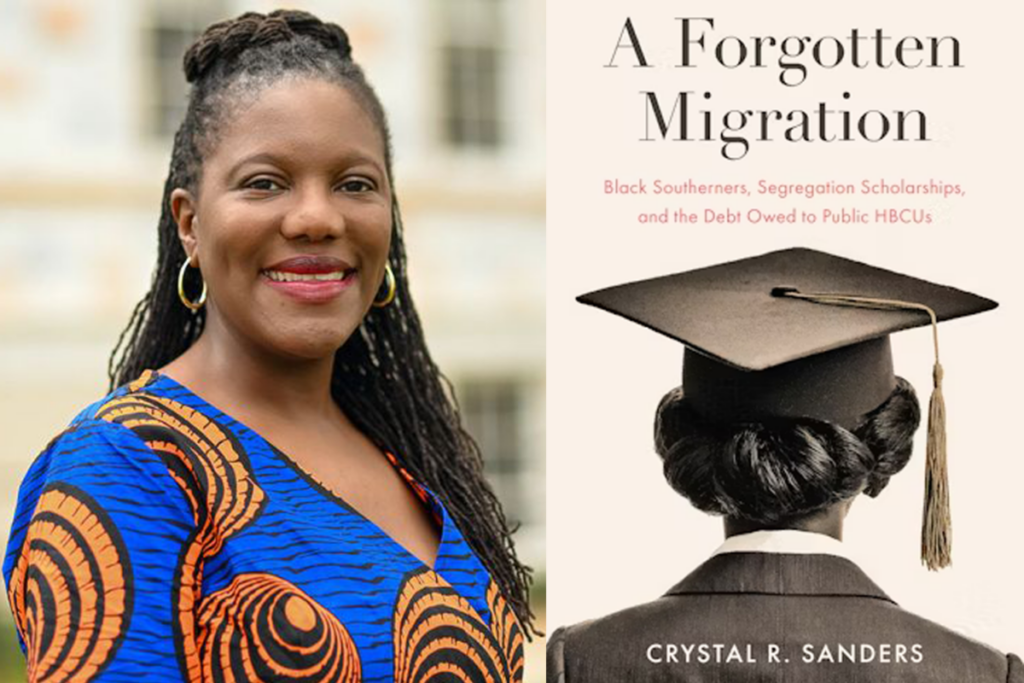

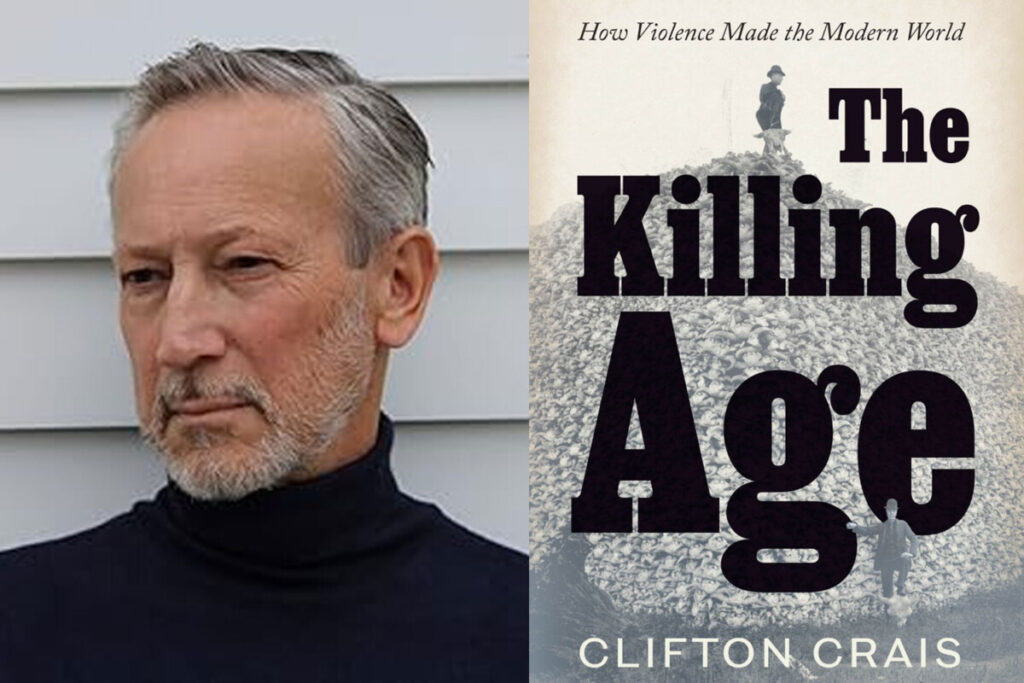

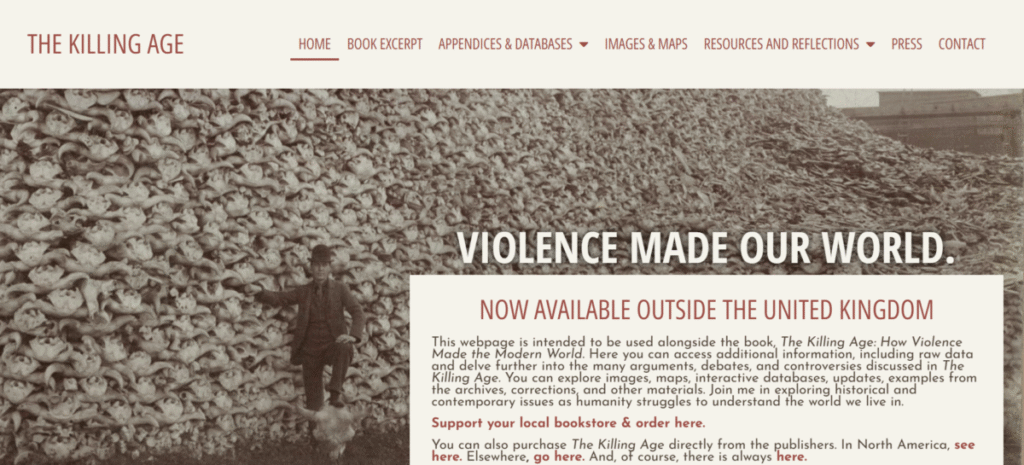

Dr. Clifton Crais, Professor of History, has published his most recent book, The Killing Age: How Violence Made the Modern World, with the University of Chicago Press. Crais foregrounds the role and significance of violence in the development of global capitalism from 1750 to the early 1900s, arguing that the period commonly described as the Anthropocene should, instead, best be understood as the Mortecene, or killing age. During this age, he writes, the new “ease and profitability of killing created a disturbing network of global connections and economies, eliminating tens of millions of people and sparking an environmental crisis that remains the most urgent catastrophe facing the world today.”

South African Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee offered the following praise for Crais’s book: “Synoptic in its reach, overwhelming in its detail, The Killing Age leaves one feeling like Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver, who came to prefer the company of peaceable horses to membership of humankind.”

In the Q&A below, Crais gives us a glimpse into the making of the monograph as part of the History Department’s New Books series.

Books are produced over years if not decades. Give us a sense for the lifespan of this book, from initial idea to final edits.

In some respects, The Killing Age returned me to questions I have been interested in since graduate school in the mid-1980s when books by scholars like Immanuel Wallerstein, Eric Wolf and others called attention to the importance of understanding the world economy and the development of capitalism. But it was only about a decade ago when I decided it was time to undertake a new project, partly inspired by a graduate course Mark Ravina and I taught on comparative empire. I became convinced that the literature on the Anthropocene was inadequate or at least incomplete and that, more generally, we had a poor understanding of the role of violence in the development of capitalism and the making of our contemporary world of planetary peril.

