Contributed by Chantele Collings-Faulkner

We’re all going to die!!!! Right? Yes, but not necessarily from Ebola!

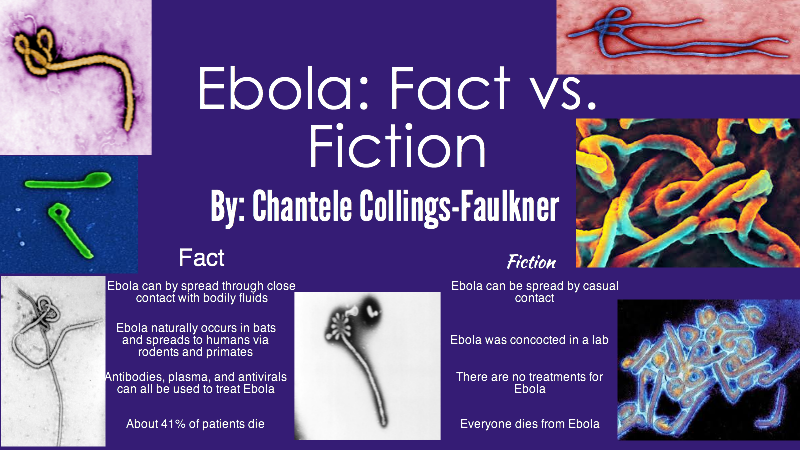

Much of what is thought to be true about Ebola is actually wrong.

The genus Ebolavirus consists of five different variants of a single stranded RNA virus that originate from many parts of Africa. Though previous outbreaks have occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Olabode 2015), the most recent outbreak of Zaire ebolavirus began in Guinea and spread to Sierra Leone and Mali (Park et al 2015 and Carroll 2015). Though a series of zoonotic introductions to the human population was initially suspected to be the cause of the rapid spread of the disease, Park and colleagues determined that human to human transmission was the greatest cause of the expansion of the epidemic into Sierra Leona as the Ebola viruses shared common ancestors with a particular strain from Guinea (Park et al 2015 and Caroll 2015).

At the time, some feared the spread of Ebola to America because of the depth of interconnection between countries. However, Ebola does not spread that easily in the initial, well stages. It requires near death-bed symptoms, where caregivers are involved with caring for the sick patient. These close relatives and healthcare workers are at the greatest risk for contracting the disease, as it is spread through bodily fluids, not simple, casual contact. Symptoms of severe disease include bloody diarrhea, bloody vomiting, and bleeding through eyes, nose, mouth, and anus. Very effectively, the virus uses such fluid means to spread from person to person during care or burial, infecting others in close proximity to the patient.

Though there is no current vaccine (several are being developed), treatments include rehydration, monoclonal antibody infusion, plasma donation from survivors, and antiviral therapy called ZMapp, which has shown to be very effective in treating the disease. The Ebola virus also has not been changing genetically in the past 40 years, which offers hope for a cure (Baize 2015, Kugleman 2015, and Liu 2015). Prevention involves bleach solutions and strict adherence to PPE (personal protective equipment) guidelines to minimize exposure and reduce disease transmission.

To learn more:

Azarian, Taj, et al. 2015. Impact of spatial dispersion, evolution, and selection on Ebola Zaire Virus epidemic waves. Scientific Reports 5: 10170.

Baize, S. (2010). Towards broad protection against ebolaviruses. Future Microbiology 5: 1469-73.

Caroll, Miles W., et al. 2015. Temporal and spatial analysis of the 2014–2015 Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa. Nature 524: 97–101.

Kiran, Narasinha Mahale, Milind S. Patole. 2015. The crux and crust of ebolavirus: Analysis of genome sequences and glycoprotein gene. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 463: 756–761.

Kugelman, Jeffrey R., et al. 2015. Monitoring of Ebola Virus Makona Evolution through Establishment of Advanced Genomic Capability in Liberia. Emerging Infectious Disease 21: 7.

Liu, Si-Qing, et al. 2015. Identifying the pattern of molecular evolution for Zaire ebolavirus in the 2014 outbreak in West Africa. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 32: 51–59.

Olabode, Abayomi S., et. al. 2015. Ebolavirus is evolving but not changing: No evidence for functional change in EBOV from 1976 to the 2014 outbreak. Virology 482: 202–207.

Park, Daniel J., et al. 2015. Ebola Virus Epidemiology, Transmission, and Evolution during Seven Months in Sierra Leone. Cell 161: 1516–1526.