Sehr Mehra

Professor Li & Ristaino

CHN375W/ITAL375W

26 June 2018

Tracing the Origins of the Noodle

Mix water and flour and knead into a dough, you now have a plethora of prospects in the palm of your hands. Noodles are the epitome of versatility and flexibility, and it’s this adaptable nature that has contributed to its rise as a world renowned food. Noodles are eaten as pho in Vietnam, chow-chow in Nepal, seviyan in India and many other permutations and combinations throughout the globe. While the popularity of noodles is a widely accepted consensus, its origin is still a prominently debated subject. There are numerous contenders who have claimed to be the creators of the Noodle. Italians profess that they are the pioneers of this plant based food, whereas the Chinese argue that they invented this culinary sensation. In this paper I will endeavor to trace the geneses of this cereal food and subsequently attempt to end the age old dispute surrounding it.

We begin our historical research in the East Asian country, China. Noodles are believed to have originated here, as ‘Bing’, during the early rule of the Han Dynasty. They were then diversified by experimentation and the evolution of additional shapes and cooking methods. Noodles further gained cultural prominence via folklore related to ‘health, religion, economy’ and with the emergence of Chinese superstitions. (Zhang and Ma, 2016)However, due to recent archeological discoveries it’s likely that noodles were around much prior to the rise of the Han Rule. Excavation sites have revealed that wheat grains and early production apparatuses existed from the early to late Neolithic period – an astounding ten thousand years before now. More tangible evidence, which testifies to the existence of Noodles well into the past, was unearthed in 1999. ‘Noodles discovered among relics at the Lajia archeological site in Minhe County, Qinghai Province’. After radio-dating ‘the noodles and bowl of noodles’ found at the site, it was disclosed that they were crafted and cooked four thousand years ago during the early Xia Dynasty. These archaeological findings thus provide us with physical evidence which date back to periods long before the present day. They reveal that the noodle has been closely interwoven into the Chinese society and their culinary practices for eons. (Wei et al., 2017)

Noodles and noodle bowl discovered at Lajia archaeological site in 1999.

Noodles and noodle bowl discovered at Lajia archaeological site in 1999.

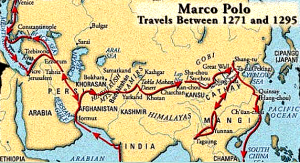

We now move on to our next destination in this culinary dissertation, Italy. Pasta is an integral part of the Italian diet and culture. With shapes ranging from small pinwheels to large sheets, its diversity can be witnessed across the regions of this unified country. Each Italian province has its own rich history with pasta, shaped by its geographical limits and foreign influences, and as a result unique dishes native to these expanses have become a beacon for their identities. The emergence of Pasta in Italy was formerly attributed to Marco Polo, a venetian explorer. He voyaged to China, and upon his return in 1295, he brought back copious amounts of spices and other discoveries which included noodles. (Jackson, P. 1998) However, there is a lot of opposition to this assertion as evident in the following remarks made by Justin Demetri in his article ‘The History of Pasta – Pasta through the ages’. ‘Well, Marco Polo might have done amazing things on his journeys, but bringing pasta to Italy was not one of them: noodles were already there in Polo’s time.’(Demeteri, 2018)

Map outlining Marco polo’s travels from Venice to China.

Map outlining Marco polo’s travels from Venice to China.

One of the leading counter arguments was that pasta already existed during the Roman-Etruscan era as ‘Lagane’. This view is supported by the words of the famous Roman poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus, commonly known as Horace, who wrote ‘I come back home to my pot of leek, peas and laganum’. He wrote the above mentioned to defend himself against allegations that he was trying to fit in with members of the ‘higher society’. This modest meal of pasta and vegetables were meant to portray his own humble nature. While it’s not known if these verses were successful in gaining Horace’s innocence, it’s certain that they are one of the oldest mentions of the Italian Pasta amongst literary works. (Ullman, n.d.) Horace wrote his first book around thirty-four BC, which makes it about two thousand years old. Something interesting to note here, is that the pasta, made by mixing various cereals and water, available during the Etrusco-Roman era was oven baked and not boiled. To advance the point pertaining to the prevalence of pasta in ancient times we can take Apicius’s example. He too was a Roman author, who discussed a recipe of ‘laganon’ in his discourse published in the first century AD. (Food-info.net, 2018) These written accounts date back thousands of years. Pasta has thus been a component of the Italian diet for centuries.

