enough to become a standard language to use. When the Qing occupied China, the Manchu language became the official language for all regions within the empire, including China, Mongolia, Tibet, and Uyghur until 1911.

In the early 20th century, Japanese scholars had noticed the importance and specialty of the Manchu language. Using the Manchu language sources to study Qing history had become more and more important in Japan. On the contrary, in China, although some scholars understand the Manchu language, using the Manchu language sources to study Qing history did not become a primary research approach at all. There are at least three main reasons.

First, because of Sinization, a lot of scholars did not pay attention on the Manchu language. For these scholars, in the same document, the Manchu language part was just translated from the Chinese part. Second, the amount of Chinese sources is the way more than the amount of the Manchu language sources. As a result, it is not necessary to read the Manchu language. Third, for them, the Manchu language was likely less important after the High Qing, and, meanwhile, ministers’ capacity of using Manchu language had gradually disappeared. As a result, because of these three reasons, the Manchu language sources had not been emphasized for a long time.

In 2004, a new historiographic approach appeared. This historiographic approach is called the New Qing History or the New Qing Imperial History. Over all, the New Qing History proposes to understand Qing history based on three new concepts. First, the New Qing History refuses the Sino-centrism, but, must be clarified, the New Qing History also does not entirely ignore the importance of Sinization. Instead of Sinicization, the New Qing History emphasizes the Manchu elements of the Qing Empire. Second, since the Qing Empire was not a Sinicized empire, the Qing Empire must have its unique. In this context, the New Qing History notices that the Qing Empire was in fact an empire as same as other empires in early modern period, such as the British Empire, Russia Empire, and Ottoman Empire. In other words, the Qing Empire was not a Chinese Empire but a universal empire, and China was just a part of this empire. Third, since the New Qing History emphasizes the importance of the Manchu element, the most direct approach to engage with the Manchus is widely using the Manchu language sources. For the New Qing historians, the Manchu language source is independent instead of a translation copy of Chinese part. Admittedly, the New Qing History generates considerable meaningful results and works, but increasing opponents still judge the three main concepts. One of the most common comments is that the New Qing historians overemphasize the importance of the Manchu language sources in an exaggerative way.

Based on this historiographic debate, this article analyzes a text in Chinese and the Manchu language. The text is Ping Ding Hai Kou Fang Lue (the Book of Strategic Record about Suppressing the Pirate, 平定海寇方略). Fang Lue was a literal form in the Qing period, and this form was only used by the government. When the Qing Empire defeated an enemy, the government edited a book for recording every detail chronologically based on official archives. Because Fang Lue was not only a book recording historical events but also a book proclaiming imperial victory, authority, and prestige, it is reasonable that the book should be edited in to multiple languages. So far, as we known, there were 25 Fang Lue. Among these 25 Fang Lue, Ping Ding Hai Lou Fang Lue was the only one which had not been found the completed version. In the past century, the Chinese version of this Lang Lue was the only version. Noticeably, this Chinese version was just a draft with four volumes. In 2011, I discovered the Manchu language version in the Grand Council Archive. This Manchu language version was also a draft, and it only had the first three volumes. Even though the Manchu volume only included the first three volumes, the Chinese version and the Manchu language version were still comparable because of three reasons. First, they overlapped the first three volumes. Second, they were edited at the same time. Third, they recorded the same event. Therefore, by comparing these two texts, this article seeks the relationship between the Chinese and the Manchu language versions.

As can be seen in Table 1, the Manchu and Chinese texts cover the exactly same period. In other words, these two texts record same events. In fact, this makes sense. Since the main purpose of this book is to record history and proclaim imperial prestige, the two texts should therefore have the same content. However, since the two texts should be in literal the same, it is interesting if there is any tiny difference.

Table 1: The period covered in the first three volumes

| Time | Chinese source | Manchu language source | |

| Volume 1 | Beginning | March 1679 | March 1679 |

| End | December 1679 | December 1679 | |

| Volume 2 | Beginning | March 1680 | March 1680 |

| End | August 1680 | August 1680 | |

| Volume 3 | Beginning | March 1681 | March 1681 |

| End | November 1682 | November 1682 |

This article uses digital analysis to do text mining. The first problem encountered is the difference between two languages in grammar, writing system, and meaning. Because Chinese and the Manchu language are linguistically different, it is difficult, or impossible, to compare words by words. Fortunately, as mentioned above, since the two texts records the same events based on the same sources during the same time, the amount of the proper nouns and the name of places had to be matched. As a result, I propose to compare the amount of the name of places in two texts to see whether the two texts were translated or copied from the other. Then, I seek to individually map the name of places mentioned in two texts, and, by combining the geographic, political, and environmental phenomenon, I try to look for a big picture regarding the difference of the two texts.

2. The Comparison of Two Texts

Table 2 suggests that, besides the term of “Dutch,” the rest name of places appeared more frequent in the Manchu language than in Chinese sources in the volume 1. It is hard to say whether the Manchu language text is more precise than Chinese text. However, this suggests that the Manchu language text and Chinese text are different. Table 3 suggests that the frequency of name of places in the Manchu language text is more than in the Chinese text. Nevertheless, the frequency of Kimmen, Nan’ao, Pinghai, and Tongshan are the same in both language texts. As a result, the two texts are different.

