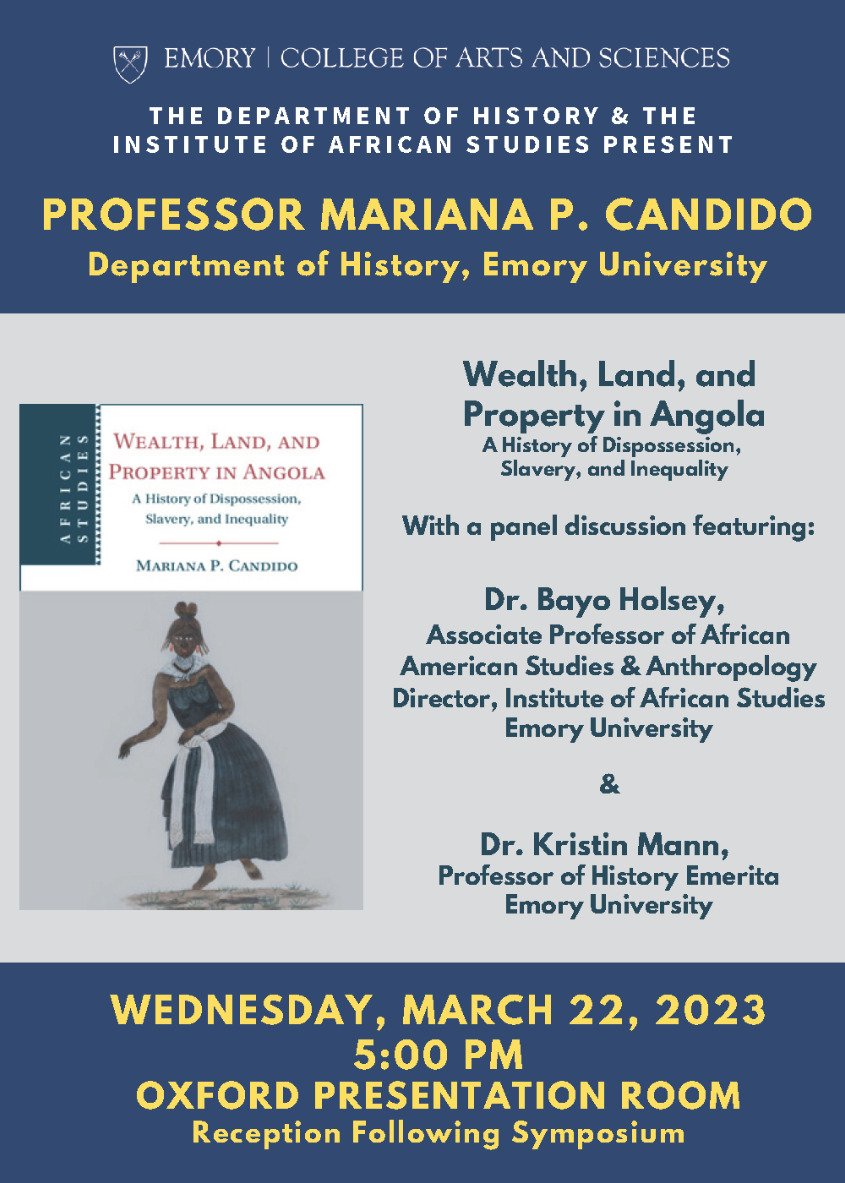

The History Department and Institute of African Studies are hosting a symposium centered on Dr. Mariana P. Candido‘s newest book, Wealth, Land, and Property in Angola: A History of Dispossession, Slavery, and Inequality (Cambridge UP, 2022). A panel discussion featuring Dr. Bayo Holsey, Associate Professor of African American Studies & Anthropology and the Director of the Institute of African Studies, and Dr. Kristin Mann, Professor of History Emerita, will follow a presentation by Dr. Candido. The event will take place on Wednesday, March 22, 2023 at 5pm in the Oxford Presentation Room. Find out more details about the event here, and read a recent Q&A about the book that Dr. Candido participated in for the History Department website: “New Books Series: Q&A with Mariana P. Candido about ‘Wealth, Land, and Property in Angola.’”

