Weingart S, et al. “Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management.” Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:165-175.

Clinical question / background:

· Patients requiring emergency airway management are at great risk of hypoxemic hypoxia because of primary lung pathology, high metabolic demands, anemia, insufficient respiratory drive, and inability to protect their airway against aspiration. Tracheal intubation is often required before the complete information needed to assess the risk of periprocedural hypoxia is acquired. Desaturation to below SpO2 70% puts patients at risk of arrhythmia, hemodynamic decompensation, hypoxic brain injury and death. This paper reviews the research and makes recommendations for preoxygenation before intubation in the Emergency Department

Sequence of Preoxygenation and Prevention of Desaturation

Preoxygenation Period

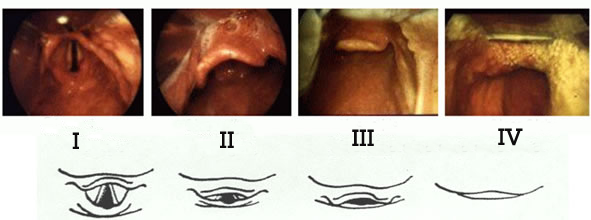

· Position the patient in a semi-recumbent position or in reverse Trendelenberg. Position the patient’s head in the ear-to-sternal-notch position using padding if necessary.

· Place a nasal cannula in the patient’s nares. Do not hook the nasal cannula to oxygen regulator.

· Place patient on a non-rebreather mask at the maximal flow allowed by the oxygen regulator (at least 15lpm, but many allow a much greater uncalibrated flow)

· If patient is not saturating >90%, remove face mask and switch to non-invasive CPAP by using ventilator, non-invasive ventilation machine, commercial CPAP device, or BVM with PEEP valve attached. Titrate between 5-15cm H2O of PEEP to achieve an oxygen Saturday >98%. Consider this step in patients saturation 91-95%.

· Allow patient to breath at tidal volume for 3 minutes or ask the patient to perform 8 maximal exhalations and inhalations.

Apneic Period

· Push sedative and paralytic (Preferably rocuronium, if the patient is at risk for rapid desaturation)

· Detach face mask from the oxygen regulator and attach the nasal cannula. Drop the flow rate to 15lpm.

· Remove the face mask from the patient

· Perform a jaw thrust to maintain pharyngeal patency

· If the patient is high risk (required CPAP for preoxygenation), consider leaving on the CPAP during the apneic period or providing 4-6 ventilations with the BVM with a PEEP valve attached. Maintain a two-hand mask seal during the entire apneic period to maintain the CPAP

Intubation Period

· Leave the nasal cannula on throughout the management period to maintain apneic oxygenation