Evolution of Chinese Noodles in NYC: A Tale of Immigration and Adaptation

By Dylan Z. Frank

From Lanzhou la mian to Sichuan dandan noodles and Beijing zhajiangmian to Fujianese ban mian, New York City is now home to a proliferation of different types of Chinese noodles across its three largest Chinatowns (Exhibit A). According to 2012 Census Estimates[1], New York City has an estimated Chinese population of 573,388, making it the largest metropolitan Chinese diaspora population in the world of any city outside of Asia. While it was Chinese immigration that first brought different types of Chinese noodles to New York City, media, the desire for novelty, and growing consumer acceptance of ethnic foods in America have also helped to propel the evolution and spread of Chinese noodle dishes far beyond NYC’s Chinatowns.

The story of Chinese noodles in New York City arose from immigration and the need for Chinese immigrants to make a living in their new country. Chinese immigration to NYC can largely be separated into four main waves: Cantonese (Late 1840s-1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, 1943-1950s (limited numbers), 1965-1980s), Taiwanese (1970s), Fujianese (1980s-Present), and Chinese from all parts of Mainland China (late 1960s-Present). Each of these waves of Chinese immigration brought different types of Chinese noodle dishes to NYC.

The first wave of Chinese immigration to the United States consisted predominately of working-class males from Guangdong (or “Canton”) Province who emigrated to the West Coast during the mid-1800s. The 1849 San Francisco Gold Rush and the 1863-1869 construction of the first Transcontinental Railroad were two events that provided Cantonese Chinese immigrants with an opportunity to escape from widespread poverty and political unrest caused by the Taiping Rebellion[2] back home, and this initial wave of Cantonese immigration to the West Coast continued on until the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Since Chinese immigrants to the West Coast often faced extreme anti-Chinese sentiment and employment discrimination upon coming to the States, many found themselves needing to establish businesses where they could be self-employed, including Chinese restaurants. These early Chinese restaurants cooked an Americanized version of Cantonese cuisine that catered to local tastes, with chop suey (translation: “odds and ends”) becoming the most popular dish. After the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, this version of Americanized Chinese food spread from the West Coast to New York City and eventually gave way to the invention of chow mein, the first Chinese noodle dish to emerge in NYC’s Chinese restaurants on a large scale.

According to Deh-Ta Hsiung’s book Food of China, “Chow Mein” is a romanization of the Taishanese word chāu-mèing, which means stir-fried noodles[3]. It first emerged in New York’s Mott Street Chinatown in the 1880s and coexisted alongside chop suey on many of NYC’s American-Chinese restaurant menus. While in some ways chow mein is similar to versions of stir-fried noodle dishes from Guangdong Province in China, its composition was modified to better suit American tastes and ingredient availability. For example, chow mein’s ingredients are effectively the same as chop suey’s except for the fact that chow mein is a noodle dish. The ingredients of chow mein that overlap with chop suey include onions, celery, and a sweet-tasting brown sauce made from a combination of soy sauce and corn syrup that was designed to suit the American palate[4]. In the below image of chow mein from Big Wong, one of Manhattan Chinatown’s oldest restaurants, we can see “Beef Chow Mein” pictured (Exhibit B). For this particular dish, most vegetables have been removed, possibly to better suit the tastes of Western consumers. Outside of chow mein and lo mein (the steamed version of chow mein), other types of Cantonese Chinese noodle dishes one can find in NYC Chinatowns included wonton mian and Clay Pot Noodles (pictured, Exhibit C). Cantonese also sometimes enjoy topping their noodles with BBQ roasted meats such as pork, chicken, or duck.

While the first wave of Chinese immigration to NYC was almost exclusively Cantonese, changes in immigration policies brought on by Lyndon B. Johnson’s Administration (mainly the passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965) led to a sharp increase in permitted Chinese immigration and fueled the arrival of a second wave of Chinese immigrants[5]. According to Time Magazine, this “liberalization of American immigration policy” led to the emergence of new types of Chinese cuisines in the United States from “areas like Hunan, Sichuan, Taipei and Shanghai.” Many Chinese who came to the States at this time were fleeing the Cultural Revolution, particularly so in the cases of individuals from Hong Kong and Taiwan who especially feared the PRC’s Communist government. Such changes in immigration policy allowed for the pace of Chinese immigration to the United States to further quicken and thus diversified the Chinese food offerings available in NYC’s Chinatowns. Additionally, U.S. President Richard Nixon’s opening of diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China in 1972, helped to further accelerate this second wave of Chinese immigration to United States while creating a renaissance for authentic Chinese food in large U.S. cities such as NYC[6].

