During the fall of 2022, Mariana P. Candido, Adriana Chira, and Mariana Armond Dias Paes of the Max Plank Institute for Legal History received a three-year grant from Emory’s Office of the Provost. Titled “Land Dispossession, Inequality, and the Legacies of Slavery in Africa and Latin America,” the project is one of five that will receive a part of $1.4 million in support. The three historians will use the resources to conduct research, develop a digital platform, and initiate several pedagogical innovations focusing on land politics and sustainability in post-emancipation societies in Africa and Latin America. They will be engaging with primary sources located in endangered archives, including Cuba, Cape Verde, and Angola, while also developing new ways of sharing some of this material through public-facing platforms and new courses at undergraduate and graduate level.

The three project leaders point out that their work emerges from a belief that the humanities, and historical approaches in particular, are fields that are uniquely positioned to offer new ways of thinking about land dispossession, rural inequalities, and environmental sustainability. According to Candido, Chira, and Dias Paes, such approaches allow scholars to examine dispossession in the long term, exploring how present-day expulsion from the land is rooted in socio-economic structures dating back to slavery and colonialism. A humanistic approach to land dispossession also sheds light on alternative modes of community-building and property ownership that emerged from below that more quantitative social scientific approaches have ignored. Dias Paes emphasizes that “much of the legal framework of today´s legal system in what concerns property was created in the nineteenth century. Thus, if we want to reform these legal systems in the sense of shifting the current model of exploitation, we must discuss their roots and de-naturalize legal ideas such as ‘absolute ownership right,’ ‘legal personality,’ and so on.”