Table 2: The Frequency of the name of places in the Volume 1

| Order | Name of places | Manchu texts | Frequency | Chinese texts | Frequency |

| 1 | Fujian | fugiyan | 38 | 福建 | 20 |

| 2 | Xiamen | hiya men | 14 | 廈門 | 8 |

| 3 | Kimmen | gin men | 11 | 金門 | 7 |

| 4 | Dutch | ho lan | 11 | 荷蘭 | 11 |

| 5 | Tingzhou | ting jeo | 8 | 汀州 | 2 |

| 6 | Taiwan | tai wan | 5 | 臺灣 | 4 |

| 7 | Zhangzhou | jang jeo | 5 | 漳州 | 3 |

| 8 | Youzhou | yo jeo | 5 | 岳州 | 5 |

| 9 | Chaozhou | coo jeo | 5 | 潮州 | 4 |

| 10 | Quanzhou | ciowan jeo | 4 | 泉州 | 2 |

Table 3: The Frequency of the name of places in the Volume 2

| Order | Name of places | Manchu texts | Frequency | Chinese texts | Frequency |

| 1 | Haitan | hai tan | 15 | 海壇 | 12 |

| 4 | Xiamen | hiya men | 10 | 廈門 | 11 |

| 5 | Taiwan | tai wan | 9 | 臺灣 | 8 |

| 9 | Fujian | fugiyan | 8 | 福建 | 4 |

| 3 | Kimmen | gin men | 7 | 金門 | 7 |

| 8 | Penghu | peng hū | 6 | 彭湖 | 3 |

| 2 | Haicheng | hai ceng | 4 | 海澄 | 4 |

| 6 | Nan’ao | nan oo | 3 | 南澳 | 3 |

| 7 | Pinghai | ping hai | 3 | 平海 | 3 |

| 10 | Tongshan | tung šan | 3 | 銅山 | 3 |

Comparing to the previous two volumes, Table 4 shows a different result. Besides the Taiwan, Fujian, and Penghu, the rest of frequency is the same. However, it is apparent that frequencies of Taiwan and Fujian in the Manchu language text are more than in Chinese. Although the texts in the Manchu language and Chinese are slightly different, in terms of name of places, most of them are the same in the volume 3.

Table 4: The Frequency of the name of places in the Volume 3

| Order | Name of places | Manchu texts | Frequency | Chinese texts | Frequency |

| 1 | Taiwan | tai wan | 19 | 臺灣 | 11 |

| 3 | Fujian | fugiyan | 16 | 福建 | 12 |

| 2 | Penghu | peng hū | 8 | 彭湖 | 7 |

| 4 | Kimmen | gin men | 3 | 金門 | 3 |

| 5 | Xiamen | hiya men | 3 | 廈門 | 3 |

| 7 | Zhejiang | jegiyang | 2 | 浙江 | 2 |

| 8 | Pingyang | ping yang | 2 | 平陽 | 2 |

| 6 | Haicheng | hai ceng | 1 | 海澄 | 1 |

| 9 | Tongshan | tung šan | 1 | 銅山 | 1 |

| 10 | Yungxia | yūn siyoo | 1 | 雲霄 | 1 |

Since I have compared the frequency of name of places in the first three volumes, it is obviously that the two texts are different. Although the difference is slight, they are different. Therefore, the Manchu language text or Chinese text are not the translated or copy version from the other. Using diagram is an appropriate approach to see how different the two texts are.

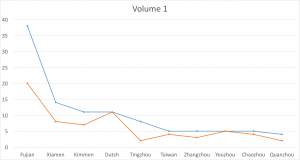

Graph 1: The line-graph of the difference in the Volume 1

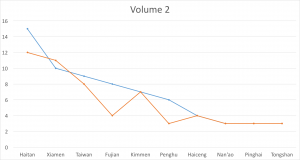

Graph 2: The line-graph of the difference in the Volume 2

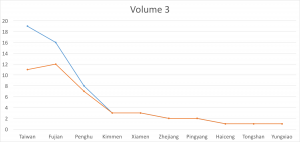

Graph 3: The line-graph of the difference in the Volume 3

As can be seen, Graph 1, Graph 2, and Graph 3 suggest that the two texts are different in the most frequent name of places. In other words, the more frequent places are mentioned in text, the more different they are. When a place where are mentioned only few times in either text, this suggests that this place was only becoming significant at a certain moment or event during this period. For example, in the volume 2, Nan’ao, Pinghai, and Tongshan were mentioned only because a minister listed certain places where should be garrisoned. Besides this suggestion, these places were not important; to be specific, they should not be mentioned because they were not even the territory of the Qing Empire due to the Coastal Exclusion Policy. I will discuss this in the next section. Therefore, once the places were mentioned more frequent in the texts, they were highly different. In other words, I can confidently conclude that the two texts are different in terms of the frequency of name of places, even though they recorded the exactly the same period and event.

3. A big picture of the geographical phenonmenon

In the previous section, I have left a question that the less frequent name of places should not appear due to the Coastal Exclusion Policy, but why were they still mentioned in two texts? This question might be able to answer when I incorporate the text mining with mapping together. According to the texts, the first sentence of the volume three addresses an important event. In the second month of the twentieth year of Kangxi Reign Period, the Qing Empire decided to repeal the Coastal Exclusion Policy. In other words, the lands in coastal area abolished due to the Policy could be used by people and government. However, this policy in fact was not successful because a lot of people still returned to their hometown before the policy repealed. This was widely known in Fujian but not in other regions.