Chinese immigrants who came from Taiwan to NYC in the 1970s were predominately middle-class and for this reason they did not fit in with the largely working-class Cantonese inhabitants of Manhattan Chinatown. As a result, the Taiwanese immigrants chose to establish a middle-class Mandarin-speaking Chinatown in Flushing, Queens, NY. Upon coming to the United States, Taiwanese people brought noodle dishes such as Taiwanese beef noodle soup (pictured, Exhibit D) to New York, thus further influencing NYC’s culinary fabric. (Notably, this noodle soup dish was first created by the Hui Muslim minority, who also created Lanzhou’s famous beef noodle soup with hand-pulled noodles). At the same time as these new Taiwanese immigrants, wealthier Chinese immigrants from Hong Kong began coming to the United States as well. Their arrival led to a linguistic and culinary shift in Manhattan’s Chinatown towards different types of Cantonese Chinese noodle dishes in Chinatown beyond Chow Mein, including Hong Kong Crispy Seafood Noodles (pictured, Exhibit E).

Following the Nixon Administration’s easing of diplomatic ties with China, many more wealthy and highly educated Chinese came to the United States, particularly so after the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976. When these new immigrants started coming to the US, they brought their traditional foods with them. As examples, Sichuan and Hunan cuisines appeared in the United States during this time period and noodle dishes such as Sichuan’s dandan mian (Exhibit F) eventually became a staple food of Chinese Sichuan restaurants in NYC. Additionally, Chinese immigrants from large cities such as Shanghai also brought their own regional cuisines with them to New York City, which included noodle dishes such as Chinese Oil Noodles with Scallions, or Cong You Ban Mian (Exhibit G).

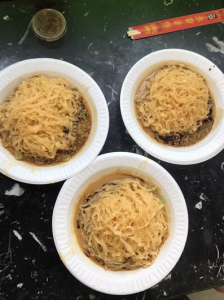

The third concentrated wave of Chinese immigration occurred in the 1980s and 1990s and consisted of poor Chinese immigrants from Fujian Province, many of whom came via illegal means. Since these new Fujianese immigrants did not speak Cantonese (and hence did not fit in culturally with the Cantonese residents of Manhattan’s Chinatown), many of them found themselves settling on the Eastern periphery of Chinatown in the East Broadway area. Chinese immigrants from Fujian brought with them different types of noodles that had not previously been available in the United States, such as ban mian, a cold noodle dish consisting of wheat noodles in a sauce made of soy sauce and peanut butter, the latter being a highly unusual ingredient in Chinese cuisine (pictured, Exhibit H). Although Guangdong and Fujian are located next to each other, the types of noodles dishes that Fujianese immigrants brought to NYC were extremely different from their Cantonese counterparts. Fujianese immigrants later began moving to Sunset Park, Brooklyn in the early 2000s, which before had originally been established as a Cantonese ethnic enclave. Other types of Chinese immigrants who later moved to Sunset Park have included some people from Yunnan in more recent years, as evidenced by the establishment of a Yunnanese restaurant in this neighborhood called “Yun Nan Flavor Garden” (Exhibit I).

Comprising the currently continuing fourth wave of Chinese immigration to the US are a larger number of Mandarin-speaking Northern Chinese people who are currently entering into NYC through both legal and illegal means. According to a 2016 article in NPR titled “Leaving China’s North, Immigrants Redefine Chinese In New York,” NYC’s Chinatowns are becoming increasingly Mandarin-speaking. Because the Southern parts of China have become more economically developed than the Northern ones, much of today’s Chinese immigration stems from Northern cities[7]. Noodle dishes they have introduced include zhajiangmian from Beijing, Xinjiang da pan ji with latiaomian, hand-pulled noodles from Lanzhou, and knife-cut noodles from Xi’an, Shaanxi, China, a Northern-Central region of China. In particular, noodles from Xi’an, Shaanxi have taken New York City by storm over the last decade through the advent of Xi’an Famous Foods, a now 13-restaurant chain that began as a single underground stall in Flushing’s Golden Mall food court in late 2005.

