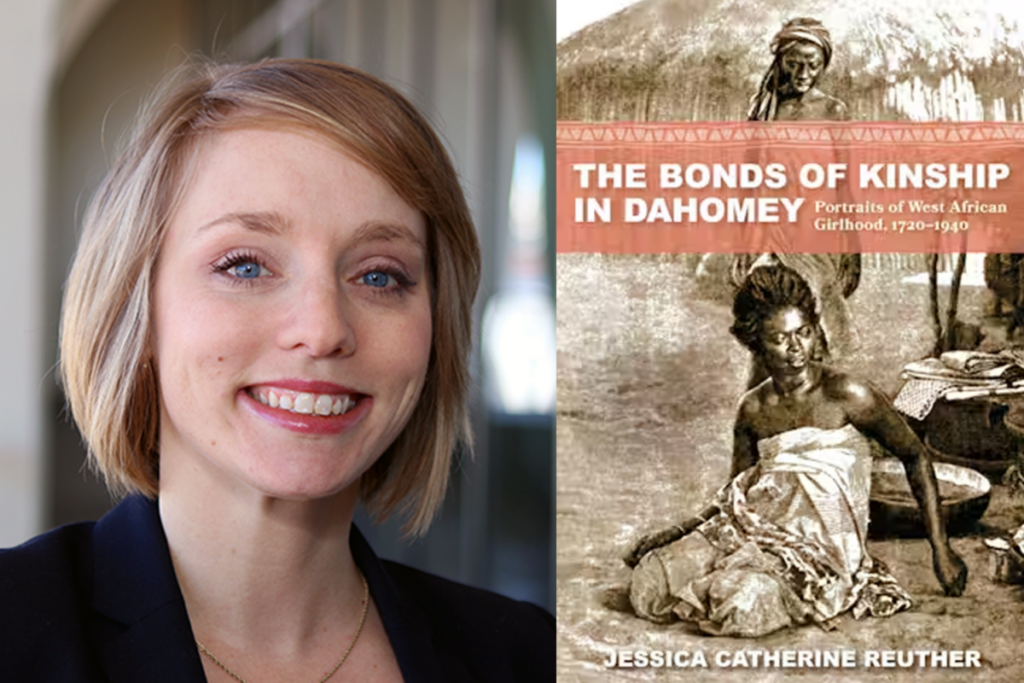

Dr. Jessica Catherine Reuther, a 2016 graduate of the doctoral program and Associate Professor of History at Ball State University, has published her first book, The Bonds of Kinship in Dahomey: Portraits of West African Girlhood, 1720–1940 (Indiana University Press, 2025). Relying on research throughout the world – from Benin, Senegal, France, and Switzerland to the United States – The Bonds of Kinship in Dahomey examines the common practice of girl fostering, or “entrusting,” in the kingdom and later colony of Dahomey (now the Republic of Benin) from 1720 to 1940. Reuther’s book draws from her dissertation, “Borrowed Children, Entrusted Girls: Legal Encounters with Girlhood in French West Africa, c. 1900-1941,” which was advised by Dr. Kristin Mann, Professor Emerita.

Read the abstract of The Bonds of Kinship in Dahomey below and consider purchasing a discounted copy during Women’s History Month from IU Press with code U25WHM (discount is 40%).

From the 1720s to the 1940s, parents in the kingdom and later colony of Dahomey (now the Republic of Benin) developed and sustained the common practice of girl fostering, or “entrusting.” Transferring their daughters at a young age into foster homes, Dahomeans created complex relationships of mutual obligation, kinship, and caregiving that also exploited girls’ labor for the economic benefit of the women who acted as their social mothers.

Drawing upon oral tradition, historic images, and collective memories, Jessica Reuther pieces together the fragmentary glimpses of girls’ lives contained in colonial archives within the framework of traditional understandings about entrustment. Placing these girls and their social mothers at the center of history brings to light their core contributions to local and global political economies, even as the Dahomean monarchy, global trade, and colonial courts reshaped girlhood norms and fostering practices.

Reuther reveals that the social, economic, and political changes wrought by the expansion of Dahomey in the eighteenth century; the shift to “legitimate” trade in agricultural products in the nineteenth century; and the imposition of French colonialism in the twentieth all fundamentally altered—and were altered by—the intimate practice of entrusting female children between households. Dahomeans also valorized this process as a crucial component of being “well-raised”—a sentiment that continues into the present, despite widespread Beninese opposition to modern-day forms of child labor.