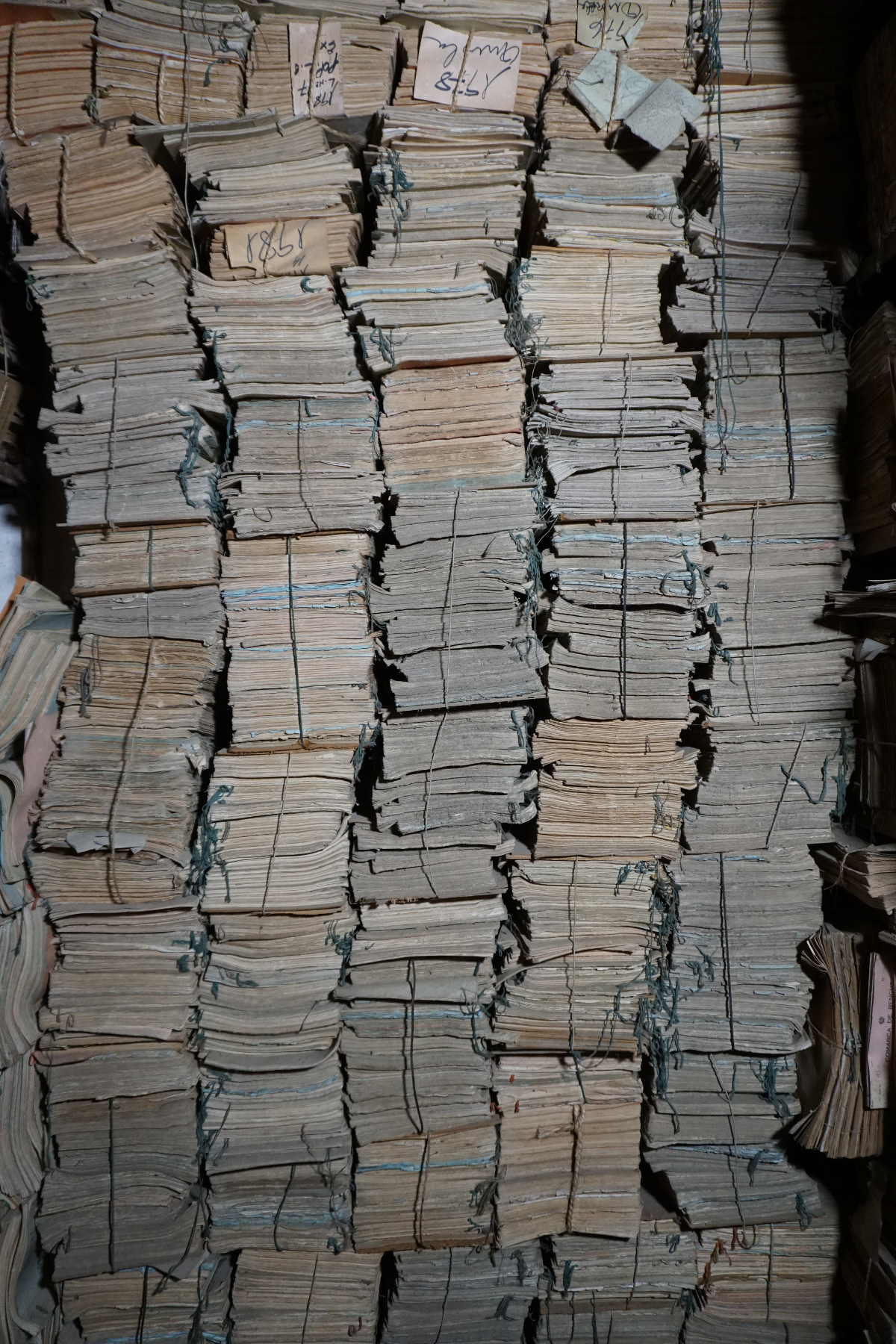

At the core of the project is a fundamental commitment to collaboration as a tool for writing and practicing better history. Candido and Chira are extremely excited to develop their collaboration with Mariana Dias Paes (with whom Candido has been working for a few years now), an ambitious visionary thinker in the field of legal history. Dias Paes is a Research Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory (Frankfurt am Main) where she heads the project “Global Legal History on the Ground: Court Cases in African Archives.” In the framework of the project, she has been digitizing over 30,000 court cases stored at the Cape Verde National Archives. Since 2017, together with Mariana Candido and Juelma Ngãla (ISCED-Benguela, Angola), she organized the court cases collection of the Benguela District Court (Angola). Her research focuses on the social and legal history of the South Atlantic (Brazil, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau), between the 17th and the 20th centuries. She has published extensively on issues pertaining to judicial disputes over land and labor in English, Portuguese, Spanish, and French. Her publications include: Esclavos y tierras entre posesión y títulos: la construcción social del derecho de propiedad en Brasil, siglo XIX (2021) and Escravidão e direito: o estatuto jurídico dos escravos no Brasil oitocentista, 1860-1888 (2019). She has also published articles in flagship journals such as Law & History Review, Atlantic Studies, Administory-Zeitschrift für Verwaltungsgeschichte. Since 2020, she serves as book review editor of the Journal of Global Slavery. She has been affiliated with international projects funded by the European Commission, the Max Planck Society, and CNPq/Brazil.

Dias Paes began researching the relation between law and slavery while she was in Law School. “It was during my masters, on freedom suits filed by enslaved people in Brazil, that I came to realize that the legal categories structuring these court cases and the legal arguments within them were the same ones used in land disputes. I decided to study this entanglement deeper during my Ph.D., and it became evident that the legal connection between property ownership and land ownership was mutually constitutive with broader economic and social relations. This was such a fascinating topic, that connected historiographical fields that do not often engage with each other, that I decided to pursue this topic further in the following years. For me, it is now clear that the history of slavery and land dispossession in the Global South is the basis of the current climate crisis.”

Asked to explain more about the collaborations that will emerge through the framework of this grant, Dias Paes said the project “will be fundamental to put my own individual research in perspective and access my results in a more complex fashion. When one is doing research individually, time and resources end up restricting the geographical and time scope of our work. Working collaboratively allows us to compare different contexts and thus understand with more complexity local process. Collaboration is fundamental to global and transnational research while allowing us to also conduct meticulous empirical research. Moreover, our project puts together researchers with different backgrounds, historians, and lawyers. This interdisciplinary collaboration will also deepen our debates and analysis. But our collaboration is not restricted to the project. We will also strengthen our partnerships with archival institutions in the Global South. In the age of digital humanities, it is urgent that we put forward debates on digital infrastructure and data sovereignty in Africa and Latin America. Digital humanities projects can both deepen the asymmetries between the Global South and the Global North or it can be an emancipatory tool, that broadens the access of Global South scholars to research infrastructures. Thus, we want our partnerships to be a laboratory on how to do digital humanities in the least asymmetrical way possible. Serious dialogue with our partners will be the key to achieving this goal.”

Learn more about the work of the three project leaders of “Land Dispossession, Inequality, and the Legacies of Slavery in Africa and Latin America” on their faculty pages: