Shakespeare Syllabus Fall 2021 REV

As a classroom community, our capacity to generate excitement is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence.

―

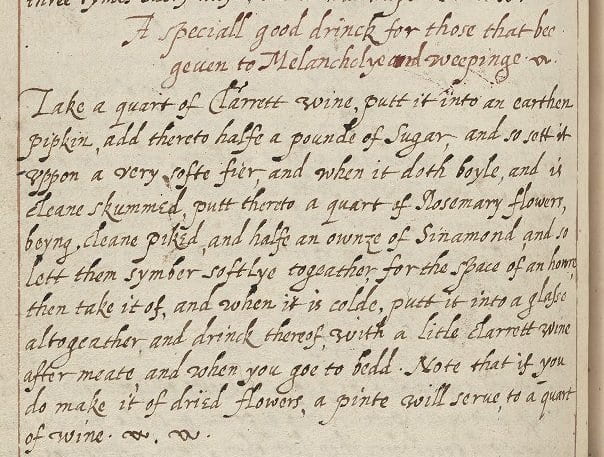

Wholesome Advice Against the Abuse of Hot Liquors

1609 Shake-speares sonnets images, Folger Shakespeare Library

1

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’st flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content

And, tender churl, makest waste in misering.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

3

Look in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime:

So thou through windows of thine age shall see

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

But if thou live, remember’d not to be,

Die single, and thine image dies with thee.

18

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

20

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion;

A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change as is false women’s fashion;

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

A man in hue, all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created,

Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she pricked thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

73

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed whereon it must expire,

Consum’d with that which it was nourish’d by.

This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

116

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand’ring bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me prov’d,

I never writ, nor no man ever lov’d.

138

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue:

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed.

But wherefore says she not she is unjust?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

Oh, love’s best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love loves not to have years told.

Therefore I lie with her and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flattered be.

Differences between quarto and folio

King Lear Under COVID-19 Lockdown

Here’s a clear and helpful guide on how to quote Shakespeare.

And here’s the same professor’s clear guide on quoting prose.

Samuel Johnson, 1765

For the first Shakespeare has suffered the virtue of Cordelia to perish in a just cause contrary to the natural ideas of justice, to the hope of the reader, and, what is yet more strange, to the faith of chronicles….

A play in which the wicked prosper, and the virtuous miscarry, may doubtless be good, because it is a just representation of the common events of human life: but since all reasonable beings naturally love justice, I cannot easily be persuaded, that the observation of justice makes a play worse; or, that if other excellencies are equal, the audience will not always rise better pleased from the final triumph of persecuted virtue….

In the present case the publick has decided. Cordelia, from the time of Tate, has always retired with victory and felicity. And, if my sensations could add any thing to the general suffrage, I might relate, that I was many years ago so shocked by Cordelia’s death, that I know not whether I ever endured to read again the last scenes of the play till I undertook to revise them as an editor.

The Plays of William Shakespeare, ed. Samuel Johnson, London, 1765, p. 207.

August Wilhelm Schlegel, 1835

The story of Lear and his daughters was left by Shakespeare exactly as he found it in a fabulous tradition, with all the features characteristical of the simplicity of old times. But in that tradition there is not the slightest trace of the story of Gloster and his sons, which was derived by Shakespeare from another source. The incorporation of the two stories has been censured as destructive of the unity of action. But whatever contributes to the intrigue or the denouement must always possess unity. And with what ingenuity and skill are the two main parts of the composition dovetailed into one another! The pity felt by Gloster for the fate of Lear becomes the means which enables his son Edmund to effect his complete destruction, and affords the outcast Edgar an opportunity of being the saviour of his father. On the other hand, Edmund is active in the cause of Regan and Goneril; and the criminal passion which they both entertain for him induces them to execute justice on each other and on themselves. The laws of the drama have therefore been sufficiently complied with; but that is the least; it is the very combination which constitutes the sublime beauty of the work. The two cases resemble each other in the main: an infatuated father is blind towards his well-disposed child, and the unnatural children, whom he prefers, requite him by the ruin of all his happiness. But all the circumstances are so different, that these stories, while they each make a correspondent impression on the heart, form a complete contrast for the imagination. Were Lear alone to suffer from his daughters, the impression would be limited to the powerful compassion felt by us for his private misfortune. But two such unheard-of examples taking place at the same time have the appearance of a great commotion in the moral world: the picture becomes gigantic, and fills us with such alarm as we should entertain at the idea that the heavenly bodies might one day fall fro their appointed orbits.

The Romantics on Shakespeare, ed. Jonathan Bate, Penguin, 1997, p. 383.

Jonathan Dollimore, 2004

King Lear is, above all, a play about power, property, and inheritance.

Radical Tragedy: Religion, Ideology, and Power in the Drama of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries, Jonathan Dollimore, Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1999, p. 190.

First drafts and perfectionism

Humanity does not gradually progress from combat to combat until it arrives at universal reciprocity, where the rule of law finally replaces warfare; humanity installs each of its violences in a system of rules and thus proceeds from domination to domination” (Foucault, 1984).

Measure for Measure with Romola Garai

Premieres Friday, October 19 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings)

Streams Saturday, October 20 at pbs.org/shakespeareuncovered and on PBS appsMeasure for Measure takes an astonishingly timely look at sexual morality, hypocrisy and harassment. Shakespeare asks us to “measure” the price of liberty against the moral and social cost of libertinism. It’s a play about vice, the law and sexual corruption at the highest levels and, for nearly two centuries, it was considered too racy to be produced on the English stage. Garai explains why there is no light-hearted happy ending in this play, but something much darker and more complex — truly a sexual tale for our time.

Durer, c. 1526:

“In sooth I know not why I am so sad”

“In Belmont is a lady richly left”

“If thou keep promise, I shall end this strife / Become a Christian and thy loving wife”

“The villany you teach me I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction”

“The Duke shall grant me justice”