In other words, the records in the volume 1 and 2 were the events when the Coastal Exclusion Policy was processed. However, the volume 3 was the record after the Coastal Exclusion Policy just repealed. Therefore, I propose to combine the result of the volume 1 and 2 as one fact but keep the volume 3 as an individual fact to discuss the difference between two texts under the historical phenomenon.

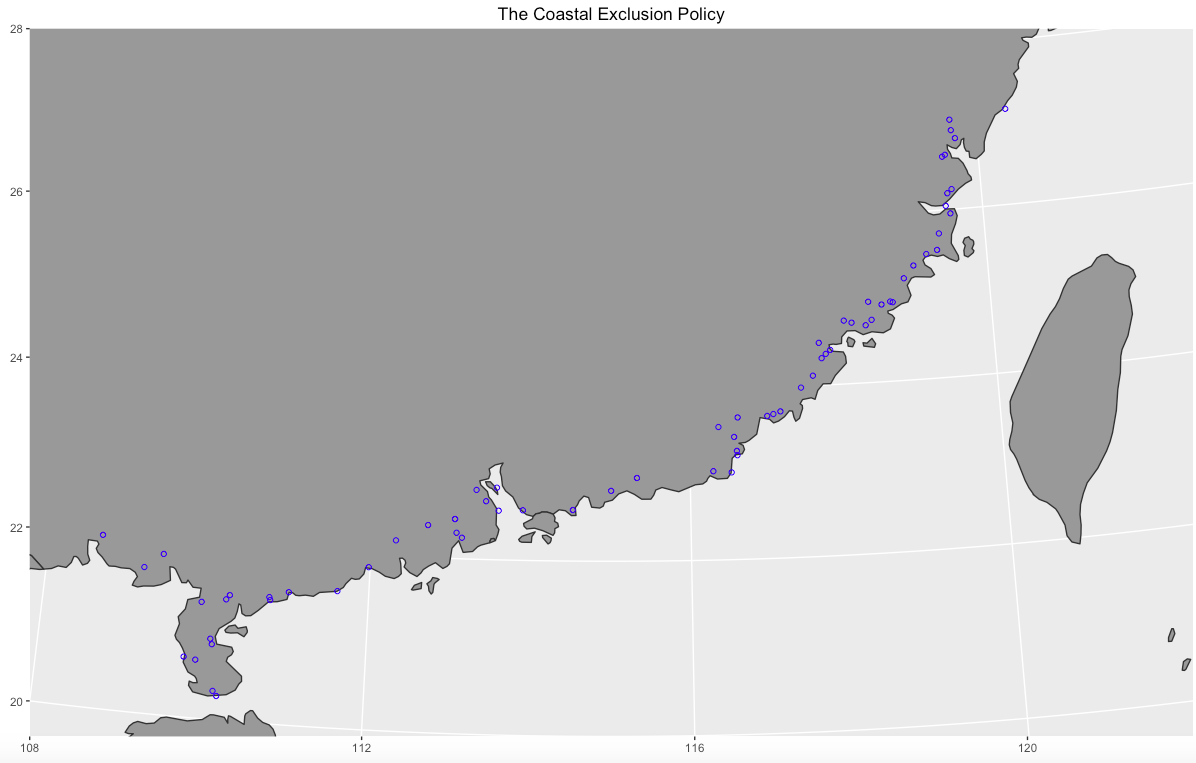

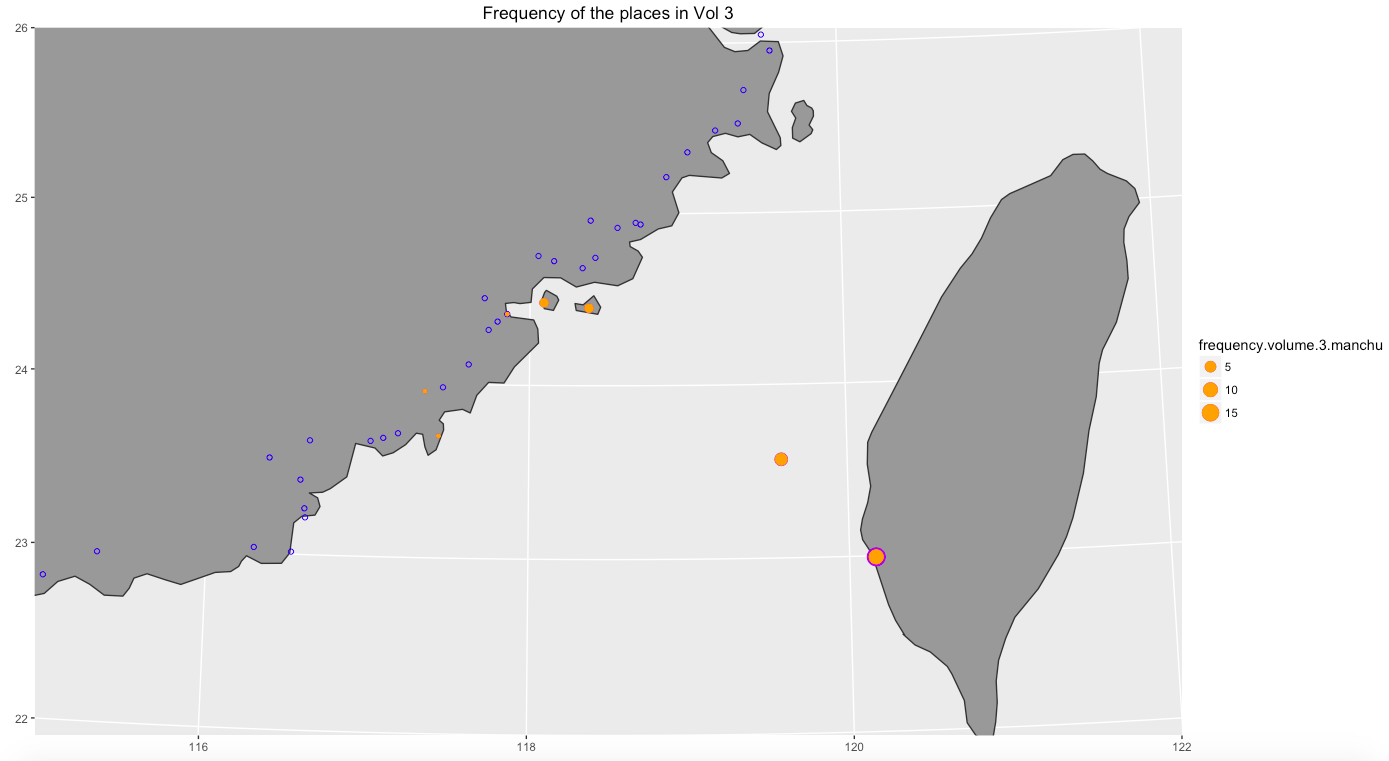

As can be seen in Map 1, between the frontier of blue points and seashore, the coastal area was entirely abandoned by the Qing Empire, so the area was in literal not a part of the empire. Therefore, when I mix the result of text mining and the mapping, this might help to understand history well.