Category / Publications

Anderson Cited in ‘The Hill’ Piece on Voter Suppression

Dr. Carol Anderson was recently cited in an article written for The Hill and titled “GOP voter suppression measures are working, despite Democratic wins.” Written by veteran journalist Al Hunt, the op-ed discusses how Republican-led efforts to restrict voting access in recent years appear to be decreasing the number of votes cast, especially in states like Georgia and among Black and Hispanic voters. Hunt references Anderson’s chapter on voter fraud in the newly-released collection of essays Myth America: Historians Take On the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past (Basic Books, 2023). Read an excerpt from Hunt’s article below, along with the full piece.

Whether Georgia or elsewhere, the stated rationale is to “prevent fraud” — it’s just that when pressed, they can’t produce any. Ben Ginsburg, who for decades prior to Trump was the most prominent Republican election lawyer in America, suggests voting fraud is the “the Loch Ness Monster of the Republican party … People spend lots of time looking for it, but it doesn’t exist.”

This isn’t a new phenomenon. The 15th Amendment prohibited discrimination in the right to vote on the basis of race. After Reconstruction, southern segregationists found a new tact, writes Emory University historian Carol Anderson, in a chapter in a fascinating new book, “Myth America.”

Anderson writes: “The operatives and politicians camouflaged their discriminatory intent behind the charge of voter fraud to create the illusion that their primary concern was election integrity and democracy.”

Sound familiar?

“Carol Anderson’s journey to become a documentary filmmaker”

The Emory News Center recently published a Q&A with Dr. Carol Anderson about her experience creating the documentary film, “I, too.” Inspired by Langston Hughes’s poem of the same name, Anderson’s film engages with struggles for citizenship and democracy in America through three pivotal moments of racial and political violence: the Hamburg Massacre of 1876, the Wilmington Coup of 1898, and Ocoee Massacre of 1920. These historical events provide illuminating context for the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021 and its role in the history and future of American democracy. Anderson’s film premiered last fall at the Carter Center in Atlanta and has since been screened at Brandeis University and the Athens Democracy Forum in Greece. Read a quote from the Q&A with Dr. Anderson below, along with the full piece by the Emory News Center’s Susan M. Carini here: “‘I, too, am America’: Carol Anderson’s journey to become a documentary filmmaker.”

What is the genesis for “I, Too”?

The film is about patriotism and who is fighting for democracy. The folks who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 had a very narrow vision of democracy. They were trying to wipe out 81 million votes.

All the talk of the election being “stolen” centered on Atlanta, Milwaukee, Philadelphia and Detroit — cities with sizable Black populations. Those with that mindset were intentionally linking theft and criminality with urban areas. When I think about the Black citizens of this country, I see a group of people who have always fought for American democracy, even when it has not fought for them. So, my hope was to shine an honest light on this battle about American citizenship and democracy.

‘New York Times’ Reviews New Collection with Contribution from Anderson

Carlos Lozada, the nonfiction book critic for The New York Times, recently published a review of Myth America: Historians Take On the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past (Basic Books, 2023). Co-edited by Kevin M. Kruse and Julian E. Zelizer, the collection features a contribution from Dr. Carol Anderson, Charles Howard Candler Professor of African American Studies and Associated Faculty in the History Department. Anderson’s chapter debunks myths about the prevalence of voter fraud in U.S. elections and illustrates how such discourses have served to exclude and disenfranchise voters. Read an excerpt of the review below, along with the full article here: “I Looked Behind the Curtain of American History, and This Is What I Found.”

Several contributors to “Myth America” successfully eviscerate tired assumptions about their subjects. Carol Anderson of Emory University discredits the persistent notion of extensive voter fraud in U.S. elections, showing how the politicians and activists who claim to defend election integrity are often seeking to exclude some voters from the democratic process. Daniel Immerwahr of Northwestern University puts the lie to the idea that the United States historically has lacked imperial ambitions; with its territories and tribal nations and foreign bases, he contends, the country is very much an empire today and has been so from the start. And after reading Lawrence B. Glickman’s essay on “White Backlash,” I will be careful of writing that a civil-rights protest or movement sparked or fomented or provoked a white backlash, as if such a response is instinctive and unavoidable. “Backlashers are rarely treated as agents of history, the people who participate in them seen as bit players rather than catalysts of the story, reactors rather than actors,” Glickman, a historian at Cornell, writes. Sometimes the best myth-busting is the kind that makes you want to rewrite old sentences.

