Atlanta Shape Change and Automobile

During the nineteenth century, Atlanta’s geographic expansion was largely due to the influence of the railroad. Its grid street pattern was radiated on a perpendicular plane from the railroad tracks in the down-town business district.

In 1874, the Atlanta Boundary was enlarged by 1/2 mile. Its configuration remained circular.

In 1889, Atlanta’s Boundary was enlarged by 1/4 mile. It broke the traditional concentric pattern of growth and included Inman Park, a planned residential suburb.

In 1895, Atlanta expanded to the east beyond Inman Park to the Dekalb County line, to the north at Highland Avenue and to the west to include West End.

By 1903, Atlanta’s 11 square mile land area was roughly 4 times as small as the size of Boston and an incredible 30 times smaller than New York.

At the turn of the century Atlanta remained on a “walking city” scale, and city administrators paid more attention to the construction and maintenance of sidewalks than streets.

In 1904, Atlanta spent $14,803.16 for the construction of 0.33 miles of streets and $34,752.08 for 6.11 miles of sidewalks. Before 1905 there were more paved sidewalks in the Georgia capital than paved streets.

Between 1900 and 1930, radical changes in Atlanta’s form, fabric, and physical character began to occur. One of the forces was the automobile.

1909 was the inaugural Automobile Week in Atlanta, the first automobile show in the South. The number of automobiles licensed grew from 99 in 1904-05 to 832 in 1908-09 and 1,628 in 1909-10. Automobile industrialists were convinced that the South was a target marketplace. The Piedmont Driving Club played a part in the rapid growth.

From July 1st 1909 to June 30th 1910, the number of automobile firms taking out annual business licenses in Atlanta grew by 35.

In 1910-1912, the condition of streets in Atlanta was questionable. The number of automobile dealers registered to do business in the city slipped from 44 in 1910-11 to 36 in 1911-12. 18 of the 44 were listed as out of business by the end of June 1911 and 10 more closed by the conclusion of the 1911-12 fiscal year. Questionable street conditions were evidenced by the “reliability tours” when contesting motorists found Georgia roads impassable. The Good Roads Movement between the late 1870s and the 1920s eventually improved the streets condition.

From 1912 to 1913, 3 automobile shows staged in Atlanta. Usefulness of motor vehicles encouraged better roads and greater business opportunities. By 1915, automobile licenses increased to 4,503 vehicles, and by 1920, 8,525.

In 1909-1920, Automobile-related jobs surged. Construction of new buildings began to house the incoming firms. In 1909, The Ford Motor Company decided upon Atlanta as the city to represent the Southeast branch.

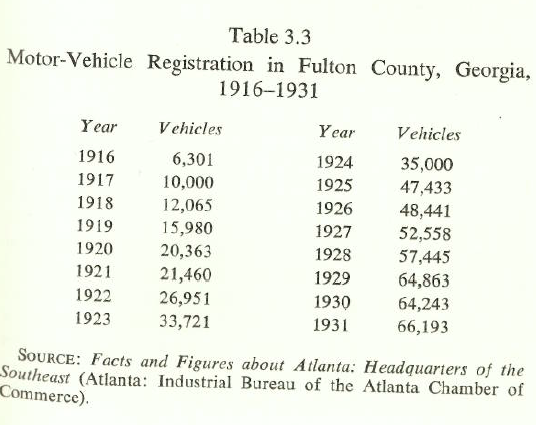

On April 10th 1949, Atlanta’s last streetcar was gone. Privately operated motorcars replaced the streetcar between 1920 and 1930. In 1920, 20,363 automobiles and trucks registered in Fulton County alone. Within 5 years this figure jumped to 47,433 and by 1930 it had grown to 64,243.

By 1930, many Atlantans who owned automobiles moved to new suburbs beyond the reach of streetcar service. The middle landscape between city and countryside gained popularity and the presence of automobiles and the economic prosperity of the twenties facilitated a suburban boom. Increased commercialization in the downtown area between 1910 and 1930 and a burgeoning population created a housing shortage which further generated demand for decentralized housing. With Jim Crow laws still in effect, whites were moving to the northside region while blacks were moving west. Between 1920 and 1929, Atlantans living outside the city limits had increased by 40,746 and by 1930 equaled 100,554 of Metropolitan Atlanta’s 370,920 population. That same year Atlanta achieved the rank of “Metropolis“: an urbanized area in which “all adjacent and contiguous civil divisions [had] a density of not less than 150 inhabitants per square mile.”