Map 1: The Coastal Exclusion Policy

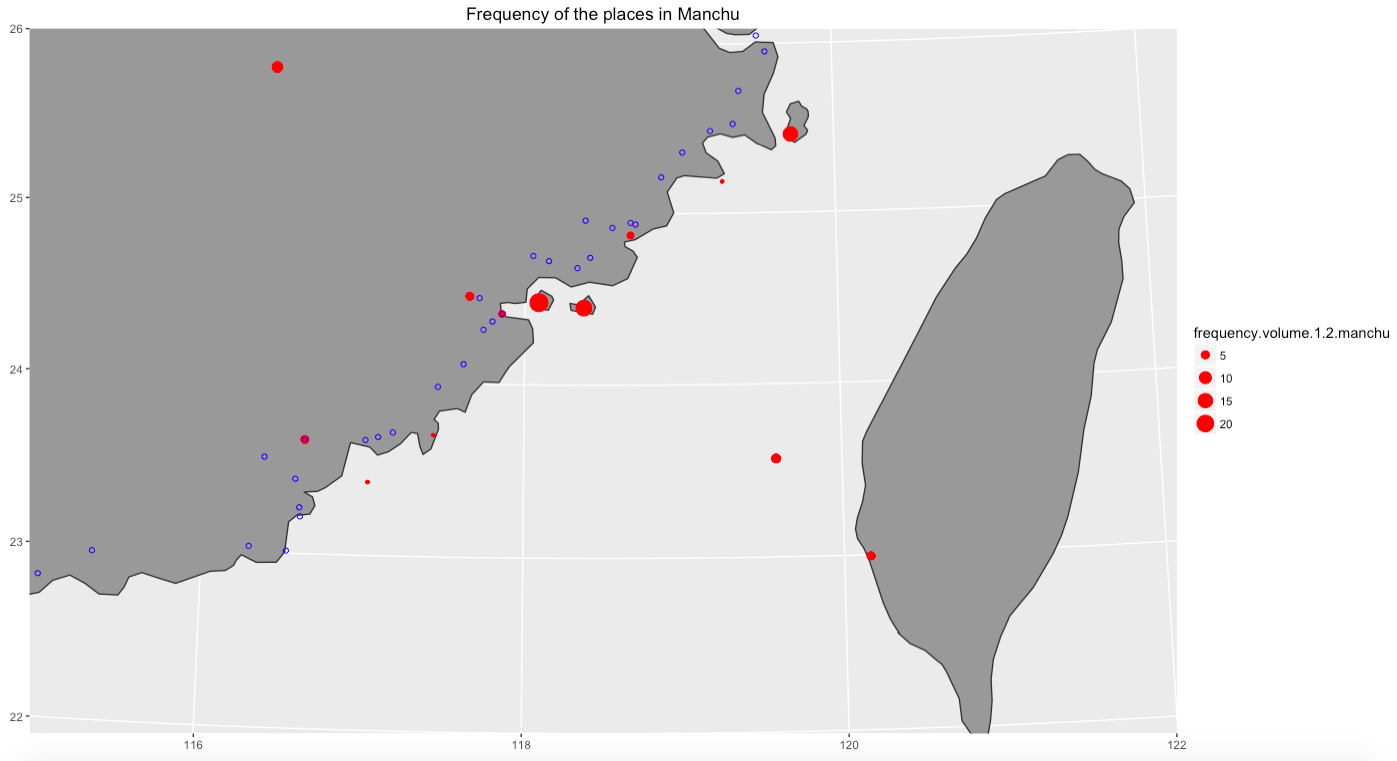

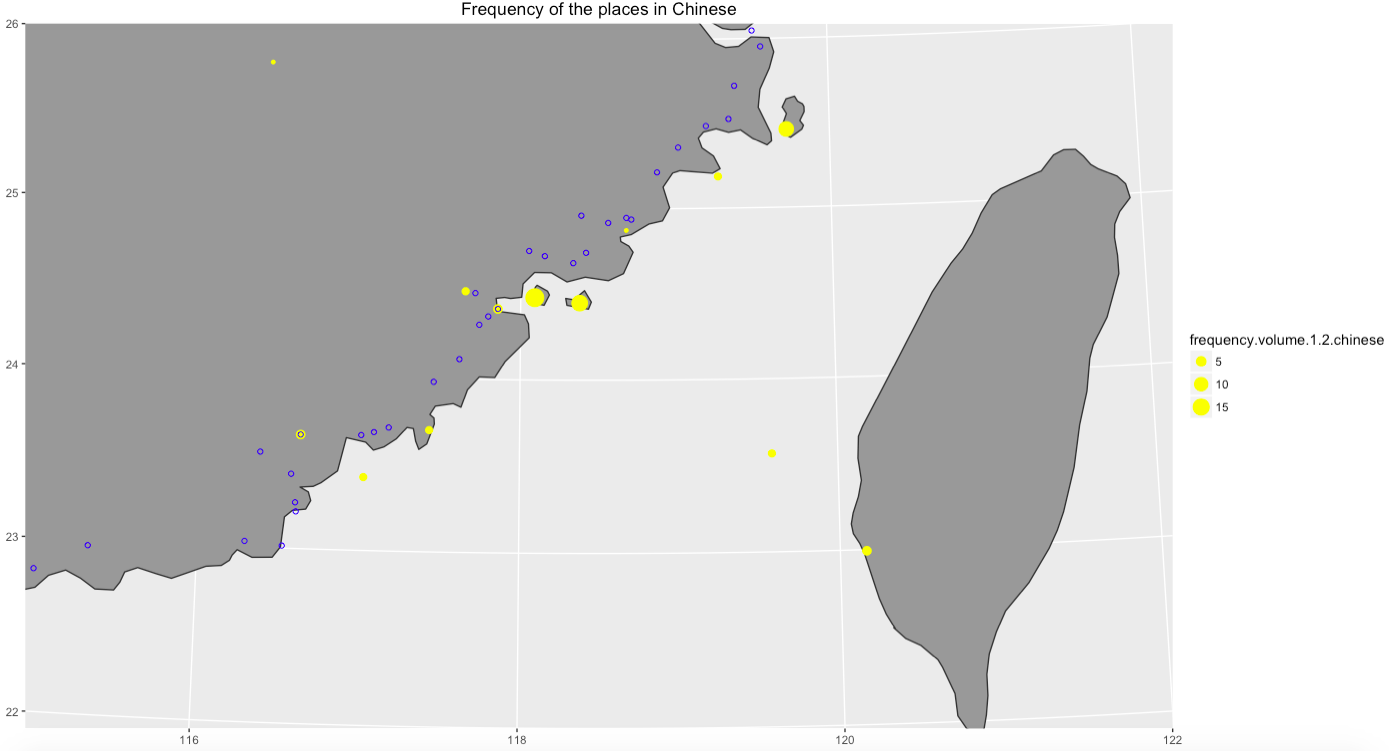

Map 2 is drawn by combining Map 1 and the result of Table 2, but I erase the large unit of place, such Fujian and Dutch, because I could not identify them in the map. As can been seen, the cities mentioned in text were almost beyond the front line, besides one point, which was Youzhou. In other words, from 1679 and 1680, the most frequent discussion about places located on the area where was belonged to neither the Qing nor the Zheng. By using the similar approach, Map 3 shows the result of Table 3 in the map.