Billups Publishes Business History of Koinonia Farm in the ‘Journal of Southern History’

Doctoral candidate Robert Billups published an article in the Journal of Southern History, titled “The Cost of Civil Rights: White Supremacist Violence and Economic Resistance against Koinonia Farm during the Civil Rights Era.” The piece offers a unique look at Koinonia Farm, a Christian agricultural community founded in the post-WWII era in southwestern Georgia. By the mid-1950s, Koinonia Farm had grown into a large, self-sustaining interracial commune and commercial farm. Whereas most studies have emphasized the place’s religious and cultural life, Billups’s article offers a deep dive into the financial history of Koinonia, particularly how the farm survived a business climate hostile to its antiracist, pro-Civil Rights positions. Billups is completing his dissertation, “‘Reign of Terror’: Anti–Civil Rights Terrorism in the United States, 1955–1971,” under the advisement of Drs. Joseph Crespino and Allen Tullos.

Anderson Interviewed by ‘Washington Post’ about Contribution to New Book, ‘Myth America’

Dr. Carol Anderson was recently interviewed by Washington Post senior writer Frances Stead Sellers about her contribution to the book Myth America: Historians Take On the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past (Basic Books, 2023). Edited by Kevin M. Kruse and Julian E. Zelizer, the book aims to upend misinformed myths about American history that the editors see as taking strong root in contemporary popular discourse. Anderson’s chapter, “Voter Fraud,” addresses how misinformation about the frequency and threat of voter fraud have fueled practices of racialized voter suppression. Watch Anderson in conversation with Francis Stead Sellers here and read a excerpt from the transcript of their interview below. Anderson is Charles Howard Candler Professor of African American Studies and Associated Faculty in the History Department.

MS. STEAD SELLERS: Professor Anderson, you similarly give great historical context to voter suppression, talking particularly about 19th century Mississippi, but can you tell me whether you feel today is different, or are we reliving what you have observed and documented earlier on in U.S. history?

DR. ANDERSON: I’m going to say apocryphally, Mark Twain said history may not repeat itself, but it sure do rhyme. And we are in the rhythms right now. We are rhyming. And so part of what Mississippi did in 1890 was to say, oh, we don’t want Black folks to vote, but because of the 15th Amendment that says that the state shall not abridge the right to vote on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, then how do we write a law saying we don’t want Black folks to vote without writing a law saying we don’t want Black folks to vote? And Mississippi said, “Got it. What we’re going to use is to use the legacies of slavery and make those legacies of slavery, like poverty and illiteracy, the access to the ballot box. And so you get a poll tax, and you get a literacy test, and you get a Supreme Court that blessed both of those policies on high, and that led to this massive disfranchisement of Black folks that you saw in the South with the poll tax and the literacy test.

Now you think about what happened in the U.S. after Shelby County v. Holder, whereas the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 gutted the Voting Rights Act, the pre-clearance provision of the Voting Rights Act, and you had these states implement these policies that on its surface looked race neutral, like voter ID. But in fact, they were racially targeted.

These state legislatures went through, and they looked at, by race, who had what types of government-issued photo IDs and then made the ones that Whites had the primary access to the ballot box.

In Alabama, for instance, they said you must have government-issued photo ID, but your public housing ID does not count for access to the ballot box. Now that looks like race neutral, except 71 percent of those who had public housing IDs in Alabama were African American, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund found that for many, it was the only government-issued photo ID that they had.

And also note that what they used, just like Mississippi in 1890, was the language of “cleaning up” the ballot box, “ending corruption” at the ballot box. We must have “election integrity,” except just like in Mississippi in 1890, there wasn’t the kind of individual voter fraud that could change an election that we’re seeing, that we were seeing back then.

Andrew G. Britt (PhD, ’18) Publishes Article in ‘Journal of Latin American Studies’

Dr. Andrew G. Britt, a 2018 alumnus of the History doctoral program, recently published an article in the Journal of Latin American Studies. Titled “Spatial Projects of Forgetting: Razing the Remedies Church and Museum to the Enslaved in São Paulo’s ‘Black Zone’, 1930s–1940s,” the piece excavates the history of the former headquarters of Brazil’s Underground Railroad and a longtime museum to the enslaved. The article emerged out of Britt’s dissertation, which was advised by Drs. Jeffrey Lesser and Thomas D. Rogers. Britt is Assistant Professor of History and Digital Humanities at the UNC School of the Arts. Read the abstract of the article below along with the full piece.