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) – Roman Lyric Poet.

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) – Roman Lyric Poet.

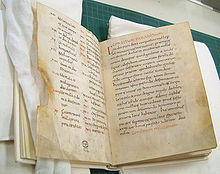

Apicius – collection of Roman recipes, published in the 1st century AD.

Apicius – collection of Roman recipes, published in the 1st century AD.

Another theory set forward maintained that the Arabs played a role in the development and spread of boiled noodles or ‘itriyah’. They significantly influenced Italian food and culinary practices when they invaded the country in the 8thCentury AD. Their cuisine and culture was adopted in regions such as Sicily, where the spread of sweet and savory foods such as pasta con la sarde was observed after the Arabic conquest. Macaroni too, gained widespread admiration amongst the Sicilians at this time. (Italy’s Culinary Heritage, n.d.) Charles Perry an American Historian who specializes in mapping the origin of the pasta said the following words ‘…the first clear western reference to boiled noodles is in the Jerusalem Talmud of the fifth century AD written in Aramaic for which the term ‘itriyah’ was used.’ He later goes on to say that during the 10thCentury ‘itriyah’ referred to dry noodles exclusively and didn’t include the fresh ones. (Giacco, 2016)The Talmud additionally discussed the term ‘rihata’ which referred to boiled flour and honey which later gave rise to the word ‘rishta’ which translates to noodles. The term ‘rihata’ has been talked about and mentioned in scholarly works since ages. The Arabs thus have a considerable assertion that they played an important role, which resulted in the dominance of pasta in the diets and hearts of the Italian people. (Cooper, 1935)

Itriyah – pasta as mentioned in the Talmud.

Itriyah – pasta as mentioned in the Talmud.

Rishta (Pasta) cooked with lentils and caramelized onions.

Rishta (Pasta) cooked with lentils and caramelized onions.

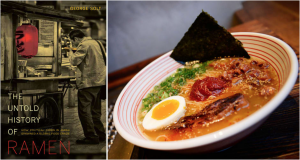

Moving further east from China, we now travel to Japan. Ramen is not only a culinary phenomenon here; it is a cultural marvel as well. Japan has museums dedicated to this fast-food, ramen stalls throughout the country, and television cooking shows fashioned around this spicy broth with noodles. The widespread consumption of Ramen by the residents of Japan is unparalleled by any other people. These facts beg the question ‘who are the ancestors of these instant noodles’ ‘was there a Japanese predecessor to this curried noodle dish’. On further research it becomes clear that ramen was introduced to Japan in the form of noodles, from China. Chinese chefs, who migrated to Japan, began working and cooking meals featuring noodles at local restaurants. These foods then gained extensive fame and were regarded in high esteem by the citizens of Japan. They had built an appetite for the food, which could only be satiated by mechanizing the industry. Ramen, in present day, has become a national staple food in post-war Japan. Even though noodles weren’t devised here, they have become a vital part of the country’s national identity and the favorite grub of its people. (Solt, 2014)

The Untold History of Ramen – Book by George Solt, which aims to answer the following question ‘How did ramen become the national food of Japan?’

The Untold History of Ramen – Book by George Solt, which aims to answer the following question ‘How did ramen become the national food of Japan?’

Now we’ll analyze the influences of the Greeks on Italian foods, and more importantly pasta. These Mediterranean individuals and their practices induced changes in the regional cuisines of Italy, such as in Puglie where Greek food flourished. There was little meat in this region which was compensated by the use of fine sausage products and cheeses. (Italy’s Culinary Heritage, n.d.) When it comes to pasta there is a legend that speaks of its production and history. A Greek woman Talia, became the muse of a man named Macareo. She is alleged to have inspired him to create an iron machine, that could produce long strands of pasta, to feed starving poets. This discovery then remained a secret for several years, until shared with the founder of Naples in the sixth century BC. Utensils used for making pasta were also uncovered around about the fourth century BC. These were found in a tomb in Rome, and the carvings later proved that they belonged to the pre-Etruscan era. These utensils, thus signify that pasta making has been taking place in the history of Italy for an extended period of time. (Shelke, 2016)

The legend of Talia and Macareo outlined in the restaurant, Da Vinci’s, menu.