Map 2: The frequency of places in the Manchu language in the volume 1 and 2

Map 3: The frequency of places in Chinese in the volume 1 and 2

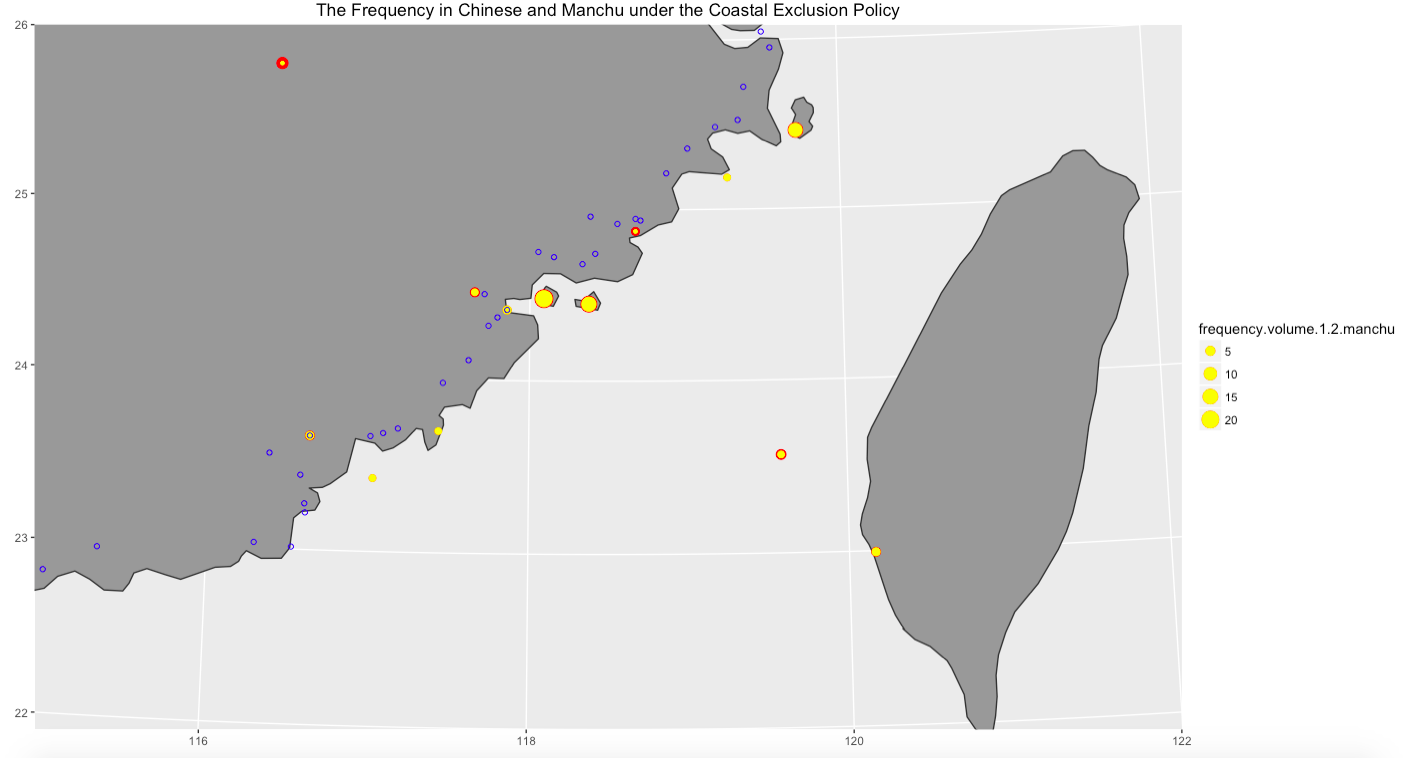

Combining Map 1, Map 2, and Map 3, we could gain Map 4. It is interesting the difference between the Manchu language and Chinese sources in the map. Since the Manchu language mentioned these areas, where were not a part of the Qing, more direct than in Chinese, this is probably meaningful. Considering the feature and audience of the Manchu language, the Qing government probably did not allow Chinese general public, who could easily access to Chinese but the Manchu language, to understand details of the failure of the Coastal Exclusion Policy. In other words, this difference might imply how the empire control people’s mind and recognition of the true history.

Map 4: The frequency of places in the Manchu language and Chinese in the volume 1 and 2 under the map of the Coastal Exclusion Policy