From chow mein to Shaanxi noodles, Chinese noodles have emerged in NYC alongside these four major waves of immigration, and they have also further evolved in response to changing consumer preferences. In recent years, increased accessibility to ethnic foods and consumers’ growing desire for authentic ethnic dining experiences has driven the commercialization of authentic Chinese noodles across NYC. Xi’an Famous Foods is a fine illustration of this development: Through the growth of Xi’an Famous Foods, we can see how the Chinese noodle landscape has changed in NYC as a result of these trends. The restaurant chain’s success has stemmed not only from offering a high quality product that was different from anything else in NYC, but also from the fact that the restaurant’s young owner, Jason Wang, has been able to effectively leverage social media marketing to grow awareness and demand for the chain.

Xi’an Famous Foods specializes in Shaanxi cuisine from the city of Xi’an in Western China. The flavors of Shaanxi cuisine are sour, spicy, and salty. During an interview about Chinese noodles in NYC, Dawn Hu, a now 55-year old Chinese immigrant from Beijing who came to the United States 35 years ago, mentioned that she would never have expected Shaanxi cuisine to arrive in the US, nor for such a restaurant to become a prominent citywide chain[8]. Much of the appeal and growing popularity of Chinese noodles in NYC is from the experience that comes with eating them. “You’re not going to see any of this in Chinatown in Manhattan or in Brooklyn. This is a Queens thing”, according to David Shi, owner of the original Xi’an Famous Foods, Flushing, Queens, NY, when he was interviewed by the recently-deceased globetrotting Travel Channel food critic Anthony Bourdain in 2009.

Before Bourdain paid a visit to Xi’an Famous Foods in Flushing’s Golden Mall during his tour of Queens, NY in 2008, Zhang Meijie, a now 61-year old Chinese woman from Shandong who came to the United States in 1997, had never seen a white person inside the Golden Mall. In a recent interview, Zhang told me that she has lived in Forest Hills, Queens, for 21 years with 12 other members of her family. She told me that she visits the Golden Mall “sometimes” for “chi de dong xi” (things to eat). The first time Zhang saw a white person in the Golden Mall was eight years ago, and since that time she has noticed that white people have started going to the Golden Mall much more often. Zhang told me that she thought it was natural that Westerners wanted to explore the Chinese food scene because they want to experience new tastes, and for this reason she was not surprised to see them there. As of three years ago there have been even more white people coming to Flushing, from her perspective[9]. While the Golden Mall might not seem like the most likely eatery pick for a Westerner (it’s subterranean, dirty by Western standards, and impossible to find unless you speak Chinese or you’re particularly in the know), Anthony Bourdain did much to glamorize the practice of urban ethnic food exploration through his highly popular Travel Channel show No Reservations. Xi’an Famous Foods was arguably one of the largest beneficiaries of Bourdain’s show.

Xi’an Famous Foods’ menu consists mostly of noodle dishes that are sour and spicy in taste, two elements that are not necessarily common in typical American cuisine. For example, noodle dishes at Xi’an Famous Foods such as the “Spicy Cumin Lamb Noodles” (孜然羊肉干扯面; Zī rán yángròu gān chě miàn) that I ate at Xi’an Famous Foods’ Manhattan Chinatown location contain large amounts of bright red chili oil, an ingredient not found in American food (pictured, Exhibit J). True to what the owner Jason Wang said, the restaurant added Sichuan peppercorns to the chili oil, creating a spicy and numbing effect. As someone who is half-Chinese (but not Western Chinese), I would not have personally expected the flavors within that noodle dish to be popular with those who are unacquainted, yet the taste was strangely addictive. Having also tried other menu items at Xi’an Famous Foods at four different NYC locations over the course of two years (Manhattan Chinatown, Flushing original in the Golden Mall (now closed), Upper West Side, and Upper East Side), it is notable that the flavors of the menu items that Xi’an Famous Foods sells are consistent across each branch: Other than asking patrons if they’d like to withhold chili oil for some dishes, no accommodations are made by Xi’an Famous Foods for their dishes to better suit the Western palate.