The legend of Talia and Macareo outlined in the restaurant, Da Vinci’s, menu.

After tracing the origins of pastas from countries all over the world, I think the most plausible birthplace of the noodle is China. This Asian country has the most promising data to support its claim of being the ‘inventors’ of this simple wheat and water based dough. The discovery of the noodle remains and bowl occurred two thousand years prior to Horace’s mentions of the ‘lagane’. With its physical, archeological evidence predating even the written records of Italian, Arabic and Mediterranean pasta, it truly does make China victorious in the contention. However, even though China maybe the site of the first instances of noodles and they may have introduced some countries like Japan and India to them, this doesn’t necessarily mean that they were the ones who introduced the rest of the world to it. Italians were enjoying pasta long before Marco Polo brought back the secrets of the Chinese noodle trade. As there is very little documented data and only a few preserved artifacts related to Italian pasta, it’s not right to make any broad claims about its beginning. It is also plausible that pasta developed spontaneously in China and Italy at different time periods. New evidence is bound to be unearthed at some point in the future, which will give more concrete and reliable sources with information about who introduced the Italians to the noodle.

I personally think noodles are united in their use of flour and water, however, every country takes this dough and molds it according to its own history, culture and terrain. Every noodle is thus separate from the other and there is no single category that these noodles lie in. In conclusion I would like to propose the following theory – there is no one ‘true’ inventor of the noodle, it is a world food which is continuously modified and customized via interactions amongst nations, ingredients and people.

Bibliography:

- Zhang, N. and Ma, G. (2016). Journal of Ethnic Foods.

- Wei, Y., Yingquan, Z., Liu, R., Zhang, B., Li, M. and Jin, S. (2018). AACCI Grain Science Library. [online] Aaccipublications.aaccnet.org. Available at: https://aaccipublications.aaccnet.org/doi/pdf/10.1094/CFW-62-2-0044 [Accessed 26 Jun. 2018].

- Jackson, P. (1998). Marco Polo and His ‘Travels’. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies,61(1), 82-101. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00015779

- Demetri, J. (2018).History of pasta. [online] Life In Italy. Available at: https://www.lifeinitaly.com/food/pasta-history.asp [Accessed 26 Jun. 2018].

- Ullman, B. (n.d.).Horace and the History of the Word Laganum. [online] Journals.uchicago.edu. Available at: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/359712 [Accessed 27 Jun. 2018].

- Food-info.net. (2018).Food-Info.net> History of Italian-type pasta.. [online] Available at: http://www.food-info.net/uk/products/pasta/history.htm [Accessed 27 Jun. 2018].

- Italys Culinary Heritage. (n.d.). .

- Giacco, R. (2016).Pasta: Role in a Diet. [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marilena_Vitale2/publication/301702419_Pasta_Role_in_Diet/links/59ce1321a6fdcce3b34b7831/Pasta-Role-in-Diet.pdf [Accessed 27 Jun. 2018].

- Cooper, J. (1935).Eat and be Satisfied. [online] Google Books. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ld7fuK6peH8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&dq=jewish+food+noodles&ots=eV_DDMWL1B&sig=r_vUL96-l2pC7MRKD-9lnZ_D62M#v=onepage&q=noodles&f=false [Accessed 28 Jun. 2018].

- Solt, G. (2014).The Untold History of Ramen. [online] Google Books. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=TaowDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR13&dq=noodles+in+japan+history+&ots=Yw_Bgo0RJ9&sig=Frch3-upTNheg4wHZ2vOlPi05B0#v=onepage&q=noodles%20in%20japan%20history&f=false [Accessed 28 Jun. 2018].

- Shelke, K. (2016).Pasta and Noodles. [online] Google Books. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=G5qRDQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT7&dq=itriyah&ots=QETKWXKpnJ&sig=nuIxfcADAxCPOSf2WurYndElFEU#v=onepage&q=itriyah&f=false [Accessed 29 Jun. 2018].