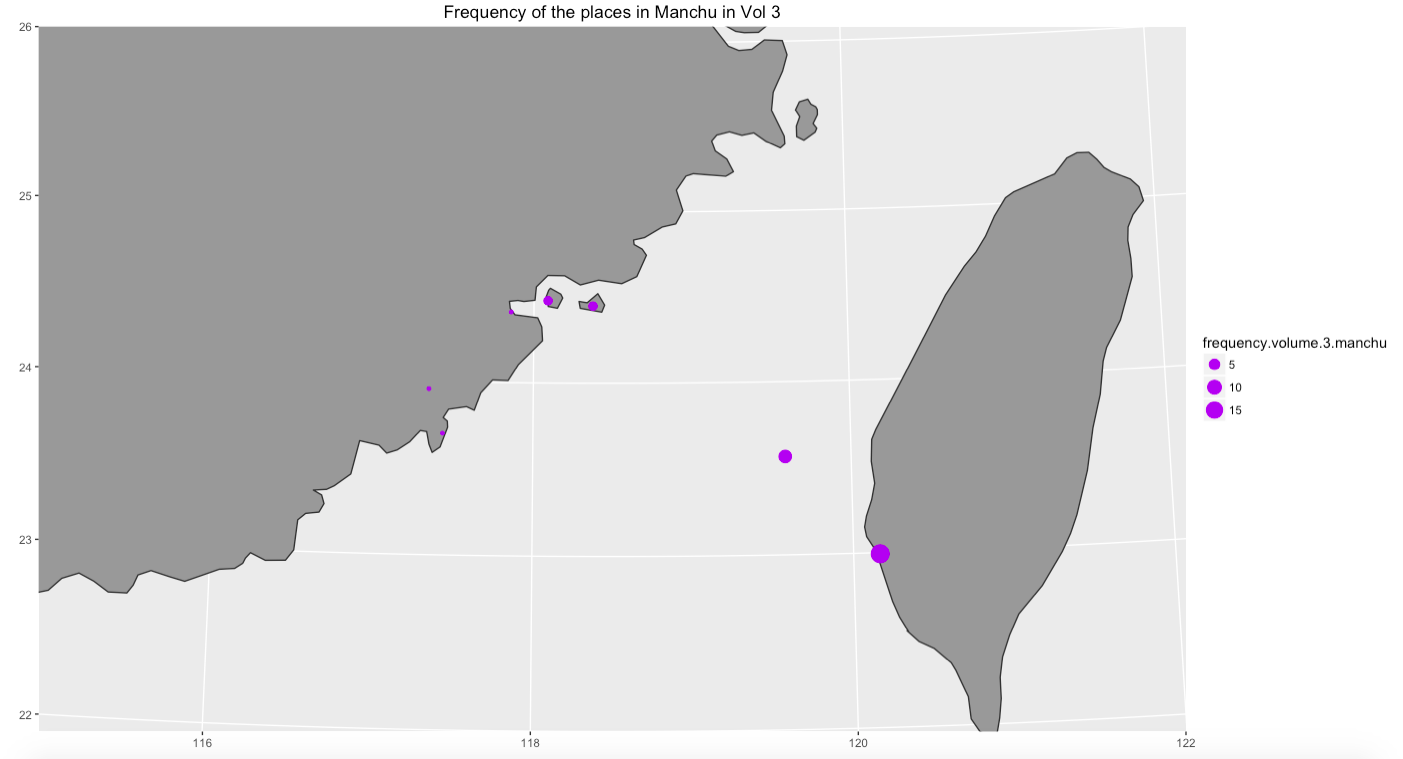

What was happened and changed when the Coastal Exclusion Policy was repealed? In fact, although the government prohibited people to return these abandoned areas, increasing people still returned where they settled before the policy processed. As a result, the policy was in reality useless. When the policy was repealed in 1681, people could return their original hometowns and lands. According to the previous discussion, if it is true that the reason to mention cities in abandoned area in Chinese less frequent and direct than in the Manchu language is because the government attempted to control people’s understanding, Map 5, Map 6, and Map 7 could exactly interpret why the two texts are similar in the volume 3. Because the Coastal Exclusion Policy had been repealed, it was not necessary to hide from anything about the fail of Coastal Exclusion Policy.