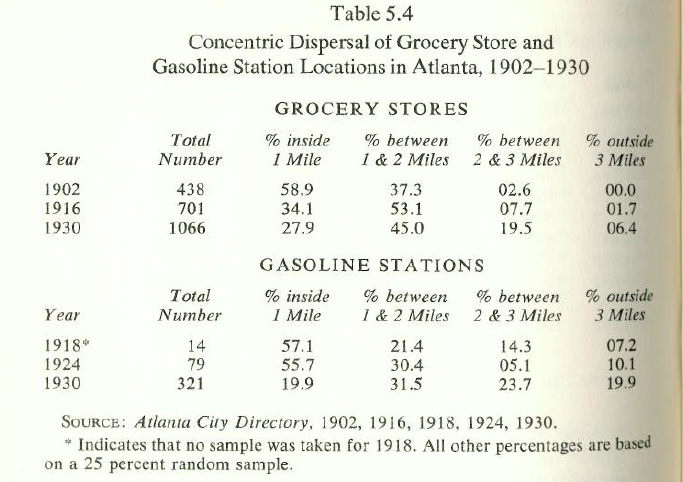

In 1900-1930, accompanying residential decentralization, businesses began a trend toward decentralization too. Atlanta’s thoroughfares that had been designed for railroads and major streets for automobiles now radiated at right angles from the railroad tracks. In the mid 1920’s traffic congestion was already a severe problem in downtown Atlanta. Facing traffic congestion, Preston Arkwright (power company and street railway company president) contended, “The streets should be opened up, narrow streets made wider.” Construction of Atlanta’s Motor Age viaduct commenced in late 1921 and many followed but the traffic situation continued. Restrictive parking along the streets in downtown was enacted. The traffic and the parking limitations placed a strain on retail business in downtown and the establishment of retail businesses in the suburban were pronounced during the 1920s. Retail subcenters were the forerunners of outlying shopping centers nowadays. In 1902, 96.2% of all grocery stores in Atlanta were located within 2 miles of the center of the city and only 2.6% could be found more than 2 miles from the center Atlanta. In 1930, only 27.9% of the grocery stores in the city within the 1 mile radius while the number was 58.9% in 1902.

By 1929, the completion of the Central Avenue and Pryor Street viaducts transformed Atlanta’s central business district from a railroad center into an oasis for automobiles. In the twentieth century, Automobiles became Atlantans’ primary means of transportation. The first paved highway nationally linking North and South, Dixie Highway (predecessor of I-75) was constructed and opened in 1929. Years later, Atlanta would later become the crossroads of the Southeast–the point at which converged 3 major southeastern interstate highways-I-20, I-75, and I-85.

Between 1920-1930, the growth rate of the land area outside the corporate limits of Atlanta was almost twice as great as the city itself. Growth and expansion became the Atlanta Spirit. Atlanta, however, was at the verge of losing population as outlying metropolitan districts pay lower property taxes and had a steady increasing property value. 1900, property values were highest along streetcar routes but by 1930 the automobile’s use changed this pattern and previously remote land witnessed increased demand and subsequently skyrocketed property values. The government was challenged to deliver services like police, fire, public health etc. to unprepared previously rural counties while having little tax support from unincorporated areas. A 1937 National Municipal League Study revealed, “Atlanta tax -payers pay five-sixths and outside Atlanta county taxpayers, one-sixth.” The imbalance led to establishment of a larger metropolitan unit of government that would be responsible for new suburban residential contingent. “Greater Atlanta” was created. The goal of a “greater” city was achieved.

During the nineteenth century, while prosperous, planning and constructions were private effort.

Atlanta’s suburban pattern of thoroughfares evolved illogically and with little or no relationship to the already existing street network. As automobile ownership increased and suburban life-style became more and more affordable, the same same traffic-choked thoroughfares in downtown Atlanta during the 1920s and early 1930s became evident in suburbs. “Jim Crowism” quickened by automobile and twenties sprawl result in a city more segregated by race than ever before.

Whites dominated the “garden suburbs” in the north and blacks in the western part.

Late 1940s and early 1950s – the first leg of metropolitan expressway system for Atlanta was constructed to serve the north side but bisected by that system were neighborhoods in other parts of the city like the Auburn Avenue district–the original center of black life in Atlanta–and the Grant Park neighborhood, both of which were inhabited by less influential citizens of the city.

In the 1960s, the area immediately south of Atlanta was designated as the point at which I-20 and I-75 would converge. Private land development on the south side, between the highway interchange and Five Points were subsided. Private development followed the precedent set by the automobile businesses that located along Peachtree Street between 1910 and 1920. This trend of northward development continued until by the mid-1970s when all the prestigious suburban “office parks” had located in the north side.

The automobile has had a major influence on shape change of Atlanta between 1900 and 1930 and continues to impact the pattern of development decades after.

Sources:

Automobile Age Atlanta

The Making of a Southern Metropolis, 1900-1935

Howard L. Preston