“In the shadows of a Shinto torii (gateway) in São Paulo’s ‘Japanese’ neighbourhood rests the city’s first burial ground for enslaved Africans. Recently unearthed, the gravesite is one of the few visible remains of the Liberdade neighbourhood’s significance in São Paulo’s ‘Black zone’. This article excavates the history of the nearby Remedies church, the headquarters of Brazil’s Underground Railroad and a long-time museum to the enslaved. The 1942 demolition of the Remedies church, I argue, comprised part of a spatial project of forgetting centred on razing the city’s ‘Black zone’ and reproducing São Paulo as a non-Black, ethnically immigrant metropolis.”

The Feast of Words Event Celebrates Books by Emory Faculty, including Seven Historians

For the last 19 years the Center for Faculty Development and Excellence, Emory Libraries, and the Emory Barnes and Noble Bookstore have hosted the Feast of Words, an annual event to celebrate the Emory faculty members who have written or edited books in the prior year. The December edition of the festival featured 89 books, including seven by historians at Emory, published between September 1, 2021, and August 31, 2022. Read the titles of the books published by Emory historians below, along with the full list here: “Celebrating Faculty Authors.”

- Tonio A. Andrade. Het laatste gezantschap: De Nederlandse missie van 1795 en de westerse betrekkingen met China. Robert Vernooy, trans. Querido.

- Anthony A. Briggman (Theology) and Ellen Scully, eds. New Narratives for Old: The Historical Method of Reading Early Christian Theology. Essays in Honor of Michel René Barnes. Catholic University of America P.

- Adriana Chira. Patchwork Freedoms: Law, Slavery, and Race beyond Cuba’s Plantations. Cambridge UP.

- Astrid M. Eckert. Zonenrandgebiet. Westdeutschland und der Eiserne Vorhang. Thomas Wollermann, Bernhard Jendricke, and Barbara Steckhan, trans. Ch. Links.

- Daniel LaChance and Paul Kaplan. Crimesploitation: Crime, Punishment, and Pleasure on Reality Television. Stanford UP.

- Pablo Palomino. La Invención de la Música Latinoamericana. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Polly Price. Plagues in the Nation: How Epidemics Shaped America. Beacon.

Jessica Reuther (PhD, ’16) Publishes Article in the ‘Journal of African History’

Dr. Jessica Reuther, a 2016 graduate of the African history program, has published an article in the Journal of African History. Titled “Street Hawking or Street Walking in Dahomey?: Debates about Girls’ Sexual Assaults in Colonial Tribunals, 1924–41,” Reuther’s piece centers on sexual assault investigations in colonial Dahomey. Reuther’s analysis of those investigations reveals caregiving practices among older women for girls who suffered sexual assaults as well as the vulnerability of street hawkers to such assaults. Reuther is Assistant Professor of African History at Ball State University. Read the article abstract below.

Between the judicial reorganizations of 1924 and 1941, the colonial tribunals in Dahomey heard more than two hundred cases of rape. Teenage or younger girls engaged in street hawking were the most common victims of rape who reported their assaults to these tribunals. Many of the cases stand out because market women played the dominant role in transforming girl hawkers’ experiences of sexual assault into formal grievances. The history of sexual assault in colonial Africa has largely focused on how ‘customary’ and colonial courts have or have not punished the crime of rape. This approach privileges masculine authorities’ views of sex, consent, and gender violence. This article focuses on the investigative processes in cases of sexual assault. In doing so, two gendered histories emerge: firstly, a history of elder female caregiving to girls suffering the aftereffects of sexual assaults and, secondly, a history of the vulnerability of hawkers to quotidian sexual violence.

Doctoral Student Anjuli Webster to Present at Brown U. Workshop “Rivers on the Move”

History doctoral student Anjuli Webster was recently accepted to an international workshop at Brown University in June of 2023. Titled “Rivers on the Move,” the event will bring together environmental historians, hydrologists, and other historically-minded humanists and natural scientists to understand better how past and contemporary riparian change relate to social and political shifts, from economic development to legal frameworks. The workshop will result in an edited volume of interdisciplinary essays that aim to appeal to a wide range of riverine scholars and students. “Rivers on the Move” is organized by Bathsheba Demuth, Mark Healey, Giacomo Parrinello, and Larry Smith, with support from the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society, in collaboration with the project Shifting Shores, funded by an Emergence(s) grant of the City of Paris. Webster is currently conducting fieldwork for her dissertation, titled “Fluid Empires: Histories of Environment and Sovereignty in southern Africa, 1750-1900.”