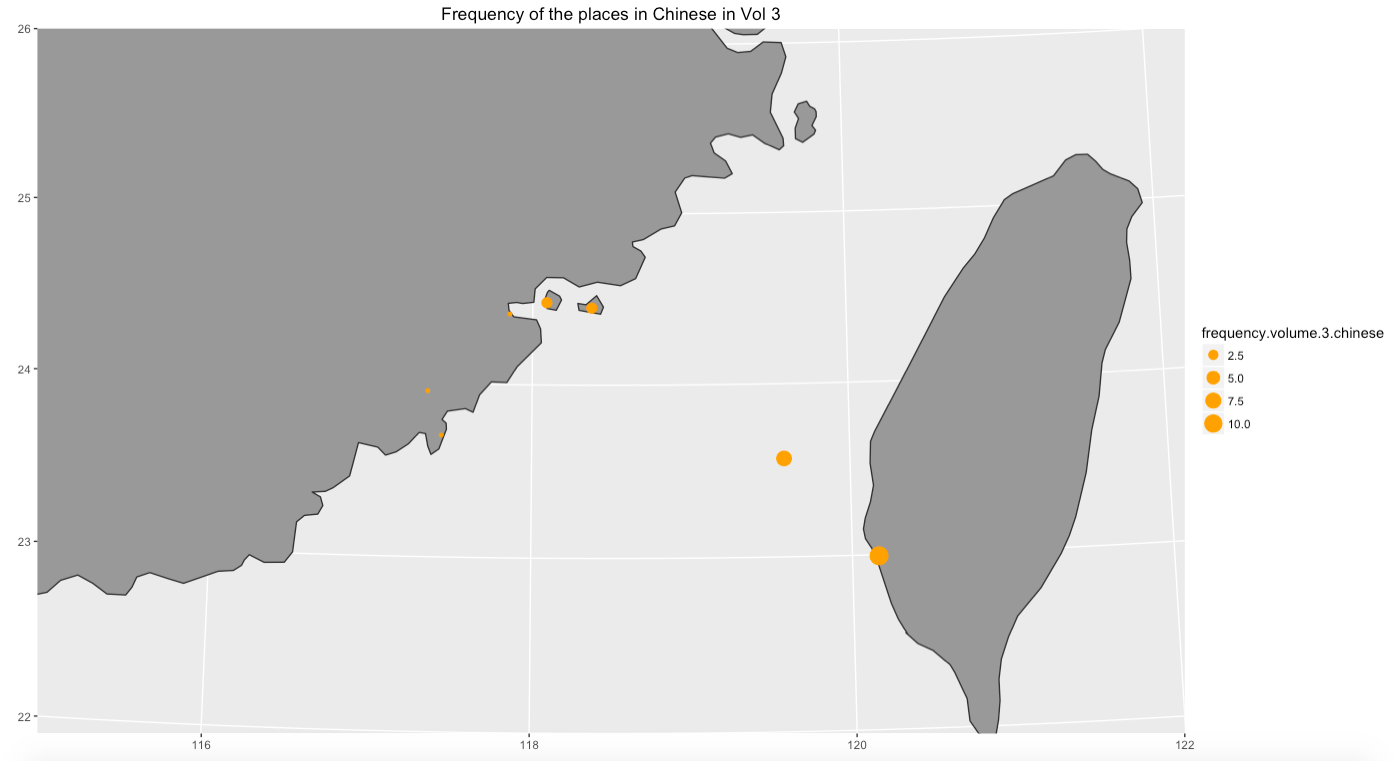

Map 5: The frequency of places in the Manchu language in the volume 3

Map 6: The frequency of places in Chinese in the volume 3

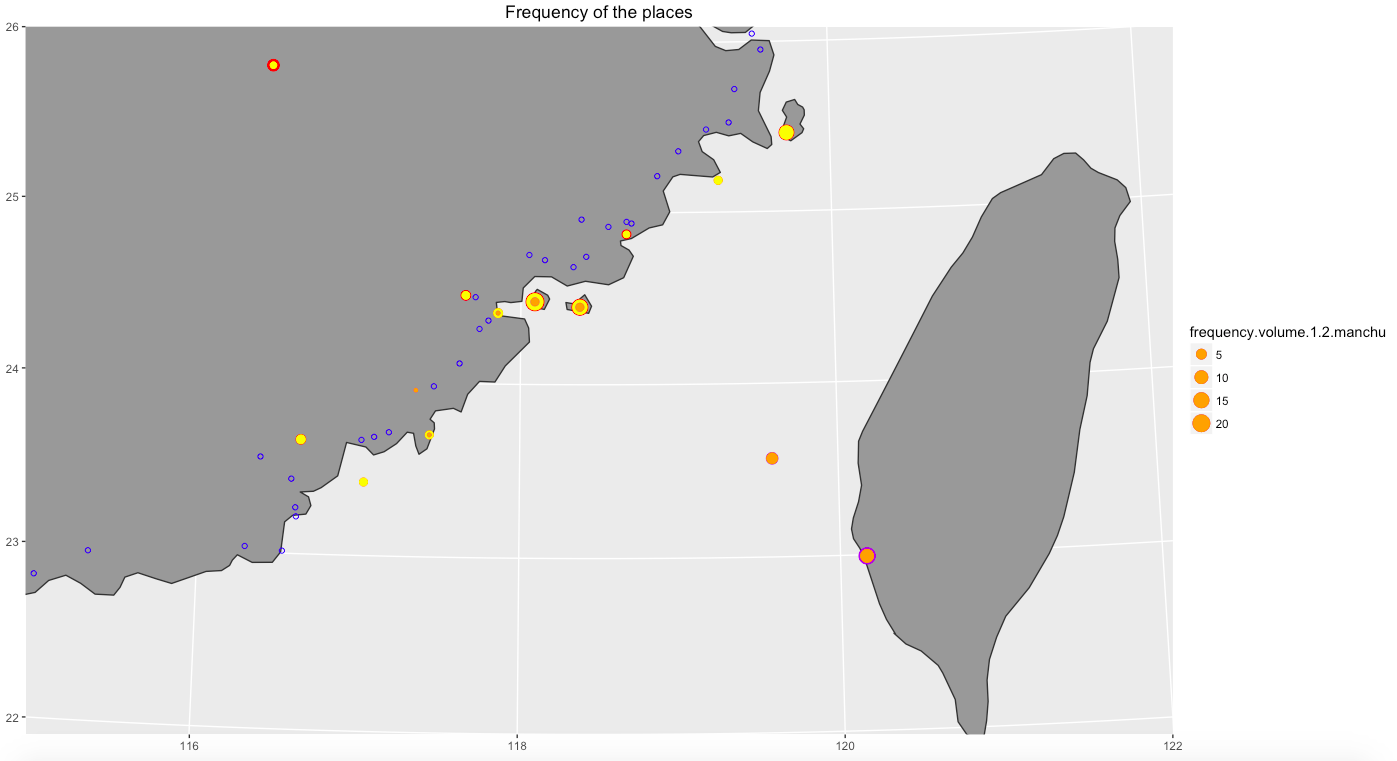

Map 7: The frequency of places in the Manchu language and Chinese under the repealed Coastal Exclusion Policy

Map 8 is mixed Map 1 to 7. It might suggest and support my argument in previous paragraph. Therefore, I can certainly be confident to argue that the Manchu language was more precise, detailed, and direct to mentioned the name of places than in Chinese because the government did not reveal the failure of processing the Coastal Exclusion Policy. Although the failure of the Coastal Exclusion Policy was widely known in Fujian, it was not recognized in other provinces and non-China regions, such as Mongolia and Tibet. Because the main purpose of editing this book is to proclaim the imperial prestige and success, the government had to carefully control the content. The threshold of learning the Manchu language was higher than learning Chinese because the Manchu language was only used in high class. In contrast with the Manchu language, Chinese had been the dominant language for over two thousand years. The failure of the Coastal Exclusion Policy could be limitedly recognized by ruling class, but this could not be known by Chinese folks.

Map 8: The frequency of places in the Manchu language and Chinese under the Coastal Exclusion Policy in the first three volumes

4. Conclusion

According to the approach of the digitial humanities, conducting text mining to compare two different languages of the same book suggests that the Manchu language or Chinese text was not the copy or translation version of the other. Moreover, the frequency of places in the Manchu language is slightly more precise than Chinese version. Moreover, because the historical background, the frequency of places in this book might be highly related to the imperial policy, the Coastal Exclusion Policy. In fact, combining the text mining and spatial history, it shows how the government controlled texts to limit folks to recognize the failure of the Coastal Exclusion Policy.

Admittedly, I can read the Manchu language and Chinese. Frankly, before I used the approach of the digital humanities to analyze these two texts, I believe that the two texts in fact were exactly the same although I’m a follower of the New Qing History, which means that I did not believe the Manchu language sources were translated from Chinese sources. However, in this case, for me, there was probably a main draft or main author, and the two texts were just edited from the main draft. However, because of the difference between the frequency of places, I change my mind. Also, this enhances the idea of the New Qing History: the Manchu language and Chinese sources should be equally emphasized in order to establish a broader Qing history.