The research, writing and publication took about eight years. There was a lot of climate science and environmental history I had to first learn, and I had to decide on which archives I would delve into. I spent lots of time in England, but also many places across the United States. So, it took longer to research and write than previous books. Plus, The Killing Age is hefty, over 700 pages long, plus an associated website, thekillingage.com.

What was the research process like?

The Killing Age was by far the most difficult project I have undertaken. I had never done research in the histories of South America, Asia, and especially the United States. I also relied on multiple databases, some massive. The total amount of data I have stored and used for the project is more than 1 terabyte, in other words more than a million pages. One of the biggest challenges was how to navigate all the material while producing a book that is narratively driven and accessible to the general public. I ended up going through more than a dozen drafts.

Are you partial to a particular chapter or section?

I was originally trained in the history of Africa, so the chapters covering this part of the world had a certain familiarity; not so with other regions, including the United States. I am partial to the section “The American Ways of Killing” that explores the hunting of whales, beaver, and bison and its connections to economic change and the emergence of the US as a global power. Just learning about the entwined histories of humans and non-humans was fascinating, especially as I wrote some of these chapters during COVID-19.

How does this project align with your broad research agenda (past, present, or future)?

The Killing Age is both a kind of culmination and a departure. I have been thinking about many of the issues I explore for decades. At the same time, the project has convinced me of the importance of writing a global history of the twentieth century, about the possibilities of human progress and how these possibilities were so often subverted. In my next project I will be returning to the issue of violence and especially the redemocratization of the means of destruction, particularly after 1945.