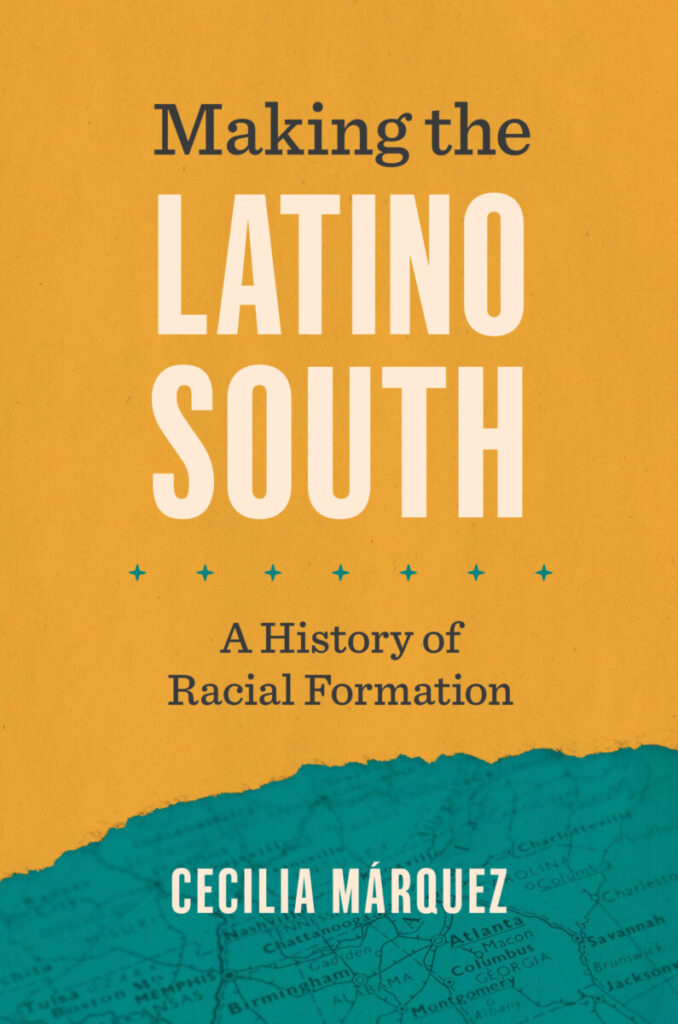

Dr. Iliana Yamileth Rodriguez, Assistant Professor of History, recently published a review essay in the Emory-based journal Southern Spaces about the state of research on Latinx histories in the U.S. South. Rodriguez’s piece analyzes how two recent books – Cecilia Márquez’s Making the Latino South: A History of Racial Formation (2023) and Sarah McNamara‘s Ybor City: Crucible of the Latina South (2023) – expand simplistic and sometimes exoticizing narratives about Latinx populations in the “Nuevo New South.”

Rodriguez is a historian of US Latinx communities with an emphasis on the US South. Her research examines Latinx experiences in relation to culture, race, ethnicity, labor, and migration. Her current book project, “Mexican Atlanta: Migrant Place-Making in the Latinx South,” traces the history of Metro Atlanta’s ethnic Mexican community formation and broader Latinx connections beginning in the mid-twentieth century.

Read an excerpt from Rodriguez’s Southern Spaces essay below along with the full article here: “Race & Gender in the Latinx South: A Review of Cecilia Márquez’s Making the Latino South & Sarah McNamara’s Ybor City.”

“Márquez and McNamara held a roundtable discussion at the 2023 Southern Historical Association meeting in Charlotte about the shifting terrain of Latinx history. Márquez made a key aspect of Latinx history clear: “when and where you are Latino matters.” Later in the same session McNamara added that, along with generational cohorts, “migration patterns matter.” With the various Latinx migrations to/through southern spaces since the late nineteenth at top of mind, the discussion highlighted the nuances of writing Latinx history from a southern vantage point. The conversation illuminated Chicana historian Vicki Ruiz’s argument that “region is intricately tied to Latina identity.” With attention to geographic and temporal specificities, Márquez’s Making the Latino South and McNamara’s Ybor City each demonstrate how Latina/o/x individuals, families, and communities navigated, understood, and claimed southern spaces over time. With their critical attention to the importance of regional racial formations, histories of racial capitalism, and the varied dimensions (racialized, gendered, generational) of Latinx identities and community formations, Márquez and McNamara have each made contributions that enrich more than two decades of scholarship.”