In a YouTube video on Xi’an Famous Foods that was published by Business Insider, Andrew Coe, a Chinese food historian, remarks that “generations of Chinese restauranteurs” used to make their food “bland to American tastes” when they chose to expand outside of Chinatowns. Owner Jason Wang agreed with Coe’s comment, remarking that “the timing [was] right” for Chinese restaurants like Xi’an Famous Foods to showcase their authenticity instead of watering down their flavors to better align with the American palate. In the same YouTube video, Wang also mentions how his restaurant also chose to add Sichuan peppercorns to some of its dishes, which are not used in traditional Western cuisines and also have a mouth-numbing effect (called mala in Chinese)[10]. While the use of ingredients such as Sichuan peppercorns attest to how much of a radical departure Xi’an Famous Foods’ Chinese dishes are from Western culinary norms, it was precisely these elements of difference within Xi’an Famous Foods’ menu items that helped to propel the business to its current level of success (now a thriving chain of 13 stores spread across the three boroughs of Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn)[11].

On Saturday, June 30th, 2018, Jason Wang opened Xi’an Famous Foods’ 13th store in the West Village, near West 4th Street. According to the real estate sales website Streeteasy.com, the West Village is “the perfect neighborhood for people who like the finer things in life – think lovely window boxes, well-curated bookshops and sophisticated company – but without the fuss or ostentation.[12]” The mere presence of Xi’an Famous Foods in a neighborhood such as the West Village defies all expectations of where a Chinese restaurant of that nature might be placed and highlights the significant extent to which American views on ethnic foods have evolved since the days of chow mein’s emergence in Manhattan Chinatown. To take advantage of word of mouth and social media marketing, Wang ran a promotion offering a free dish to each person who came to the new storefront on opening day and showed on their smartphone that they shared a promotional post about the new Xi’an Famous Foods location’s opening.

Well over a hundred years ago, on Nov 15, 1903, The New York Times ran an article called “Chop Suey Resorts: Chinese Dish Now Served in Many Parts of the City” that detailed the emergence of a new type of Chinese food called chop suey in Chinatown, as well as the customs surrounding the ordering of the dish. While chop suey was fundamentally different from Western foods, the author of the piece wrote that “A dish of chop suey is as digestible again as a broiled lobster or a welsh rabbit,” and this example showcases the role that print media played in helping to spread awareness and acceptability of Chinese ethnic cuisine nearly since it first arrived in NYC[13]. While dishes such as Shaanxi noodles, chop suey, chow mein, and others aforementioned were brought to the NYC area by immigrants, it was changing social sentiment and growing audiences for these foods that influenced their composition and geographic spread. Hence, the Chinese noodle narrative of NYC with regards to the types of noodle dishes available both past and present has evolved throughout history as shaped both by the successive waves of Chinese immigrants settling across the city, as well as the evolving preferences of discerning New York eaters.

Additional Works Consulted:

Lin, Jan. “Reconstructing Chinatown: Ethnic Enclave, Global Change.” Vol. 2 Edition: NED – New Edition (1998).

Kenneth J. Guest. ”From Mott Street to East Broadway: Fuzhounese Immigrants and the Revitalization of New York’s Chinatown.” Journal of Chinese Overseas. Vol. 7 No. 2. Liu Hong and Zhou Min. Singapore: Brill, 2011. 24-44.

Rude, Emelyn. “Chinese Food in America: A Very Brief History.” Time, Time, 8 Feb. 2016.

Liu, Haiming, and Huping Ling. “From Canton Restaurant to Panda Express: A History of Chinese Food in the United States.” Rutgers University Press, 2015. JSTOR.

Staff, Eater. “The Making of Manhattan’s Chinatown | MOFAD City.” Eater, Eater, 17 Aug. 2016.

“Menu.” The Macaulay Messenger, The Arts in New York City, macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/beemanneighborhoods/timelinehistory/.

Business Insider. “How a Son Turned His Dad’s Food Stall into the No. 2 Chinese Restaurant in the US.” YouTube, YouTube, 5 Feb. 2016

“Feature: Chinese Immigration.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service”.

Zong, Jie, et al. “Chinese Immigrants in the United States.” Migrationpolicy.org, 13 June 2018.

“Chinese Immigration and the Transcontinental Railroad.” US Citizenship, www.uscitizenship.info/Chinese-immigration-and-the-Transcontinental-railroad/.

Society, Eric Fish Asia. “How Chinese Food Got Hip in America.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 9 Mar. 2016.

Staff, Eater. “The Ultimate New York City Chinese Food Glossary.” Eater NY, Eater NY, 1 Nov. 2011, ny.eater.com/2011/11/1/6645205/the-ultimate-new-york-city-chinese-food-glossary.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Taiping Rebellion.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 25 July 2017, www.britannica.com/event/Taiping-Rebellion.

Footnotes from Paper:

[1] Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). “Results.” American FactFinder, 5 Oct. 2010, factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_DP05.

[2] Informational Footnote: The Taiping Rebellion was a peasant rebellion in Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces against the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty that took place from 1850-1864.

[3] Hsiung, Deh-Ta & Simonds, Nina (2005). Food of China. Murdoch Books. p. 239.

[4] “Chow Mein, an American Classic.” Appetite for China, 17 July 2009.

[5] “U.S. Immigration Legislation: 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act (Hart-Cellar Act).” U.S. Immigration Legislation: 1940 Naturalization Act.

[6] Rude, Emelyn. “Chinese Food in America: A Very Brief History.” Time, Time, 8 Feb. 2016, time.com/4211871/chinese-food-history/.

[7] Wang, Hansi Lo. “Leaving China’s North, Immigrants Redefine Chinese In New York.” NPR, NPR, 26 Jan. 2016.

[8] Interview with Dawn Hu. Conducted 6/24/18.

[9] Interview with Zhang Meijie. Conducted on 6/28/18.

[10] https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=3C3nz108IIU

[11] “Xi’an Famous Foods Website.” Xi’an Famous Foods, www.xianfoods.com/.

[12] “At A Glace: West Village.” Streeteasy.com, streeteasy.com/neighborhoods/west-village/.

[13] “Chop Suey Resorts: Chinese Dish Now Served in Many Parts of the City.” New York City Chinatown > Newspaper Articles, nychinatown.org/articles/nytimes19031115.html.

Evolution of Chinese Noodles in NYC: A Tale of Immigration and Adaptation – Exhibition

Exhibit A: Map of New York City’s five boroughs. NYC’s three main Chinatowns are outlined.

Exhibit B: Beef Chow Mien at Big Wong Cantonese Restaurant (Photo Credit: Danielle K./Yelp)

Exhibit C: Clay Pot Pearl Noodles Soup煲汤珍珠面条汤 Bāotāng zhēnzhū miàntiáo tang at Nyonya in Manhattan Chinatown

Exhibit D: Taiwanese Beef Noodle Soup 台湾牛肉汤面 Táiwān niúròu tāngmiàn at Taiwan Pork Chop House in Manhattan Chinatown (Source: Eric J./Yelp)

Exhibit E: Hong Kong Crispy Seafood Noodles 香港脆皮海鲜面 Xiānggǎng cuì pí hǎixiān miàn at Nyonya in Manhattan Chinatown.

Exhibit F: Sichuanese Dan Dan Noodles from Chengdu Heaven in Flushing, Queens, NY (Photo Credit: LY L./Yelp).

Exhibit G: Wheat Noodles with Peanut Butter Sauce (拌面; Mixed Noodles) at Shu Jiao Fuzhou Cuisine Restaurant on 118 Eldridge St, New York, NY 10002 (Photo Credit: Anna C./Yelp).

Exhibit H: Shanghainese Oil and Scallion Cold Noodles葱油拌面Cong You Ban Mian at 456 Shanghai Cuisine in Manhattan Chinatown (Nina C./Yelp).

![]()

Exhibit I: Yun Nan Flavor Garden’s #11: Rice Noodles w/Crispy Meat Sauce (Source: Hui Meen O./Yelp) Sunset Park, Chinatown, Brooklyn.

Exhibit J: Xi’an Famous Foods’ “N1: Spicy Cumin Lamb Noodles” 孜然羊肉干扯面 Zī rán yángròu gān chě miàn at the Bayard Street location of the restaurant mini-chain in Manhattan Chinatown, New York, NY.